Background Paper No. 35

BY Udaibir DAS* and hansika Nath

SUMMARY

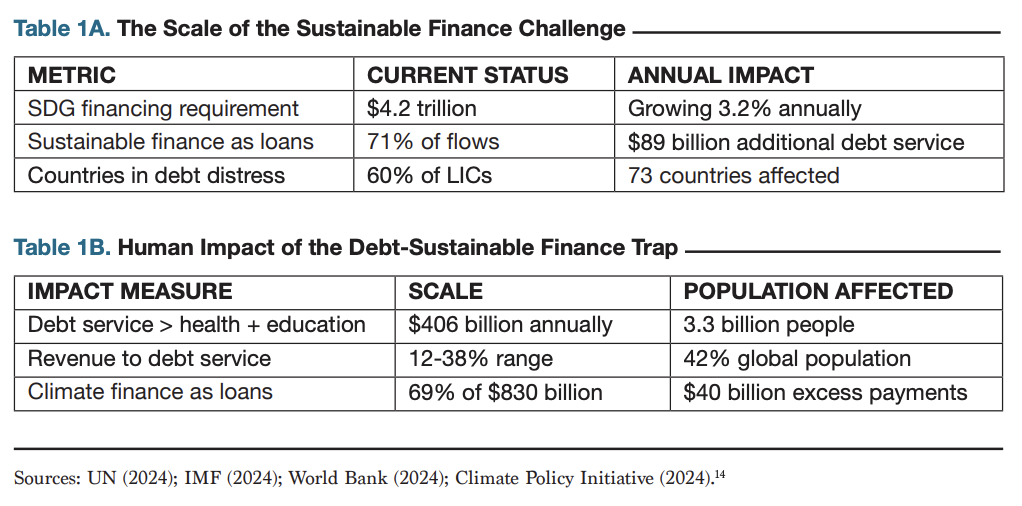

Sustainable development finance is trapped in a structural bind: the needs are rising, but the instruments are skewed toward debt. Developing economies must mobilize an estimated $4.2 trillion annually to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and climate targets, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Simultaneously, over two-thirds of public climate finance for transitions provided by developed countries to developing countries is extended as loans rather than grants, thereby reinforcing debt burdens. Meanwhile, approximately 3.3 billion people reside in countries that allocate more funds to debt service than to either education or health, indicating that debt service already supplants core development spending.

