Background Paper No. 37

BY Anit Mukherjee and caroline arkalji

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Digital public infrastructure (DPI) has become a cornerstone of inclusive growth and innovation in the Global South, with Brazil’s Pix and India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) standing out as transformative examples. Together, they account for nearly two-thirds of global instant payment transactions, providing millions of individuals and small enterprises with access to secure, instant, and affordable financial services. These real-time payment systems demonstrate how open, interoperable, and low-cost public digital platforms can expand financial inclusion, strengthen state capacity, and foster public and private sector coordination.

Anchored in the principle of digital payments as a public good, they highlight the importance of promoting innovation with regulatory oversight to drive adoption at scale.

Yet key challenges remain. Existing digital divides and uneven institutional capacity continue to hinder equitable adoption of digital payments, especially across low-income economies. Data protection and interoperability across jurisdictions also require sustained coordination. Addressing these barriers will require strengthening foundational DPIs such as digital IDs and data-sharing frameworks, balancing regulation with innovation to build trust and adaptability, and deepening cross-border cooperation to align technical and regulatory standards. Together, these steps are essential to scaling the PixUPI model and enabling a Global South–led, inclusive digital payments ecosystem.

I. INTRODUCTION

Every minute, millions of people in Brazil and India send money instantly to buy goods, pay bills, or transfer funds to friends and family through digital payment systems that now dominate global real-time transactions. Known as Pix in Brazil and UPI in India, their rapid adoption over the last decade has generated considerable attention. By 2024, UPI and Pix had become the world’s most utilized real-time payment systems, accounting for 48 percent and 15 percent of global transactions, respectively.

The success is not accidental. While they were designed and implemented independently, Pix and UPI are part of Brazil and India’s digital public infrastructure (DPI), built on the principles of inclusivity and interoperability, with a transformative impact on the lives of their citizens. DPI refers to a set of digital building blocks that allow governments to deliver services safely, efficiently, and at scale. Like roads connecting people and markets, DPI connects identities, money, and data. Three systems form its backbone. First, digital IDs, which enable individuals to prove their identities and access a broader range of goods and services. Second, data-sharing frameworks, which allow secure transfers of information across institutions. Third, digital payment systems, which enable governments, businesses, and individuals to send and receive money instantly, at low cost.

Together, this digital ID-payments-data exchange stack incentivizes public and private sector innovation, improves governance, and creates inclusive digital economies.

While many countries have digital payment systems, they operate in silos and are often proprietary in nature (for example, internet banking, mobile payments, and credit cards), which impose higher costs for both providers and users. In contrast, Pix and UPI are based on open protocols and standards that are interoperable across different financial providers regulated by the central bank. Their mobile-native design lowers barriers for those historically excluded from formal financial services but who now have access to mobile phones and cellular networks, while their governance models keep costs low and innovation high.

The significance of these systems extends beyond Brazil and India. As digital payments have become a necessary and critical infrastructure for inclusive digital transformation, Pix and UPI are increasingly viewed as models for the next generation of digital payment systems that other countries can adopt and adapt as per their own needs and priorities. In forums such as the United Nations, G20, and the BRICS, Pix and UPI are recognized as examples of how countries of the Global South can build trusted and low-cost real-time digital payment systems at a population scale. Their rapid and growing diffusion underscores a broader shift: countries are turning to DPI to shape their economic trajectories with digital payments as a key enabler for inclusive growth and better, more equitable development outcomes.

This paper examines how DPI laid the foundation for Pix and UPI, and how these systems can serve as blueprints for future digital payment systems tailored to the needs and priorities of the Global South. First, it describes the evolution of DPI in Brazil and India and analyzes their development, governance, and adoption in each country. It then assesses their broader economic impact, before turning to the lessons from the design and implementation of Pix and UPI as countries adopt a DPI framework to advance financial inclusion and digital payments at scale.

Ii. EVOLUTION OF DIGITAL PUBLIC INFRASTRUCTURE IN INDIA AND BRAZIl

The idea of DPI is not new. The internet and the Global Positioning System (GPS) were both funded by the United States government in the 1970s and 1980s and eventually emerged as global public goods. The COVID-19 pandemic, however, underlined the importance of creating DPI at a population scale with the objective of reaching citizens who needed assistance, including through financial transfers to mitigate the impact of the lockdown measures imposed by countries around the world. This has spurred interest in how countries can create DPI to address developmental challenges, and improve state capacity to do so at the population scale.

