By: Brian Webster, Alan Gelb, and Anit Mukherjee

The following piece originally appeared as a blog post for the Center for Global Development on December 19, 2025.

Digitizing payments, particularly government-to-person (G2P) payments, has been a key focus of the digital development community. Shifting the payment of social transfers from cash to direct deposit via bank or mobile money accounts can directly improve efficiency for governments and convenience for beneficiaries. It may also produce positive spillovers such as boosting financial inclusion and empowering women. But do these spillovers materialize, and under what circumstances?

We explored these questions as part of a 2023 study of Bangladesh’s Primary Education Stiped Program (PESP). Here, we revisit that study with a specific focus on what the Chittagong Hill Tracts can reveal and how that might inform the future of the program.

What we heard from mothers in 2023

PESP—a government program that pays stipends to mothers of primary-school children— transitioned from cash to digital payments in 2017. Two years later it switched to a new payment service provider, Nagad. To assess whether recipients were really benefiting from digital G2P, we surveyed 1,092 mothers across Bangladesh.

The results were encouraging. Mothers overwhelmingly preferred payment through mobile wallets over cash handed out at their children’s schools (93 percent), and they preferred Nagad to the previous payment provider (90 percent). There was evidence that the transfers themselves were having non-material benefits as well, with 73 percent of mothers reporting that PESP had increased their involvement in household decision-making.

However, whether mothers used their mobile wallets for transactions beyond cashing out PESP stipends was a more complex story. For women who indicated that they had never owned a mobile wallet before, using their PESP account for things like transferring funds was associated with a mix of personal attributes, especially being able to read a text message and seeing a reason beyond PESP for opening an account. Only about 10 percent of mothers new to mobile financial services who could not read or who could not recall a motivation for having a wallet prior to PESP did anything more than cash out their benefits.

Other measures of empowerment were mixed as well, with a third of mothers claiming that they themselves controlled the stipend, as opposed to a male or jointly. Furthermore, while we explored the urban-rural divide in our survey, our results said little about regional and household factors that our previous research has shown can influence outcomes such as the use of digital payments.

What can we learn from the experience of the Chittagong Hill Tracts?

To look more closely at such contextual factors in shaping PESP account usage and indicators of empowerment more broadly, particularly among women who had not previously owned a financial account (mobile or otherwise), we examined the results from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). The CHT region is unique in Bangladesh. Poor, predominantly rural, and relatively sparsely populated, it is tucked away along Bangladesh’s southeast border and is defined by steep slopes that contrast to the rest of the low-lying country. It is also culturally diverse, with roughly half the population comprised of 11 indigenous groups with distinct languages and traditions.