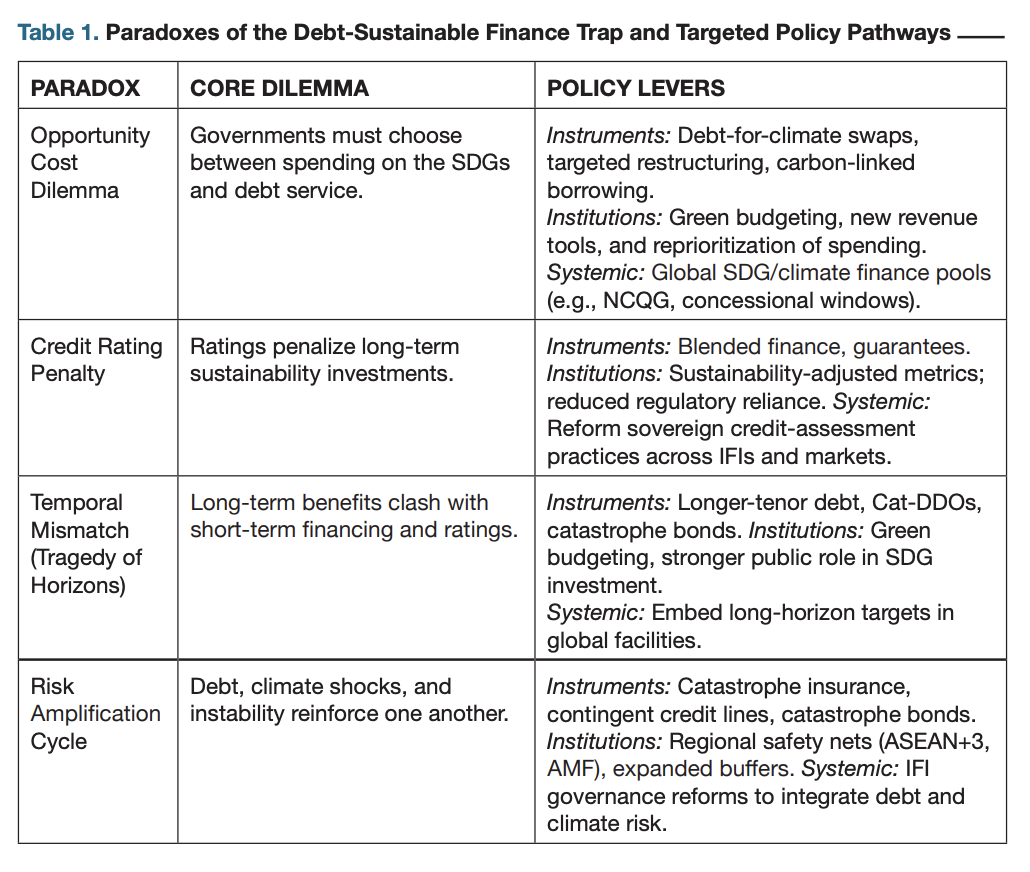

Standard prescriptions, such as sequencing reforms, blended finance, and capacity building - do not address the paradoxes at the heart of today’s debt-sustainability nexus. This paper identifies four such paradoxes: the opportunity-cost dilemma, the credit-rating penalty, the temporal mismatch (Mark Carney’s “Tragedy of Horizons”), and the risk-amplification cycle. Country experiences, from debt-distressed economies in Africa and Latin America to large emerging markets like India, reveal consistent patterns: national initiatives can ease pressures, but systemic paradoxes persist.

These paradoxes translate into concrete financing constraints that governments face daily. The table below distills each paradox into its core dilemma and highlights policy levers at the instrument, institutional, and systemic levels.

I. INTRODUCTION

The contemporary development finance landscape embodies a fundamental contradiction. Countries must invest substantially in renewable energy, climate adaptation, health systems, and education to achieve the SDGs. However, the predominant financing mechanisms available often transform these essential investments into unsustainable debt burdens. This creates what can be termed a “debt-sustainable finance trap” wherein the pursuit of sustainability goals through available financial instruments directly undermines fiscal stability.

Unlike previous debt crises attributed to fiscal mismanagement or external shocks, the current predicament emerges from structural features of the sustainable finance system itself. Countries implementing sound macroeconomic policies and investing in productive green infrastructure still face deteriorating debt dynamics because sustainable finance available for these purposes arrives predominantly in the form of loans rather than grants. When climate finance, ostensibly designed to address a crisis that developing countries did not create, arrives 61 percent in loan form, the arithmetic contradiction becomes clear.

The human dimensions of this trap prove particularly severe. In 2023, developing countries allocated $406 billion to debt service, resources sufficient to provide universal healthcare for 2.1 billion people or fund climate adaptation for 400 million vulnerable citizens. This represents not merely inefficient resource allocation, but a systematic denial of sustainable development opportunities mandated by the SDGs and the Paris Agreement.

For purposes of this analysis, debt encompasses all financial obligations requiring repayment with interest, including: (a) bilateral loans from government agencies; (b) multilateral loans from development banks and climate funds; (c) commercial loans from private banks; (d) sovereign bonds held by private and institutional investors; (e) green/climate/ SDG bonds that, despite their labeling, remain debt instruments; (f) non-concessional lending regardless of purpose. This excludes equity investments, grants, and highly concessional financing with grant elements exceeding 35 percent as calculated by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) methodology.

Sustainable finance refers to capital flows explicitly directed toward achieving the SDGs and Paris Agreement objectives, including: (a) climate finance for mitigation and adaptation (renewable energy, resilience infrastructure, nature-based solutions); (b) SDG financing for health, education, water, sanitation, and poverty reduction; (c) green/blue/ social/sustainability bonds and loans; (d) biodiversity and ecosystem financing; (e) just transition investments. Critically, these flows are examined by instrument type (grant vs. loan) rather than by label, as most “sustainable finance” arrives in the form of debt, despite its developmental purpose, creating the trap analyzed herein. The OECD estimates only 29 percent of sustainable finance arrives as grants, with 71 percent creating debt obligations regardless of the sustainable label attached.

This analysis draws on multiple datasets and institutional sources to establish the quantitative foundation for the debt-sustainable finance trap framework. Key data sources include: (1) Debt and fiscal data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook Database, World Bank International Debt Statistics, and country specific debt sustainability analyses; (2) Climate finance flows from Climate Policy Initiative Global Landscape reports (2022-2024), Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development - Development Assistance Committee (OECD DAC) statistics, and multilateral development bank annual reports; (3) SDG financing gaps from United Nations (UN) Financing for Sustainable Development Reports and country-specific assessments; (4) Credit spreads and risk premiums from sovereign bond yield data and country risk assessments.

The sustainable finance composition analysis combines OECD DAC statistics on official development assistance with the Climate Policy Initiative’s tracking of climate finance instruments, covering the period from 2020 to 2023. All monetary figures are in constant 2024 U.S. dollars unless otherwise specified. Country case studies represent different geographic regions, income levels, and debt sustainability profiles while ensuring data availability.

II. UNDERSTANDING THE TRAP: FIVE REINFORCING MECHANISMS

The debt-sustainable finance trap operates through five interconnected mechanisms that create self-reinforcing dynamics, making escape progressively more difficult over time. These are explained below.