At the UN General Assembly session in 2023, DPI was recognized as a critical accelerator to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In 2023, interest in DPI deepened under India’s presidency of the G20, where it became a central theme across multiple workstreams. The New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration recognized DPI as a “safe, secure, trusted, and inclusive,” framework, which is respectful of human rights, personal data, privacy, and intellectual property rights, fostering resilience and enabling service delivery and innovation.

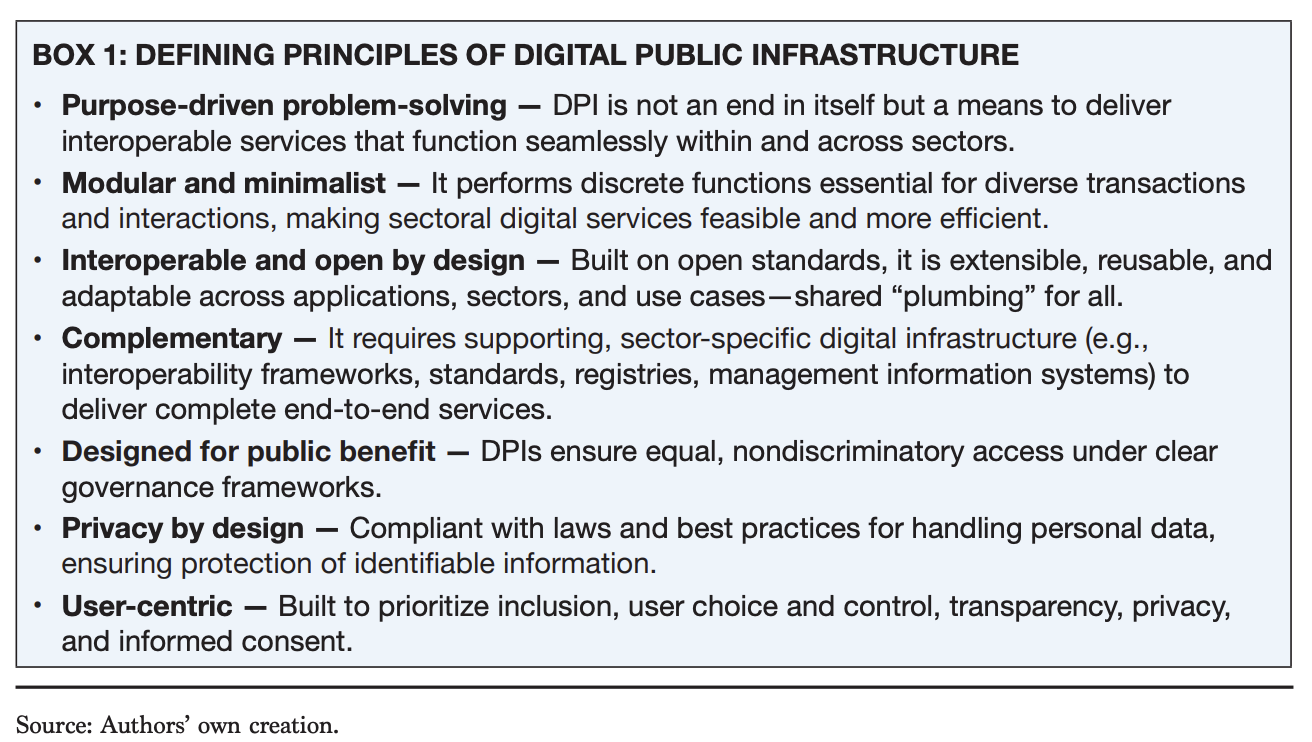

As DPI is a relatively new term, it is presented globally in various forms and with differing levels of usage and outcomes. The term digital public infrastructure can refer to either: (i) a specific operational digital platform that demonstrates these characteristics, and/or (ii) a broader approach to designing and developing digital platforms that incorporate them. Although definitions of DPI are not yet standardized, defining principles are increasingly widely accepted (see Box 1).

