By: Udaibir Das

This article originally appeared in OMFIF on December 3, 2025.

The continent’s bid to rebalance global finance

Could there be a moratorium on further studies diagnosing what ails African development? The continent has been examined, measured and prescribed to exhaustion – yet the patient deteriorates.

Since 2000, multilateral institutions have catalogued the same barriers: mispriced capital, unsustainable debt, illicit outflows, and governance asymmetries. What Africa lacks is not diagnosis but structural change. The Trevor Manuel G20 Africa Expert Panel Report, released during South Africa’s historic G20 presidency, deserves to become the last word – not because it discovers new pathologies, but because it finally prescribes systemic treatment.

The report reframes Africa’s constraints as a single system of mispricing, debt compression and governance asymmetry. Its proposals for refinancing, collective bargaining and International Monetary Fund quota reform mark the first coordinated attempt to shift power within the international financial architecture.

The Manuel framework

In my view, this report sketches what could become Africa’s first genuine Bretton Woods moment. To be precise, Bretton Woods in 1944 did not merely create institutions, it embedded a new power balance into global architecture. The US and the UK wrote rules reflecting their interests and those rules shaped capital flows for decades.

The Manuel framework proposes something analogous: not adjustment within existing laws, but contestation over who writes them. Whether it succeeds is uncertain, but ambition is structural, not incremental.