The Financing Structure Problem

The fundamental mismatch between the needs of sustainable development and the available instruments creates the foundation of the trap. Sustainable development finance arrives predominantly as debt obligations—71 percent as loans or bonds requiring repayment with compound interest—while only 29 percent arrives as grants. Additionally, about 23 percent of total sustainable finance flows take the form of return seeking private investments. This structure ensures that every investment in renewable energy infrastructure, climate resilience, or SDG achievement immediately worsens debt sustainability metrics, creating a paradox where countries appear least creditworthy when investing most in sustainable transformation (Tables 1A and 1B).

Credit rating agencies deepen this structural problem. Their methodologies do not differentiate between borrowing for long-term, productivity enhancing green projects and borrowing for short-term consumption. An investment in solar infrastructure that cuts import dependence and generates returns over 25 years receives identical treatment to fossil fuel import financing. This is not merely an oversight but a systemic feature: ratings frameworks are designed for short-term fiscal and external balance metrics and therefore structurally penalize investments whose benefits unfold over decades. Countries with the highest SDG financing needs face average rating downgrades of 2.7 notches, translating to additional borrowing costs of 275–400 basis points and roughly $40 billion annually in excess interest payments for climate vulnerable nations.

This misalignment has been highlighted by market analyses such as Moody’s “Climate Change and Sovereign Risk” infographic, which illustrates how climate exposure elevates sovereign risk assessments despite the presence of resilience building investments.

THE OPPORTUNITY COST DILEMMA

Debt service obligations create rigid budget constraints that force governments into increasingly severe trade-offs between creditor payments and sustainable development investments. When debt service commands fixed shares of government revenue through legal covenants and automatic appropriations, SDG-related expenditures necessarily bear the burden of adjustment.

Analysis of budget allocations during crisis periods reveals these tragic choices starkly. Nigeria allocated $4.2 billion to debt service in 2020, while its entire health budget totaled $1.8 billion—a 2.3:1 ratio during a global pandemic. Ecuador faced impossible choices between healthcare and debt service, with the government maintaining bond payments while doctors protested a lack of medical supplies during the pandemic. Pakistan delayed climate adaptation projects following the 2022 floods, which affected 33 million people, to preserve its creditworthiness ratings, as climate vulnerability becomes increasingly expensive to maintain.

THE CREDITWORTHINESS PENALTY

Financial markets systematically penalize countries with the most significant sustainable development financing needs, creating perverse incentives against green investment. This penalty operates through multiple layers that compound upon each other. Countries with per capita incomes below $2,000 face baseline poverty premiums averaging 234 basis points. Climate vulnerability adds 147 basis points for nations with high physical risk exposure. Commodity dependence contributes 89 basis points to economies where extractive industries account for more than 20 percent of exports. Governance assessments impose additional penalties of 112 basis points for countries with institutions of below median strength. These penalties can be considered additive, illustrating how multiple structural vulnerabilities combine to raise financing costs sharply. For example, a country with a low per capita income, high climate vulnerability, commodity dependence, and weak governance could theoretically face a combined creditworthiness penalty of approximately 592 basis points. Zambia offers a real-world illustration: it suffers from all these structural risks, and as of mid-2024, its Eurobond yields have often exceeded 12 percent, reflecting an exceptionally high risk premium compared to global benchmarks. Comparable climate finance costs in debt for renewable projects average about 22.7 percent for Ghana, 29.5 percent for Egypt, 38.1 percent for Sri Lanka, and 54.1 percent for Argentina.

Borrowing cost premiums create self-reinforcing dynamics that undermine sustainable finance. Higher sovereign spreads reduce fiscal space for climate resilience investment by an average of 1.7 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) annually. Lower resilience spending raises vulnerability indices by 0.23 standard deviations per year, and rising vulnerability in turn lifts sovereign CDS spread by 84 basis points. Small island developing states (SIDS) face the most severe constraints: climate exposure sharply limits their access to markets on reasonable terms. Because borrowing costs are closely tied to ratings methodologies that emphasize short-term fiscal metrics, the system penalizes long-horizon sustainability investments. This exemplifies Mark Carney’s “Tragedy of Horizons”: markets discount long-term risks, underinvest in resilience, and force governments into trade-offs between SDG spending and debt repayment.

THE TEMPORAL MISMATCH

Sustainable development investments generate returns over extended time horizons that fundamentally conflict with debt repayment schedules. Infrastructure impact assessments indicate that renewable energy installations achieve economic breakeven after 12.4 years, with full returns realized over a 25–30-year operating life. Educational infrastructure yields its peak economic returns of 32-45 years post-construction, as educated cohorts enter their prime productivity years. Green infrastructure and nature-based solutions generate measurable benefits over 50-75 year time scales through climate mitigation and ecosystem services.

Yet, sustainable finance markets operate on compressed timelines. The average maturity for developing country green bonds is 7.2 years, with 68 percent of sustainable finance instruments maturing within 10 years. This creates an 11.5-year average gap between economic payback and financial maturity, forcing countries to refinance sustainable projects multiple times before they generate positive cash flows. Each refinancing exposes countries to interest rate risk, currency fluctuations, and market access constraints, transforming patient sustainable development needs into urgent liquidity crises.