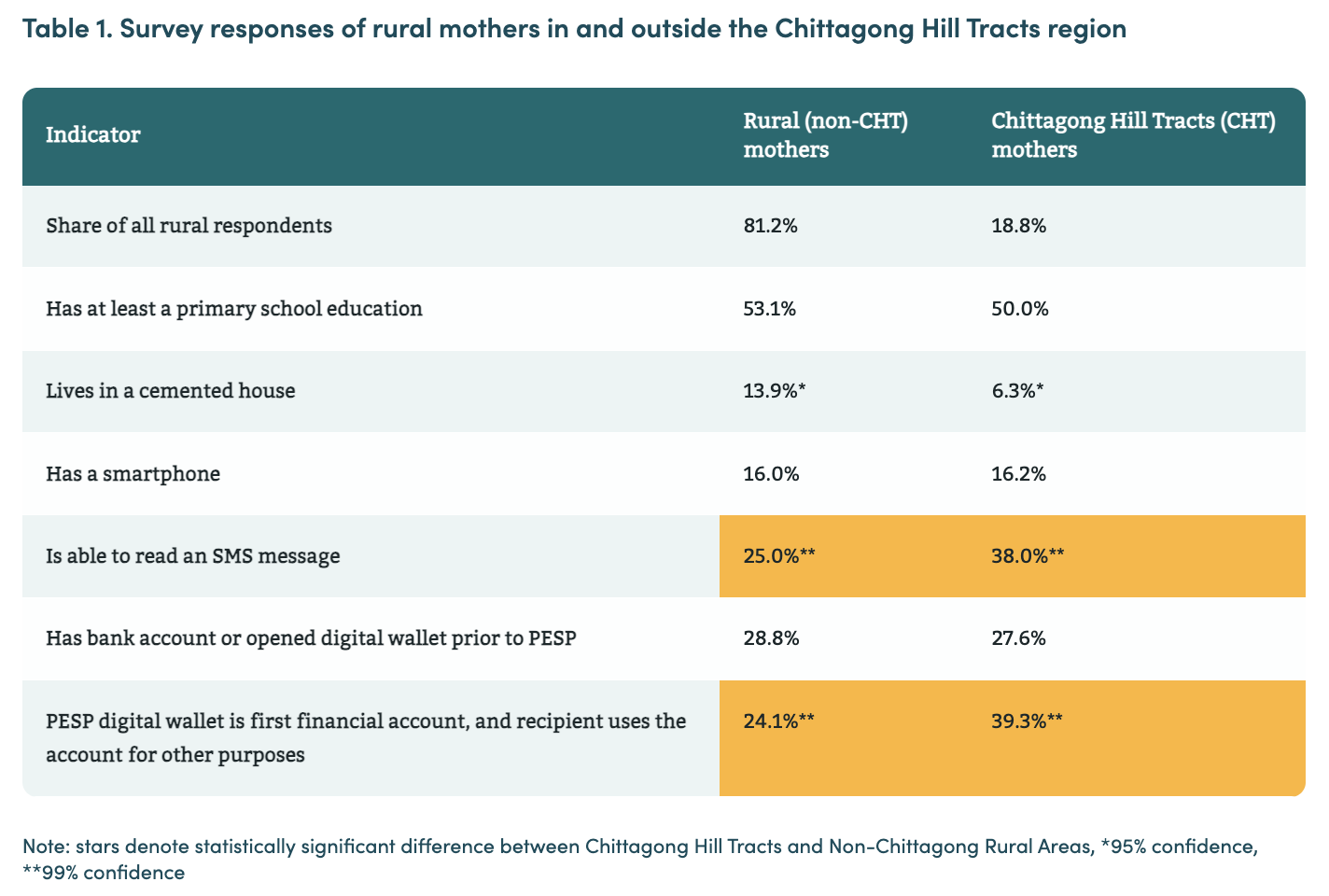

In many respects, survey responses from the Chittagong Hill Tracts were comparable to those from other rural areas of Bangladesh, with similar levels of education and baseline financial inclusion. But mothers from the CHT region were more likely to report being able to read a text message, and in turn more likely to use their PESP wallet for things beyond cashing out if they had never had an account before (see Table 1).