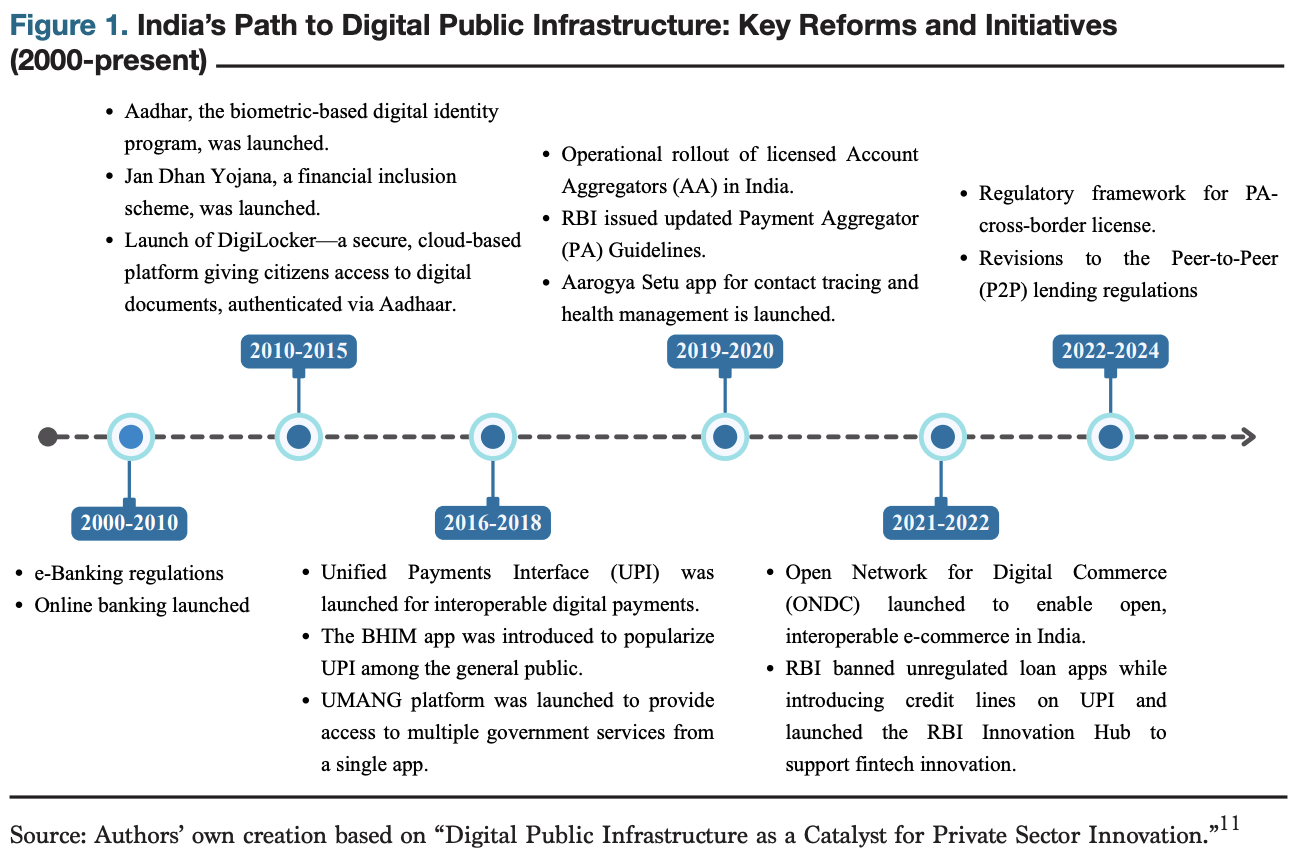

India’s DPI approach has come under the spotlight for transforming the lives of its citizens in just over a decade. Built on open application programming interfaces (APIs), consent-based interoperability, and a three-layered structure of identity, payments, and data, India’s DPI design has enabled the creation of essential government services and platforms, while also allowing private sector players to use these DPIs for innovative business models, all grounded in public trust. It is estimated that by 2030, the economic value added from DPIs to India could reach 2.9-4.2 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

