By: Udaibir Das

This article originally appeared in OMFIF on October 16, 2025.

The sovereignty premium has become the quiet tax of our time

At the 2025 International Monetary Fund-World Bank annual meetings, discussions on financing development goals highlight an increasingly pressing reality: the growing economic cost countries incur to achieve financial autonomy. This sovereignty premium is becoming visible across sovereign balance sheets.

Global public debt is expected to surpass 100% of gross domestic product by 2029, the highest level since 1948 – but this masks the real cost: collateralised revenues, yield sacrifices and balance sheet erosion, not just higher spreads. Understanding how the premium is extracted, who bears the cost and what this means for the international financial system matters. The premium buys time, not escape.

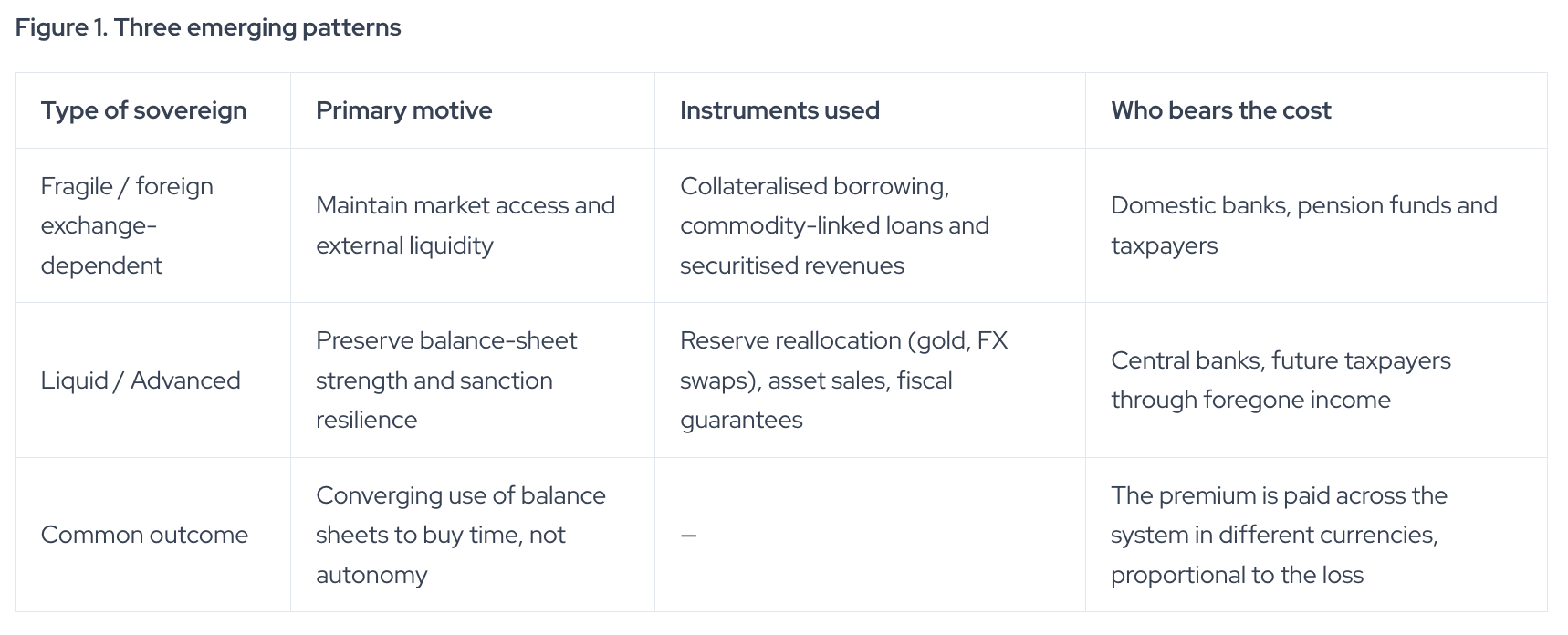

The new reality is that sovereigns are using every part of their balance sheet to secure liquidity. The difference now lies not in whether they pay, but in how they pay and in what form. The mechanics of this premium differ between fragile and advanced economies, but the logic is converging in striking ways.

External borrowing and revenue securitisation

The first channel is via external borrowing under tightening collateral constraints. Countries are increasingly issuing new debt not to finance investment but to manage redemption pressure. In February 2024, Kenya raised $1.5bn at 9.75% to repurchase part of a $2bn Eurobond. Investors demanded stronger covenants and margin triggers, effectively turning sovereign borrowing into quasi-secured lending. Autonomy itself became the collateral. Comparable practices – collateralised oil pre-payments, escrowed export receipts and margin-call clauses – are now common across several African and frontier economies.