THE RISK AMPLIFICATION SPIRAL

Climate shocks interact with debt dynamics through feedback loops that amplify vulnerabilities. When disasters strike, sovereign borrowing costs rise by an average of 147 basis points, with the effect persisting for more than three years. Reconstruction requires new borrowing for resilient infrastructure, while destroyed assets continue to demand debt service. Disaster-driven currency depreciation inflates the local currency value of foreign-denominated debt by 21 percent. Over the next five years, renewable energy investment falls by 34 percent and adaptation spending by 23 percent, while debt service remains at 97 percent of pre-disaster levels. The result is a spiral that entrenches divergence: climate vulnerable countries become progressively less able to finance resilience as needs expand.

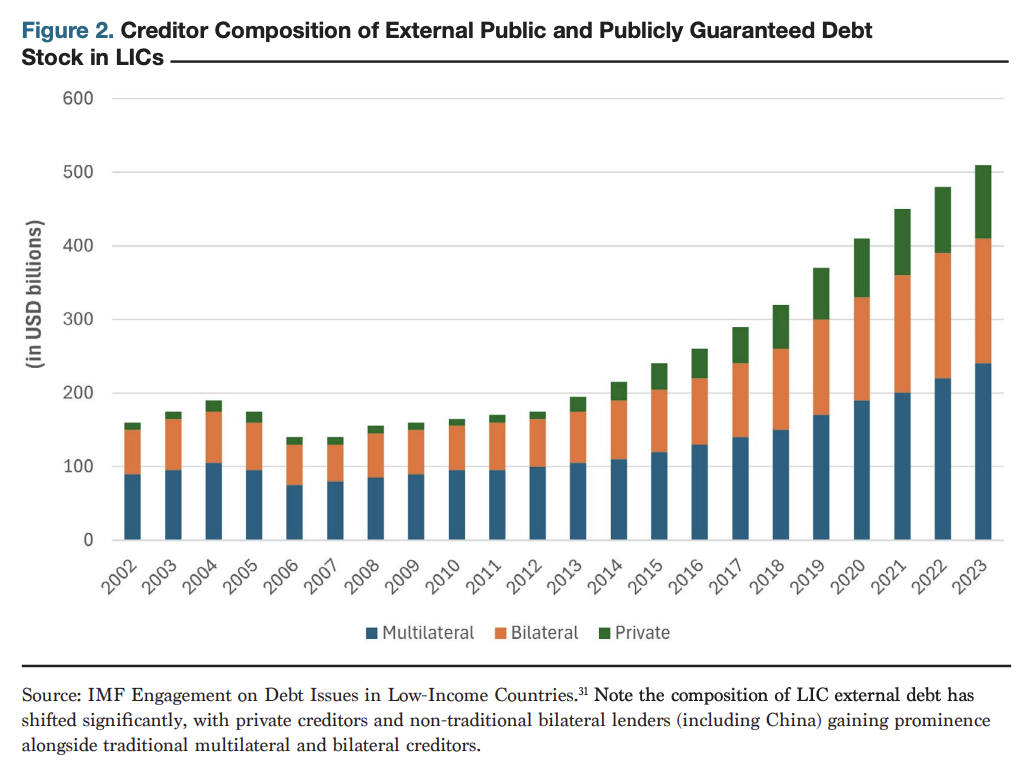

The declining share of multilateral development banks (MDBs) signals a broader shift toward alternative financing sources such as private green bonds and non-concessional bilateral loans, particularly from emerging lenders like China. While these instruments can expand access to capital, they often carry higher costs and shorter maturities, heightening refinancing pressures and fiscal risks for developing countries (as shown in Figure 2).

To navigate this shift, recent guidance emphasizes the importance of sequencing: countries should begin by addressing foundational barriers through concessional finance, targeted policy reforms, and institutional capacity-building. Once these conditions are in place, instruments like China’s green lending and private green bonds can be strategically blended with MDB and bilateral finance. Collaborative, layered approaches anchored in national investment roadmaps, harmonized standards, and strengthened local financial systems offer a more effective pathway to mobilize larger volumes of sustainable climate finance.

