By: Udaibir Das

This article originally appeared in OMFIF on November 28, 2025.

2026 will determine whether philosophical ambition becomes institutional reality.

At the G20’s 20th meeting in Johannesburg in November 2025, the Declaration placed the African humanist Ubuntu philosophy – ‘I am because we are’ – at the centre of its framing for global economic governance.

This was more than rhetorical flourish. The statement reflects a convergence of analysis across multilateral institutions, how Africa’s economic trajectory has become central to global financial stability and the prevailing architecture is no longer adequate to manage the resulting interdependence. The coming year will determine whether this conceptual shift translates into institutional reform.

Structural pressures and the new consensus

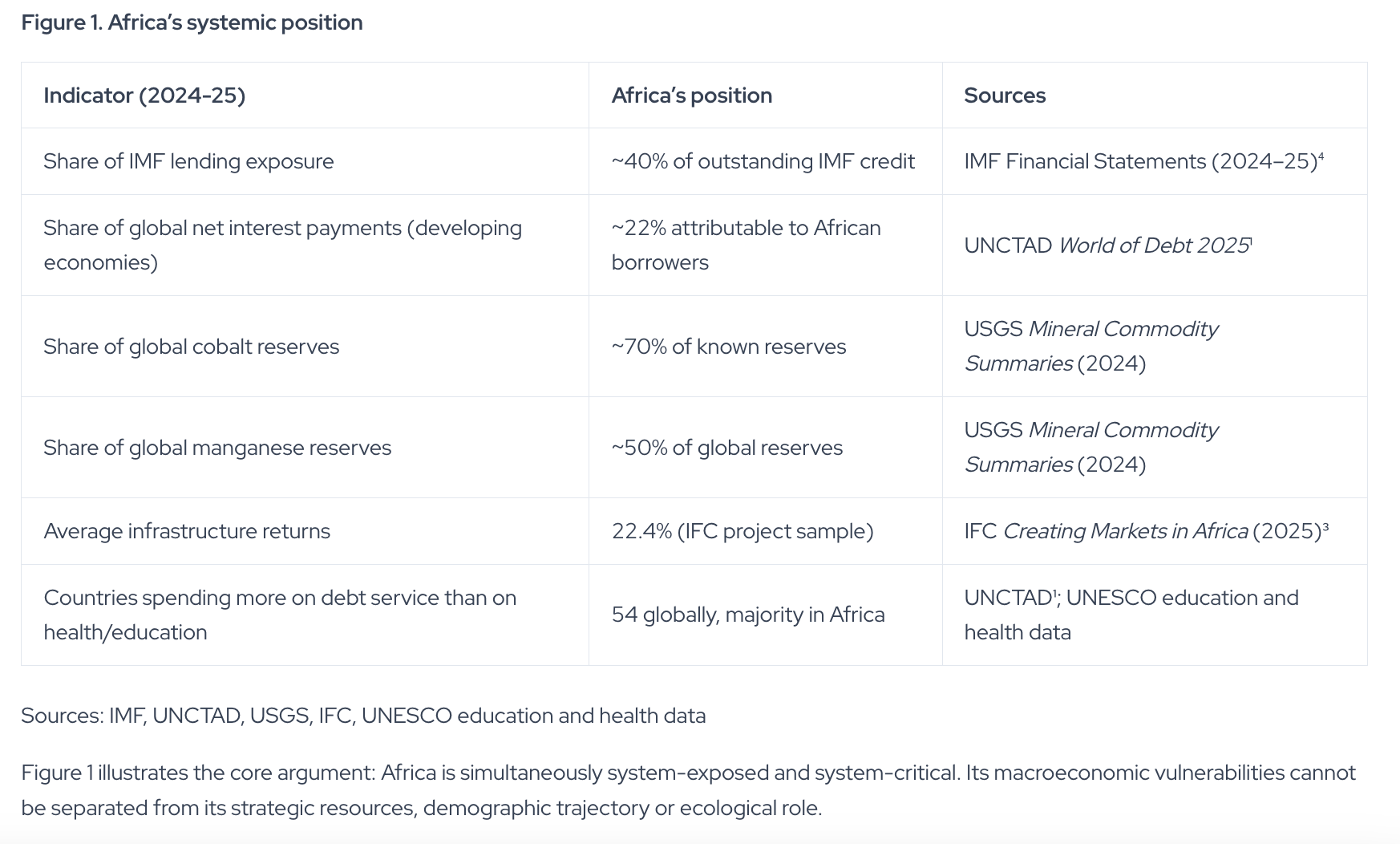

Across 2025, a surprisingly coherent diagnosis emerged from the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and COP30. Developing countries paid an estimated $921bn in net interest in 2024, while approximately 3.4bn people now live in economies spending more on debt service than on health and education combined. These figures do not merely indicate cyclical stress; they describe a structural imbalance that is undermining fiscal resilience and suppressing long-term investment.

Rather than reverting to conventional discussions of temporary liquidity support, the emerging consensus centres on three mutually reinforcing shifts: the broader adoption of state-contingent sovereign instruments; the systematic correction of risk mispricing in African capital markets; and greater collective bargaining power among African borrowers. Together, these shifts represent an attempt to align the financial architecture with the macroeconomic realities African countries face.