India’s success with DPI demonstrates how modular, interoperable, and inclusive infrastructure can drive large-scale adoption and innovation, offering a potential roadmap for other countries. Aadhaar, UPI, and Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) exemplify these principles (Figure 1). Aadhaar provides a biometric ID for over 1.42 billion citizens. It supports services such as the Aadhaar-enabled Payment System (AePS), Aadhaar Payments Bridge (APB), electronic Know Your Customer (eKYC), and eSign. UPI connects bank accounts to multiple apps, facilitating instant transactions, promoting financial inclusion, and increasingly replacing cash for routine payments. Between 2023 and 2024, it accounted for 70 percent of digital payment transactions, far surpassing credit and debit cards. DEPA provides a secure framework for citizens to access and share their data on their own terms.

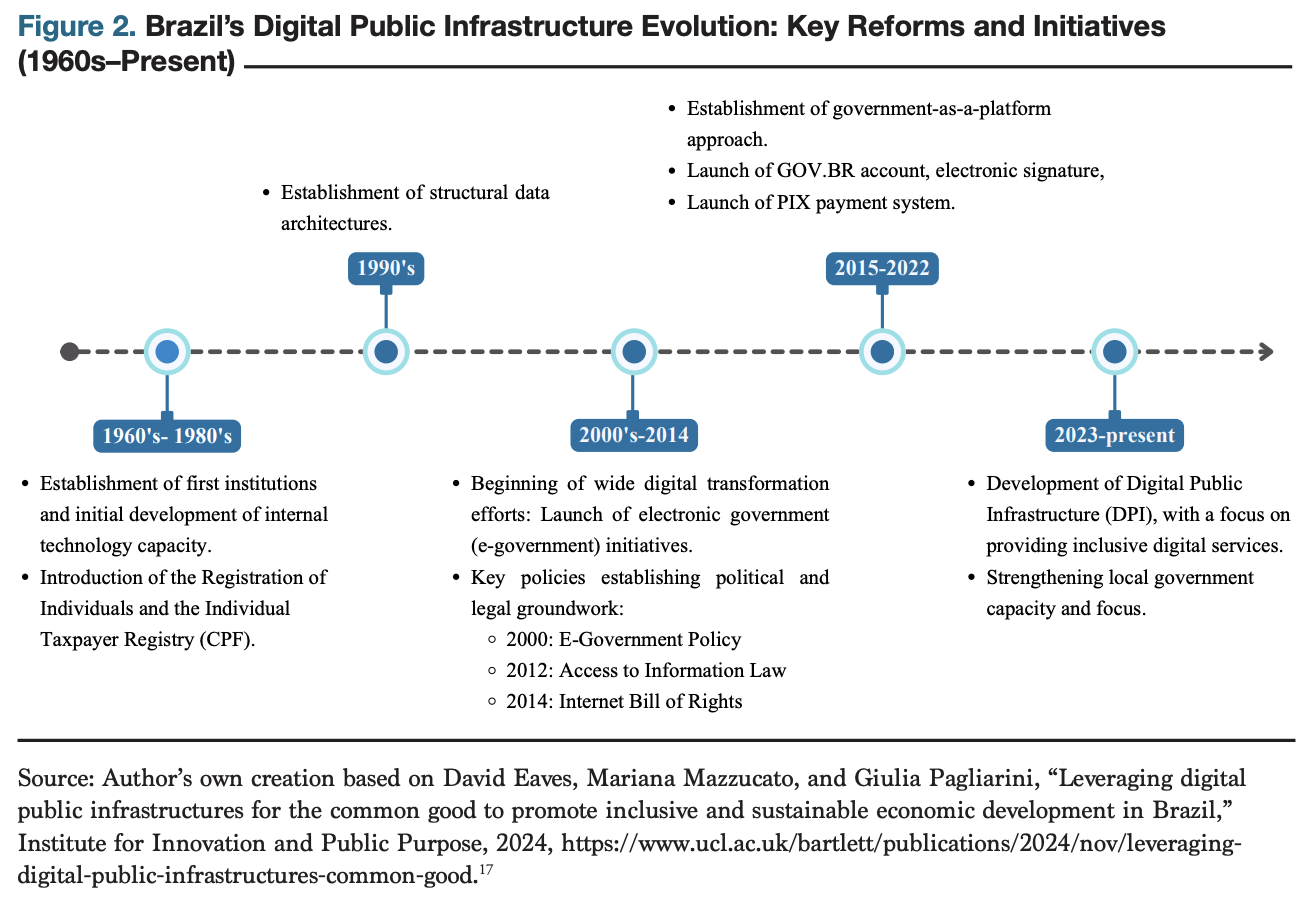

By contrast, Brazil’s DPIs primarily focus on government platforms, with Pix as the main exception. Brazil’s approach to digital platforms has emphasized the modernization of government services, focusing on creating efficient, secure, and user-friendly public systems. While Pix stands out as a widely adopted payment platform reflecting broader DPI principles, most other Brazilian digital initiatives remain oriented toward delivering specific governmental functions rather than building a fully integrated public digital ecosystem.

Brazil’s digital transformation has evolved over six decades (see Figure 2). It began with state-owned information technology (IT) enterprises, which, in the 1960s, built foundational data systems, such as the taxpayer registry, known as CPF. Beginning in 2000, e-government initiatives emphasized transparency, inclusion, and interoperability, supported by key policies such as the Access to Information Act (2012) and the Internet Bill of Rights (2014). In 2019, the shift toward “government as a platform” marked a turning point, with the launch of GOV.BR, electronic signatures, and large-scale service digitalization, which were accelerated further by the pandemic. By 2020, 89 percent of federal services had been digitized, laying the groundwork for a more integrated approach to DPI.

Starting in 2023, the focus has shifted to building foundational DPIs in payments, data exchange, and digital identity. Pix, Brazil’s instant payments system, has become a global benchmark, onboarding over 70 million people by 2022 and projected to contribute $37.9 billion to Brazil’s GDP by 2026 (or 2.0 percent of forecast GDP). Conecta GOV offers secure interoperability through APIs, which have been adopted by approximately 1,000 services, resulting in an estimated savings of $800 million. The new National Identity Card (CIN), linked to the taxpayer number (CPF), anchors Brazil’s digital ID ecosystem and has proven critical in disaster response, such as identifying displaced families during the 2024 floods in Rio Grande do Sul. Alongside these foundational DPIs, domain-specific initiatives in health, education, and the environment, such as the Rural Environmental Registry, are emerging, reflecting the government’s effort to integrate DPI into broader social and sustainability agendas.