III. COUNTRY EXPERIENCES: LESSONS FROM SUSTAINABLE FINANCE ATTEMPTS

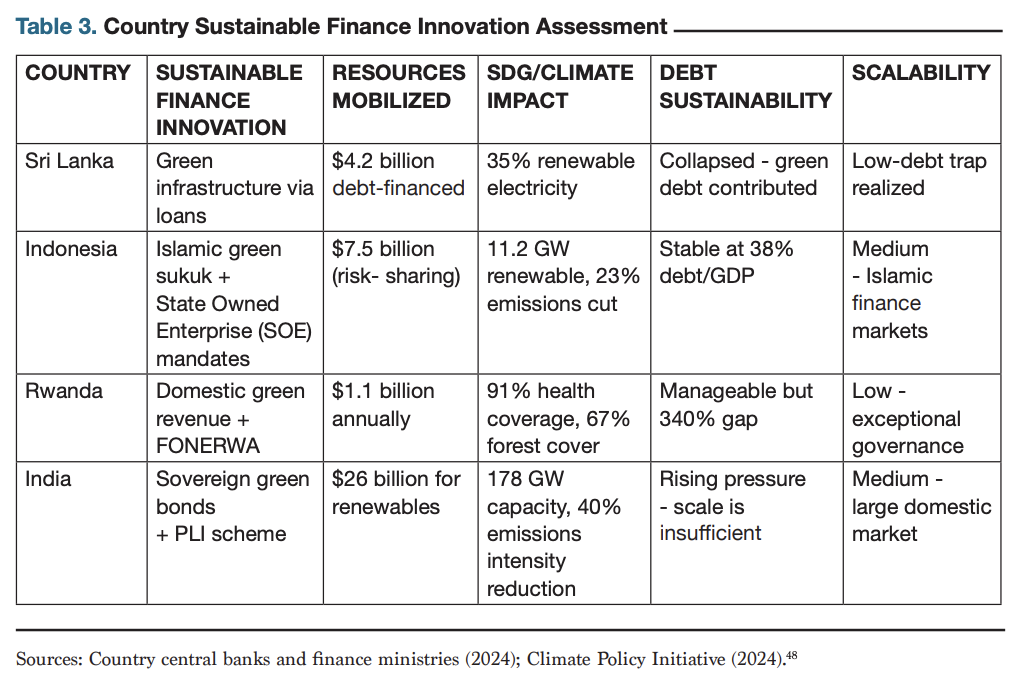

An examination of country experiences reveals both the negative impacts of the trap on sustainable development and the limitations of unilateral attempts to escape it. Below, we describe four country cases – Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Rwanda, and India – to illustrate some of the challenges policymakers face and the lessons that can be drawn from them.

Sri Lanka: When Green Ambitions Meet Debt Reality

Sri Lanka’s economic collapse in 2022 provides a paradigmatic case of how sustainable development ambitions collide with debt arithmetic. The country had invested $4.2 billion in renewable energy infrastructure through international climate loans, achieving 35 percent clean electricity generation and reducing carbon intensity by 23 percent. The government attempted a rapid transformation of its agricultural sector toward organic farming, reflecting genuine sustainability goals aligned with SDG 2 and SDG 13.

However, these green ambitions encountered insurmountable constraints. External debt reached $51 billion, with annual service obligations of $7 billion exceeding total government revenue of $6.7 billion — much of it accumulated through sustainable development borrowing at market rates. The agricultural transformation, implemented without adequate transition financing or support systems, resulted in yield declines of 43 percent in rice production and $425 million in tea export losses.

The ensuing crisis saw inflation reach 73.7 percent, currency depreciation of 81 percent, and economic contraction of 7.8 percent. Despite previous renewable energy investments that should have enhanced creditworthiness by reducing import dependence, debt sustainability assessments treated Sri Lanka identically to countries lacking such sustainable assets. The renewable infrastructure financed through loans became stranded investments under the IMF’s austerity requirements, which prioritized debt service over the green transition. While Sri Lanka illustrates how the financing structure problem and temporal mismatch can create a crisis even with sound green investments, Indonesia’s experience demonstrates how alternative frameworks can open new avenues for sustainable finance.

Indonesia: Islamic Sustainable Finance Innovation

Indonesia demonstrates how alternative financial frameworks can partially circumvent the constraints of conventional sustainable finance. The country has issued $3.5 billion in green sukuk structured as profit-sharing instruments rather than fixed-interest debt. Sukuk are bond-like instruments structured around asset-backed returns rather than conventional interest payments. Under Islamic finance principles, if climate impacts reduce solar farm output or flood damages green infrastructure, investor returns decline proportionally rather than maintaining fixed obligations regardless of project performance.

This risk-sharing structure aligns incentives between sustainable finance providers and the achievement of development outcomes. Real asset requirements in Islamic finance create additional accountability by linking each green sukuk issuance to specific renewable energy projects, including identified solar installations, designated conservation areas, and specific green buildings. This prevents the abstraction that often divorces sustainable finance rhetoric from environmental reality.

Beyond innovative instruments, Indonesia mandates that state-owned enterprises contribute between 2 percent and 4 percent of their profits to national climate and SDG funds, generating approximately $4 billion annually for sustainable investment without external borrowing. Despite adding 11.2 gigawatts (GW) of renewable capacity and achieving 18 percent clean energy generation, debt remains manageable at 38 percent of GDP, demonstrating that alternative sustainable finance pathways exist within arithmetic constraints. Indonesia’s innovations show promise but remain limited by scale. Rwanda’s experience reveals how even exceptional governance and domestic resource mobilization cannot overcome global arithmetic constraints.