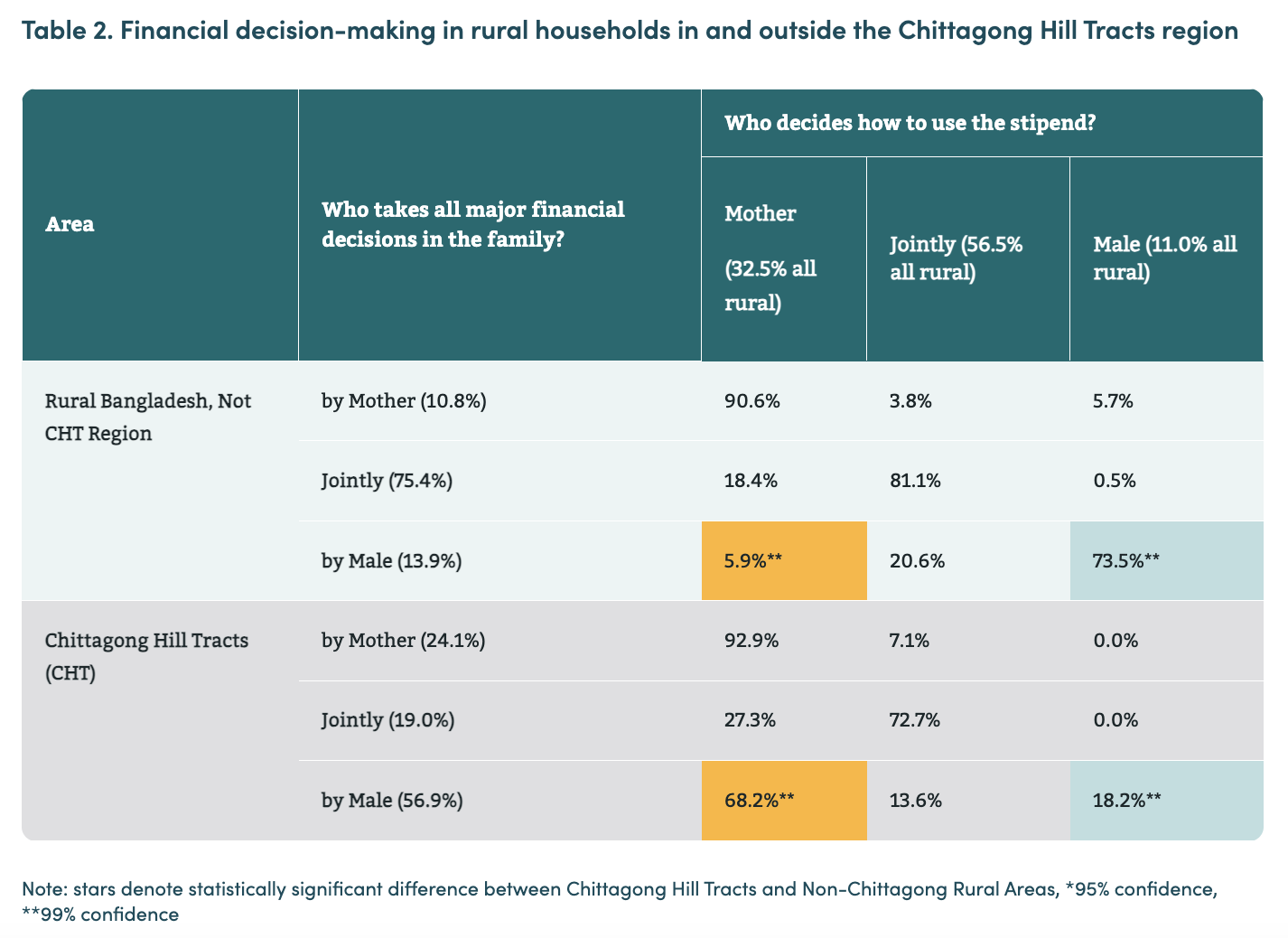

Not only that, but mothers from the Chittagong Hill Tracts were far more likely than other rural respondents to report that they themselves controlled the stipend. Two-thirds of mothers from the CHT region reported that they made decisions about how the stipend was spent, versus just under a quarter of other rural recipients.

This was especially true for mothers in households with male-dominated finances. The vast majority of PESP recipients we sampled said that major financial decisions were managed jointly, and so was the stipend. In households in which men were reported to make the big decisions on their own, very few mothers claimed to have say over how the stipend was spent. But while mothers from the CHT region were more likely to indicate that a man controlled the household finances, such women were more than ten times as likely to say they themselves controlled the stipend (see Table 2).

It’s difficult to draw firm conclusions from these results. The survey included only 142 respondents from the CHT region and was not designed to compare that region to the rest of rural Bangladesh.

That said, these findings might hint at the role of autonomy in the empowerment of women through financial inclusion. Previous studies have found that only about a quarter of rural women in Bangladesh participate in the labor force but that 41 percent of indigenous women from the CHT region do so. And while the literature is scant, some accounts from the area suggest that indigenous women may have comparatively more freedom of movement in a country that can be constraining. Our results paint a similar picture, with 37 percent of mothers from the CHT region claiming to work outside the home and 56 percent claiming to cash out benefits without being accompanied by a man, compared to 3 percent and 25 percent of other rural respondents, respectively. That’s despite longer average distances to cash-out points in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. Correlation does not equal causation, but it is striking that this region performed remarkably well on our measures of empowerment through digitally distributed PESP transfers.

The results also speak to how difficult it is to encourage account usage among more marginalized groups in society. G2P programs generally, and PESP specifically, have made remarkable contributions to increasing financial inclusion, especially among women. But merely having a financial account and actually using that account are two distinct things, and our results show that for Bangladeshi women who are poorer, less educated, and living in particularly restrictive environments, usage rates are far lower.

Perhaps most concretely, however, the results from the Chittagong Hill Tracts illustrate the importance of literacy in the uptake of digital financial services. Eighty-seven percent of unbanked mothers in the CHT region who could read a text message were using their new PESP account for other purposes, compared to 13 percent who couldn’t read one. Our research has consistently shown that people who are unable to read are less able and less likely to adopt digital financial tools, and this nearly binary result underscores the point. In an isolated and impoverished setting, reading can be a key enabler of, or barrier to, digital adoption.

Implications for PESP

Now might be an opportunity for Bangladesh to incorporate changes to PESP that could help encourage account usage for more disadvantaged recipients. The government’s agreement with Nagad was originally set to run through the (quickly approaching) 2026-27 fiscal year, and despite being effective as a service provider, the company has been mired in controversy of late. While navigating this situation, policymakers would do well to consider what measures could boost account usage among the most vulnerable PESP recipients.

One step would be to increase the number of female financial agents operating in the country, especially in rural areas. Bangladesh has a network of nearly 2 million mobile financial services agents today, but IFC estimates that less than 1 percent of these are women and that rural women in Bangladesh strongly prefer female agents when using mobile financial services. Our own research in Kenya demonstrates that G2P programs can successfully incentivize agents to serve rural communities.

Another possibility is to explore the use of voice-enabled services to encourage account usage among illiterate recipients. While there is still limited information on the effectiveness of voice-enabled payments, India’s Hello UPI and 123pay, which allow users to make financial transactions with phone calls holds promise for allowing those unable to read text messages to use mobile financial services. Service hotlines can help to bolster confidence in digital payment services as well, and AI-driven caller systems could become an efficient way to deliver information to relatively restricted beneficiaries.

Much of what influences positive spillovers from G2P lies beyond the strict purview of digitizing payments, and no approach will instantly transform account usage among marginalized PESP recipients, but such measures could disproportionately assist those mothers in Bangladesh most in need of empowerment through digital finance.