III. DPI FRAMEWORK FOR PIX AND UPI

The DPI framework helps explain the success of Pix in Brazil and UPI in India. Both were created not just as payment tools but as public goods, built on openness, interoperability, and scalability to support inclusive, flexible, and locally adapted digital systems.

Inclusive Design and Public Purpose

Inclusive design and public purpose are the foundational principles of DPI, ensuring accessibility for all citizens regardless of socioeconomic background. Pix and UPI embody this by being user-friendly, affordable, and designed to reach those often excluded from formal finance. UPI 123Pay, for instance, enables people without smartphones or internet access to make digital payments via simple phone calls. Pix is free of charge for individuals, operates 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and is increasingly used by municipalities for services like tax and utility payments. Beyond inclusion, their public purpose lies in enabling broad societal impact. They act as backbones for service delivery, unlock innovation and entrepreneurship, and strengthen both local and global digital ecosystems. By prioritizing universal access over profit motives, Pix and UPI demonstrate how DPI can function as an equalizer and provide a replicable blueprint for other countries seeking inclusive digital payments frameworks tailored to local needs.

Efficiency and Public Benefit

Building on inclusive design, Pix and UPI demonstrate how DPI can deliver efficient and tangible public benefits at scale. By significantly reducing the transition and onboarding costs, they make payments instant, secure, and nearly cost-free, saving time and money for millions of users while allowing merchants to pass the savings directly to consumers. Both systems sustain themselves through minimal fees, such as Pix’s 0.22 percent average merchant charge or UPI’s capped interchange, while enabling banks, fintechs, and small businesses to compete on a level playing field. Their architecture improves transparency, generates financial histories that expand access to credit, and provides fertile ground for innovation in services ranging from bill payments and insurance to investment and digital credit. In practice, this demonstrates how efficiency and public benefit, when grounded in transparent governance and open participation, can transform digital payments into public goods that promote affordability, innovation, and long-term financial inclusion.