Rwanda: Maximizing Domestic Sustainable Finance Capacity

The case of Rwanda demonstrates how robust governance can expand domestically available resources for sustainable development, though even ideal performance cannot escape global mathematic limitations. Tax revenue increased from 10 percent to 16.8 percent of GDP between 2010 and 2024 through systematic reforms explicitly linked to SDG financing. Electronic billing machines deployed in 42,000 businesses reduced value-added tax evasion by 67 percent, with proceeds earmarked for health and education. Digital property registration systems increased property tax collection by 423 percent in real terms, funding urban green infrastructure.

The National Fund for Environment and Climate Change (FONERWA) has demonstrated innovative pooling of sustainable finance resources, combining domestic revenues, carbon credit sales, and international climate finance while maintaining Rwandan ownership. With 60 percent of its $287 million portfolio sourced domestically, the fund reduces dependence on debt-creating climate loans while building institutional capacity for green project management.

Yet the debt sustainability trap binds even Rwanda’s tremendous achievements. Total sustainable development financing needs of 18.7 percentage points of GDP over the coming decade exceed domestic capacity by 340 percent. The climate adaptation gap alone requires $4.1 billion yearly against total government revenues of $2.1 billion. Rwanda maximizes agency within constraints but cannot escape the fundamental mismatch between national resources and global sustainable development imperatives. Rwanda maximizes national agency within constraints, but India’s experience at a massive scale reveals both the potential and ultimate limitations of working within the current sustainable finance architecture.

India: Credit Ratings and the Cost of Scale

India’s sustainable finance experiments show both the scope and the limits of scaling. In January 2023, the government raised US$2 billion through sovereign green bonds, priced just six basis points above comparable government securities, with approximately 85 percent of the bonds purchased by domestic institutional investors. This demonstrated the potential to mobilize local savings without heavy reliance on volatile foreign capital.

The Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme commits $24 billion in budgetary support, not new borrowing, to expand renewable energy manufacturing capacity, reducing import dependence and creating green industrial employment. Solar module output has increased from 2.3 GW in 2014 to 48 GW in 2024, alleviating future current account pressures while enhancing technological capabilities.

India is not in a debt trap: foreign currency debt is relatively low, mostly bilateral or multilateral with long maturities; the current account deficit is manageable; reserves are substantial; and growth is near five percent. India is highlighted here instead for the credit rating distortion it illustrates despite these strengths, the sovereign rating remains at BBB, inflating the external cost of capital for green and other investments.

Yet scale remains the binding constraint. Renewable capacity targets of 178 GW by 2024 and 500 GW by 2030 require cumulative investments of $244 billion and $870 billion, respectively. In contrast, annual sustainable finance flows of only $44 billion fall far short of the estimated $170 billion needed. Green bonds, while useful for market development, add to public debt and require servicing regardless of climate outcomes. This highlights how ratings frameworks and maturity mismatches can constrain ambitions, even in cases where domestic mobilization and industrial policy are strong.

IV. INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE: PROGRESS AND LIMITATIONS IN SUSTAINABLE FINANCE ARCHITECTURE

International institutions have launched multiple initiatives addressing aspects of the debt-sustainable finance nexus. However, none resolve the fundamental contradictions inherent in financing long-term sustainability through short-term debt instruments.

The IMF’s 2024 Debt Sustainability Framework review introduces climate vulnerability assessments and stress testing for transition risks. The new Debt-at-Risk model incorporates macro-financial dangers from climate change and stranded assets, projecting that 47 percent of low-income countries face a high probability of distress under climate stress scenarios. However, the framework maintains a uniform treatment of all debt, regardless of purpose. Climate adaptation loans receive the same sustainability assessment as fossil fuel import financing, thereby perpetuating the lack of attention to sustainable finance quality (Table 3).

The Resilience and Sustainability Trust offers 20-year loans at an interest rate of 1.05 percent for climate and pandemic preparedness, with $40 billion in commitments representing progress in addressing long-term sustainable development challenges. Yet access requires concurrent IMF programs with associated fiscal consolidation measures that often mandate cuts to climate and social spending, limiting uptake to 17 countries that can simultaneously satisfy sustainability investment needs and austerity demands.

The African Development Bank’s (AfDB) Sustainable Borrowing Policy Framework attempts to shift from debt volume to development impact metrics, introducing “green adjusted debt sustainability” measures. Countries demonstrating high ratios of climate and SDG returns to debt service access concessional windows, regardless of income classification. The Room to Run synthetic securitization transferred $4 billion in climate and infrastructure risk to private insurers, freeing equivalent green lending capacity. However, the total AfDB sustainable development lending of $8.9 billion annually represents merely 2.1 percent of Africa’s $424 billion sustainable finance needs.

Several other innovative instruments show promise, but face scalability constraints. Climate-resilient debt clauses, pioneered by Barbados, feature the automatic suspension of payments during defined climate-related disasters, with 12 Caribbean nations adopting this approach, covering $7.2 billion in bonds.