State-contingent finance

For many African economies, volatility – not stability – is the baseline. Climate-related losses of 2-3% of gross domestic product per year, combined with commodity-price swings that add around 1.5% to fiscal volatility, create a macroeconomic environment poorly served by traditional debt contracts. The prevailing system compounds this instability by forcing sovereigns to borrow at elevated spreads, often above 700-900 basis points, when their repayment capacity is at its weakest.

State-contingent instruments provide a design-based response. By suspending payments when independently observable triggers, such as rainfall deficits, commodity price collapses or GDP contractions, are breached, they transform sovereign borrowing from a procyclical amplifier into a countercyclical stabiliser. Model-based simulations indicate potential reductions in fiscal uncertainty of roughly 18-22%. Trevor Manuel’s Africa Expert Panel has outlined operational templates that rely on verifiable data sources and minimise the risk of discretionary activation. Nigeria’s experience illustrates the stakes: avoiding three emergency borrowing episodes per decade could save approximately $4.2bn – resources equivalent to the cost of immunising all children in West Africa.

Correcting systematic risk mispricing

A second pillar of reform addresses a long-standing anomaly: African infrastructure investments generate high returns, 22.4% on average in International Finance Corporation samples. Yet, African sovereigns continue to face borrowing costs 400-500bp above peers with comparable repayment histories. Part of this discrepancy reflects structural features. Still, a major share stems from the concentration of sovereign credit assessments among three major rating agencies whose methodologies often overstate macro-financial risk in African contexts.

The sovereign-ceiling convention, which prevents private borrowers from being rated above their sovereign even when fundamentals warrant stronger ratings, remains particularly distortive. Kenya’s mobile-money ecosystem, with default rates around 0.3%, continues to face misaligned borrowing costs. The African Credit Rating Agency, established in 2025, has begun systematically documenting these inconsistencies.

Under upper-bound estimates, correcting the most distortionary methodological assumptions could unlock between $2-3tn in productive investment over a decade, figures consistent with the continent’s infrastructure financing gap and the cumulative impact of lower sovereign spreads and improved project bankability.

This recalibration gains further significance as energy-transition dynamics evolve. Africa possesses roughly 70% of global cobalt reserves and around half of global manganese deposits – minerals essential to electric vehicle batteries and steel production. COP30’s valuation of carbon sequestration in the Congo Basin at approximately $150bn annually underscores the extent to which African ecological assets underpin global climate stability. Yet current risk models seldom incorporate these structural contributions.

Coordinated bargaining

Fragmented negotiation has historically reduced African borrowers’ leverage, leaving them exposed to higher spreads and less favourable contractual terms. Concentrated creditors, whether private bondholders or official lenders, benefit structurally from unified positions. The Borrowers’ Club, to be formally launched in Addis Ababa in early 2026, aims to correct this asymmetry. By standardising key clauses, sharing contract templates and synchronising restructuring timetables, participating countries seek to narrow information asymmetries. Early modelling suggests that such coordination could reduce refinancing costs by 125-175bp, equivalent to around $11bn annually on current external debt stocks.

The initiative coincides with a reassessment inside the IMF. Africa’s present 5.2% voting share sits awkwardly alongside the fact that African countries account for roughly 40% of the IMF’s outstanding lending. Movement towards an 8% voting share, while still modest relative to broader reforms required, would represent a meaningful shift in global economic governance.

Remaining gaps

Despite stronger analytical convergence, three weaknesses persist. Technology remains insufficiently integrated: blockchain-based registries, artificial intelligence-driven risk analytics and automated smart-contract triggers could materially reduce transaction costs but remain underdeveloped in global standards. Private-creditor incentives remain poorly aligned with systemic requirements, particularly given that private lenders hold roughly 61% of Africa’s external debt. The risk of holdout behaviour, seen in several recent sovereign cases, remains significant. Oversight mechanisms also lag behind ambition. Historical G20 compliance averages around 15%; without transparent monitoring, political commitments may not translate into implementation.

Inflection point

The year ahead constitutes a decisive test. The launch of the Borrowers’ Club in Addis Ababa, the design of a new refinancing mechanism in April 2026 and the IMF quota review later in the year form a sequential assessment of political resolve and institutional capability. Whether the philosophical framing articulated in Johannesburg becomes embedded in practice will depend on decisions taken over the next 12 months.

Ubuntu economics does not invoke moral claims. It advances a structural argument: Africa’s demographic momentum, mineral endowments and ecological assets are central to global prosperity, and instability in the region imposes system-wide costs. The reform frameworks are now primarily in place. The question is whether the political and institutional conditions of 2026 permit their implementation.

If this alignment holds, Africa’s reform agenda could mark the most significant recalibration of global finance since the early 2000s. If it falters, the system will remain constrained by an architecture increasingly misaligned with the realities of an interdependent world.

Udaibir Das is a Visiting Professor at the National Council of Applied Economic Research, a Senior Non-Resident Adviser at the Bank of England, a Senior Adviser of the International Forum for Sovereign Wealth Funds, and a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation America.