Open Architecture and Interoperability

Equally important to their success and public benefit is the commitment to open architecture and interoperability, which makes Pix and UPI not just efficient, but adaptable and innovation friendly. Both systems were built as shared public rails on common standards and modular design, allowing banks, fintechs, and third-party providers to integrate seamlessly without creating siloes. UPI's open APIs and extensible protocol have supported the addition of new features, such as offline payments, e-mandates, and purpose-specific vouchers, into the core system. In contrast, Pix's adoption of ISO 20022 standards and its unique identifier (Pix Key) system ensures smooth transfers across institutions and wallets. This openness prevents vendor lock-in, encourages competition, and allows ecosystems to evolve rapidly, with services like QR-code payments, micro-credit, and digital insurance emerging on top of the same public backbone. By mandating interoperability from the start, both platforms turned instant payments into dynamic platforms for continuous innovation.

Security, Privacy, and Trust

The openness and reach of Pix and UPI are reinforced by strong governance and security measures that sustain trust, the cornerstone of any DPI. Transactions require two-factor authentication and device-level verification, such as a phone unlock PIN. Both systems operate on closed financial networks, accessible only to authorized participants, and transactions are end-to-end encrypted and digitally signed to ensure auditability and prevent unauthorized access. While fraud levels remain relatively low, it remains a concern since a large section of the rapidly expanding user base are new to digital payments. To address this, central banks have launched consumer education campaigns and tightened safeguards. Pix enables rapid dispute resolution with immediate account blocking and reversals. UPI offers a real-time, multi-party framework with 24-hour transaction reversals. Regulators have also introduced stricter licensing rules and transfer caps. For example, Brazil's Central Bank recently implemented the "Pix Teto," capping transfers via unauthorized providers at 15,000 Brazilian Real, or roughly $850 and moving up licensing deadlines to enhance security. These safeguards reinforce user confidence and show how public digital infrastructures can maintain security, privacy, and trust.

Adaptability and Scalability

Finally, the adaptability and scalability features of DPI allow it to grow and stay relevant over time. UPI's modular architecture allows new features to be added easily, as seen with UPI Lite, which enables instant low-value payments up to 200 ($2.25) without a PIN on basic phones, expanding access beyond smartphones. Other innovations include programmable bill payments and e-RUPI vouchers. Pix is following a similar path with "Pix Automático" for recurring transfers, offline payments for low-connectivity areas, and small-scale lending tools. Adaptability ensures features can evolve with demand, and scalability ensures reliability as the volume of transactions increases over time. These qualities make Pix and UPI durable, user centric and, future-ready models for other countries seeking to build resilient digital payment ecosystems.

Collectively, these defining principles of DPI illustrate how Pix and UPI realize the promise of DPI, guided by inclusion, efficiency, openness, trust, and adaptability. Their success highlights the potential of digital payment systems, when designed as public goods, to expand access, reduce costs, and promote ongoing innovation. Just as importantly, they demonstrate that robust governance and state capacity are key for sustaining trust and scaling adoption. These lessons extend well beyond Brazil and India, offering a roadmap for countries seeking to build resilient, future-ready payment ecosystems, as we outline in the next section.

IV. PIX AND UPI IN THE CONTEXT OF DPI: INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK, SYSTEM DESIGN, AND ADOPTION

Institutional Framework

India's financial inclusion drive over the last decade enabled the rapid growth of digital payments. Starting in 2014, the Jan Dhan Yojana (JDY) brought almost half a billion people into the banking system within a decade. The proportion of adults with a bank account increased from 34 percent in 2011 to 89 percent in 2024, with women and men equally likely to have access to a formal financial account. Coinciding with the rapid increase in financial access, the government launched UPI in 2016 that now accounts for around 85 percent of all digital transactions in India. The National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), a non-profit entity jointly owned by the Reserve Bank of India and 56 commercial banks, established the principles of the UPI architecture as open, interoperable, and inclusive, providing the institutional framework and regulatory foundation for both the public and private sectors to build payment applications at scale.