Yet, private creditor resistance limits expansion, with only 31 percent of new sustainable bond issuances. Recent debt-for-nature swaps have achieved a larger scale. However, detailed analysis reveals systematic dual objective failure. Across documented swaps totaling $3.5 billion, average debt relief measures amount to only 0.8 percent of GDP, with transaction costs consuming up to 25 percent of nominal relief while creating sovereignty constraints through offshore control mechanisms. Belize’s $553 million swap for marine protection and Gabon’s $500 million swap for forest conservation stand out as notable examples, yet total swaps since 1987 sum to only $2.6 billion, representing 0.03 percent of developing country debt.

V. BREAKING THE TRAP: NECESSARY TRANSFORMATIONS

Resolution of the debt-sustainability trap requires transformation across multiple dimensions. The needed evolutions include both ongoing debates about optimizing domestic resource mobilization and reform of the international financial architecture.

Domestic Resource Mobilization

Developing countries have a substantial scope for expanding domestic resources, although even maximum mobilization cannot close the gap alone. Tax revenues in developing countries average 15-20 percent of GDP, compared to 34 percent in OECD nations, representing a potential additional annual resource of $1.2 trillion. Digital financial systems enable the formalization of economic activity and the expansion of tax bases. Kenya’s mobile money transaction levy generates approximately $180 million annually to support universal health coverage. Ghana’s digital property addressing system increased collection by 267 percent. India’s goods and services tax integration added 1.8 percentage points to GDP in revenues.

Energy subsidy reallocation offers immediate fiscal space. Developing countries allocated $320 billion to energy subsidies in 2023, with 61 percent of the benefits captured by the wealthiest population quintile. Indonesia’s subsidy reforms freed $15.6 billion for targeted social protection and human development programs. Morocco redirected $2 billion from fuel subsidies to investments in education and health. Natural resource revenue management through sovereign wealth funds can transform volatile commodity income into stable development finance, as demonstrated by Botswana’s Pula Fund, which finances universal primary education and health coverage. These cases show that the key threshold is not just cutting subsidies, but ensuring that at least a few percentage points of GDP are reliably redirected into social and climate investments to build lasting fiscal resilience.

International Financial Architecture Reform

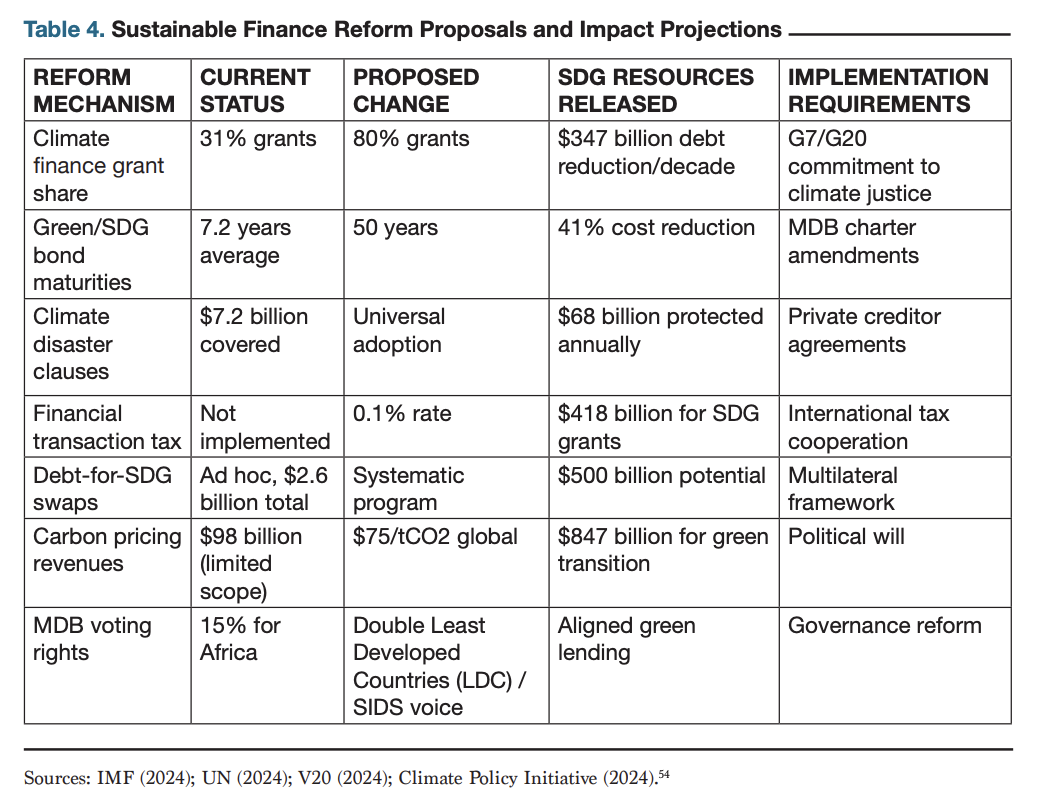

Breaking the trap ultimately requires fundamental reforms to the international financial architecture. Converting climate finance from the current 31 percent grant share to 80 percent would reduce debt accumulation by $347 billion over the next decade, while maintaining investment levels. A financial transaction tax of 0.1 percent in major markets could generate $418 billion annually for grant-based development finance.