The second channel is revenue securitisation and asset monetisation. Governments are borrowing against future income or selling public assets – such as ports, utilities or commodity flows – to raise near-term cash. These transactions provide liquidity today but mortgage fiscal capacity tomorrow. Once pledged, those flows are lost to future budgets. Liquidity comes at the price of ownership.

The third is through reserve composition and the yield sacrifice. The geopolitics of sanctions have altered how reserves are held. Central banks are substituting interest-bearing securities for gold and other non-yielding assets to insulate against seizure risk. Poland announced plans to raise its gold allocation from 20% to 30% of reserves. The World Gold Council’s 2025 survey reveals that 95% of central banks anticipate further accumulation, the highest ever recorded. Such ‘insurance’ reduces reserve income, constrains monetary policy and strengthens fiscal dominance. It is a silent cost embedded in prudence.

Domestic financial repression and restructuring

Domestic financial repression and restructuring is the fourth channel. When external options close, governments turn inward – lengthening maturities, freezing coupons or forcing domestic investors to absorb losses. Ghana’s 2023 Domestic Debt Exchange, Egypt’s accelerated state-asset sales and Argentina’s repeated conversions of central bank paper all show how the burden migrates home. The IMF’s latest Global Financial Stability report confirms that overreliance on narrow domestic investor bases – particularly when driven by financial repression – compounds rather than resolving the premium.

Each of these channels deepens rather than relieves fragility. Higher rollover costs accelerate debt accumulation, lower-yield reserves weaken central bank transmission and domestic expropriation erodes confidence. A country rolling over $20bn annually and paying 100 basis points more forfeits $200m every year – resources that could be diverted to infrastructure or climate adaptation. The IMF’s analysis confirms that decades of accommodative conditions have ended: interest rates have risen sharply while debt has continued to accumulate, fundamentally altering fiscal sustainability dynamics. The arithmetic of seeking financial autonomy has become subtractive.

How technology plays a role

Technology is compounding the premium, as finance grows more segmented, digital and sanction-sensitive. Over 130 jurisdictions are exploring or piloting central bank digital currencies. They promise efficiency yet introduce surveillance, convertibility and cyber-resilience risks. The premium now includes technology risk, layered on top of credit and policy risk. Sovereignty has become a securitised, technology-embedded good.

The distribution of the cost is politically uneven. Those who design or negotiate the transactions seldom bear their consequences. Pensioners, taxpayers and future generations do. When regimes change contractual rules – through restructuring or coercive exchanges – investor expectations shift, and term premia rise. The pursuit of control compounds the loss of it.

Globally, these premiums reveal a deeper systemic fracture. As advanced economies weaponise sanctions and payment networks, developing countries diversify reserves into defensive assets. But diversification without yield erodes income and credibility. The system is fragmenting into defensive balance sheets rather than co-operative ones. Everyone is hoarding safety; few are creating liquidity. The result is insurance without assurance.

Three directions could temper the premium

First, regional reserve pooling can reduce the need to hoard costly, idle assets. Shared high-quality collateral would mutualise sanction risk and preserve yield. Yet political obstacles are formidable: countries fear losing control, and coordination among diverse economies remains elusive. The Chiang Mai Initiative’s limited activation during crises illustrates these constraints.

Second, with proper preconditions in place, deeper local-currency bond markets can replace serial foreign borrowing. Credible yield curves, disciplined primary dealers and transparent buybacks would help rebuild trust. However, this requires credible institutional development, macroeconomic stability and investor confidence that many countries lack. Thin markets will remain vulnerable to sudden stops and capital flight.

Third, cross-border payments systems must be sanction-resilient but anchored in liquid, interest-bearing assets, not static reserves. Building such infrastructure requires a multilateral consensus, precisely when geopolitical fragmentation intensifies. Competing payment architectures – from Project mBridge to bilateral arrangements – may deepen rather than heal fragmentation.

These measures would not eliminate the sovereignty premium, but they could turn it from a penalty into a policy choice. Yet without genuine political commitment and institutional reform, they risk remaining aspirational.

The sovereignty premium has become the quiet tax of our time – a cost imposed not merely by markets but by the design of global finance itself. Each time a state sells an asset to buy time, swaps yield for safety or restructures to preserve liquidity, it pays that tax. What began as a spread on a bond has become a spread across the sovereign balance sheet. The 2025 annual meetings have made clear that incremental adjustments will not suffice. Until new institutions and norms emerge, sovereigns will continue to pay in basis points and in ownership and discover that what the premium buys is not sovereignty, but postponement.

Udaibir Das is a Visiting Professor at the National Council of Applied Economic Research, a Senior Non-Resident Adviser at the Bank of England, a Senior Adviser of the International Forum for Sovereign Wealth Funds, and a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation America.