The arithmetic of transformation

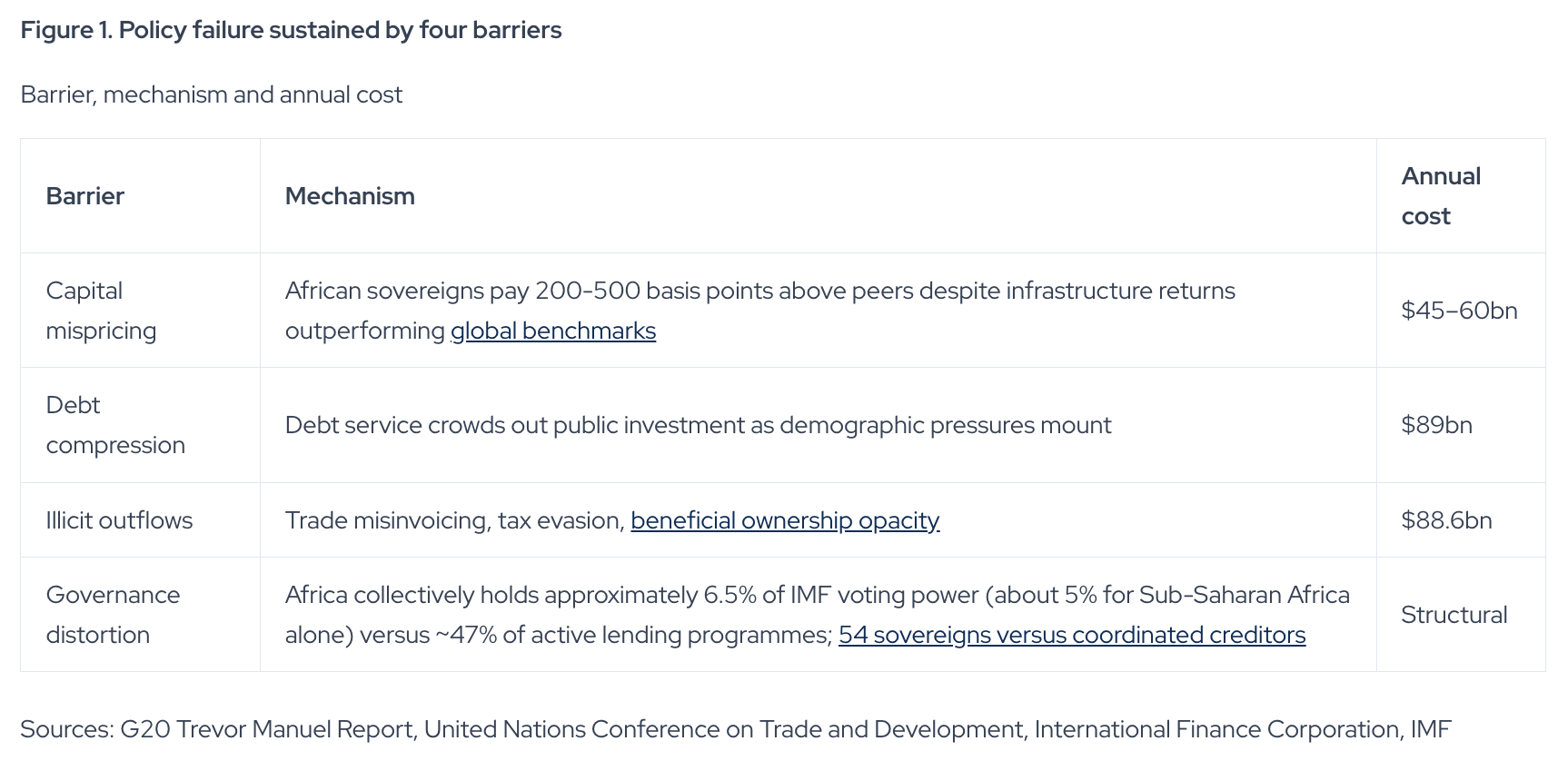

By 2035, Africa must integrate a $3.4tn intra-continental market under the African Continental Free Trade Area, according to African Union and McKinsey estimates, electrify 600m off-grid citizens and absorb 500m young workers into productive employment. Infrastructure financing requires approximately $130-170bn annually; current flows reach barely half of that. This financing gap is the result not of market malfunction but policy shortcomings reinforced by four interlocking barriers.

Taken together, these outcomes constitute a systemic equilibrium rather than a collection of discrete imbalances.

Each barrier reinforces the others. Mispriced capital raises borrowing costs; higher costs expand debt burdens; expanding burdens compress fiscal space; compressed space weakens institutions; weakened institutions worsen risk perception, which then further misprices capital.

Elevated premia mechanically increase debt service costs; higher debt service compresses fiscal space and limits public investment; constrained investment slows productivity growth and institutional development; weaker institutional performance feeds back into heightened perceptions of risk; and those perceptions then justify the continuation of elevated premia.

Illicit outflows drain resources that could be used to service debt sustainably. Governance asymmetries ensure restructuring favours coordinated creditors over fragmented debtors.

Previous interventions failed because they isolated variables. The Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative reduced stocks but left flows untouched. The common framework offered rescheduling without stock reduction. Rating reforms promised transparency without accountability. Each treated one symptom while others festered. I have watched this pattern repeat across three decades of debt initiatives.

Breaking the equilibrium

The Manuel framework attacks all four barriers simultaneously – the only pathway capable of shifting the system to a new equilibrium.

A strategy that tackles these barriers individually cannot change outcomes; the system reverts to its previous equilibrium unless multiple levers move together. The proposed Jubilee Fund would be capitalised through options, including limited IMF gold revaluation gains or new special drawing rights allocations, enabling debt stock reduction rather than mere deferrals.

The logic is plain: rescheduling preserves net present value for creditors while extending distress for debtors; only principal reduction restores fiscal space. The Brady Plan proved this in Latin America, where 30-35% haircuts catalysed a decade of expansion.

The Borrowers’ Club is, in my assessment, the most consequential innovation. Embedded within the AU, it would harmonise positions on workouts, rating methodologies and climate-finance access. Rather than 54 states negotiating individually against coordinated creditors – including private holders of approximately 43% of African external debt – the Club would create countervailing coordination.

The AU’s Lomé Declaration of May 2025 laid the groundwork: only four African countries have applied to the common framework and completed resolutions have taken over three years. Coordinated positions carry more credibility than isolated ones and shared analytics narrow information asymmetries.

This structural logic extends to governance, where the distribution of decision-making power determines the boundary conditions for all other reforms. On governance, the report advocates an externally anchored IMF review shaped by strengthened African representation.

Africa holds approximately 6.5% of total IMF voting power (around 5% for sub-Saharan Africa alone) while receiving close to half of the Fund’s loan commitments. The 2024 addition of a 25th executive board chair was a modest step but inadequate to the scale of imbalance. Movement towards meaningful quota reform would signal that architecture can evolve.

The path ahead

Reform windows in multilateral systems open rarely and close quickly. The 2026 calendar is unusually aligned: the Borrowers’ Club convenes in Addis Ababa in February; the African Development Bank issues its first climate-resilient bond in Q2; IMF Board papers on refinancing land in April; the 17th quota review concludes in October.

If these milestones hold, participating economies could redirect 3-4% of gross domestic product from debt service to human capital, infrastructure and climate resilience. This is not a marginal gain.

But none of it is automatic. Creditors must accept losses; institutions must cede authority. With G20 implementation rates averaging around 15%, the burden of collective discipline falls on African governments. History shows how quickly such initiatives fracture when creditors offer bilateral inducements to individual states. Domestic political transitions, exposure to local-currency debt and variation in creditor composition will further complicate attempts at sustained coordination.

The question that remains is whether these proposals can survive the political and incentive pressures that accompany real-world implementation. The Manuel report has clarified the stakes and sketched the path.

Whether Africa consolidates behind this agenda – and whether institutions yield – will determine whether 2026 marks a genuine inflection or another cycle of analysis without consequence.

Udaibir Das is a Visiting Professor at the National Council of Applied Economic Research, a Senior Non-Resident Adviser at the Bank of England, a Senior Adviser of the International Forum for Sovereign Wealth Funds, and a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation America.