Extending development loan maturities from the current 7.2-year averages to 50-year terms would align financing with infrastructure lifecycles. Such maturity extension would reduce refinancing risk by 73 percent. The United Kingdom’s century bonds and Austria’s 100-year issuances demonstrate that market appetite exists for ultra-long maturities when backed by credible institutions.

Automatic stabilization mechanisms must replace discretionary negotiations during crises. State-contingent instruments that adjust payment obligations to economic outcomes would share risks between creditors and debtors. Systematic disaster clauses would preserve $68 billion in fiscal space during climate shocks. GDP-linked bonds would prevent debt spirals during economic contractions.

Governance reform remains essential for legitimacy and effectiveness. Practical steps toward governance reforms — such as doubling the voting shares of developing countries — could be realistically initiated through strategic advocacy within existing institutional forums, including upcoming G20 and G7 summits, IMF-World Bank Annual and Spring Meetings, and specific multilateral reviews like the IMF quota review or World Bank governance restructuring processes. Aligning these changes with ongoing institutional reform dialogues could provide momentum and practical pathways toward achieving these essential governance adjustments. These are summarized in Table 4.

Several limitations should be acknowledged for this analysis. First, measurement challenges exist in defining “sustainable finance,” as classifications vary across institutions. Second, data availability constraints limit the temporal scope for newer instruments, such as green bonds. Third, establishing causal links between sustainable finance structure and debt outcomes is complex, given multiple simultaneous factors. Fourth, country case studies, although diverse, cannot fully capture the heterogeneity of developing country contexts. Finally, dynamic effects of policy reforms may alter identified mechanisms over time. These are areas for further work and research, particularly in terms of scalability measurement and data constraints.

VI. CONCLUSION

The debt-sustainable finance trap is not a conventional crisis that can be fixed at the margin; it is embedded in the architecture itself. The four paradoxes identified in this paper reveal systemic misalignments: short-term financing costs versus long-term development returns; private risk assessments versus public policy priorities; and prevailing rules of creditworthiness versus the realities of climate and SDG investment.

The arithmetic is unforgiving: sustainable development and climate action require about $4.2 trillion annually, yet tracked flows remain below $830 billion, with roughly 70 percent arriving as debt rather than grants. Developing countries face borrowing costs 275-400 basis points above advanced-economy benchmarks; at the end of 2023, emerging-market hard-currency spreads still averaged 380 basis points over U.S. Treasuries.

National initiatives can ease pressures but cannot overturn these arithmetic constraints. Approximately 3.3 billion people reside in countries where the amount spent on interest exceeds the combined amount spent on education and health. Debt-for-nature swaps illustrate the structural limits: they have reduced less than 0.03 percent of developing-country obligations in 35 years, generating far smaller relief than the Brady Plan of the late 1980s, which delivered an average of 35 percent debt reduction. Even the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust, at $40 billion, equals barely 10 percent of annual debt service payments in developing economies. Incremental tools provide symbolic gains, but without systemic change, the paradoxes remain binding.

Time compounds the urgency. Each year of delay adds roughly $406 billion in debt service obligations, reduces sustainable development spending by $237 billion, and pushes an estimated 47 million people into poverty. As climate tipping points approach, these trends exacerbate the divergence between countries that can finance resilience and those excluded from sustainable finance. For the 3.3 billion people already sacrificing social spending to service debt, transformation cannot remain aspirational.

The reform agenda follows directly from the paradoxes. Integrate sustainability into credit assessment frameworks and reduce mechanistic reliance on ratings. Expand regional and multilateral safety nets to absorb climate and macro shocks. Mobilize larger concessional pools under the post-2025 NCQG and related initiatives. Ensure a fairer sharing of transition costs between North and South. Political institutions must rise to match mathematical necessities. Breaking the trap requires aligning debt, sustainability, and development finance so countries are not forced to choose between solvency today and resilience tomorrow.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Alan Gelb, Dhruba Purkayastha, Anit Mukherjee, and Jeffrey D. Bean for their review of an earlier draft of this paper. This background paper reflects the personal research, analysis, and views of the authors and does not represent the position of the institution, its affiliates, or partners.

Cover image courtesy iStockPhoto: CHUYN

Note: Citations and references can be found in the PDF version of this paper available here.

* Udaibir Das is a Visiting Professor at the National Council of Applied Economic Research, a Senior Non-Resident Adviser at the Bank of England, a Senior Adviser of the International Forum for Sovereign Wealth Funds, and a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation America.