Brazil's rapid adoption of digital payments was similarly enabled by a strong institutional framework led by the Central Bank of Brazil (Banco Central do Brasil, BCB). Pix, launched in 2020 as part of the central bank's broader agenda to modernize the national payment system, aimed to enhance competition, reduce transaction costs, and expand access. Designed as a public infrastructure project, Pix required mandatory participation for larger banks and provided incentives for regulated private payment banks to participate, thereby generating immediate network effects. The BCB prioritized user experience throughout the development process, establishing regulations to ensure accessibility, non-discriminatory use, and free peer-to-peer transactions. Fast settlement cycles, network-level transaction limits, and integration of traditional banks, fintechs, and payment service providers created a secure, low-risk environment that fostered innovation, economic growth, and financial inclusion across Brazil.

System Design

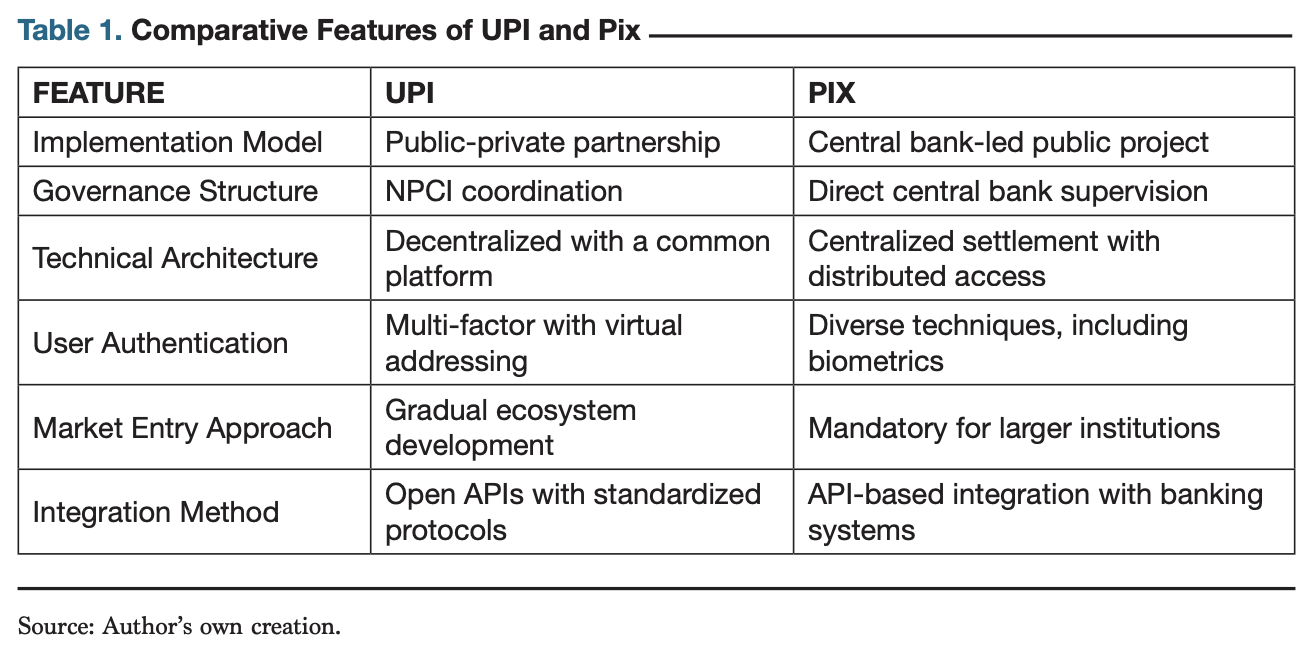

Both UPI and Pix exemplify DPI principles through features such as open APIs and layered interoperability. However, they differ in their governance and technical design. Pix is a central bank-led, state-owned system with centralized settlement and distributed access, while UPI is coordinated by the semi-autonomous NPCI on a decentralized common platform. Brazil adopted the ISO 20022 standard to accelerate the launch of Pix and ensure interoperability, whereas India developed a new XML-based UPI protocol that emphasizes flexibility, pluggable authentication, and real-time dispute resolution. Pix's mandatory participation for large institutions accelerated network effects, while UPI's open API framework fostered fintech innovation, both within banks and among fintechs. Table 1 summarizes these comparative features.

Adoption at Scale

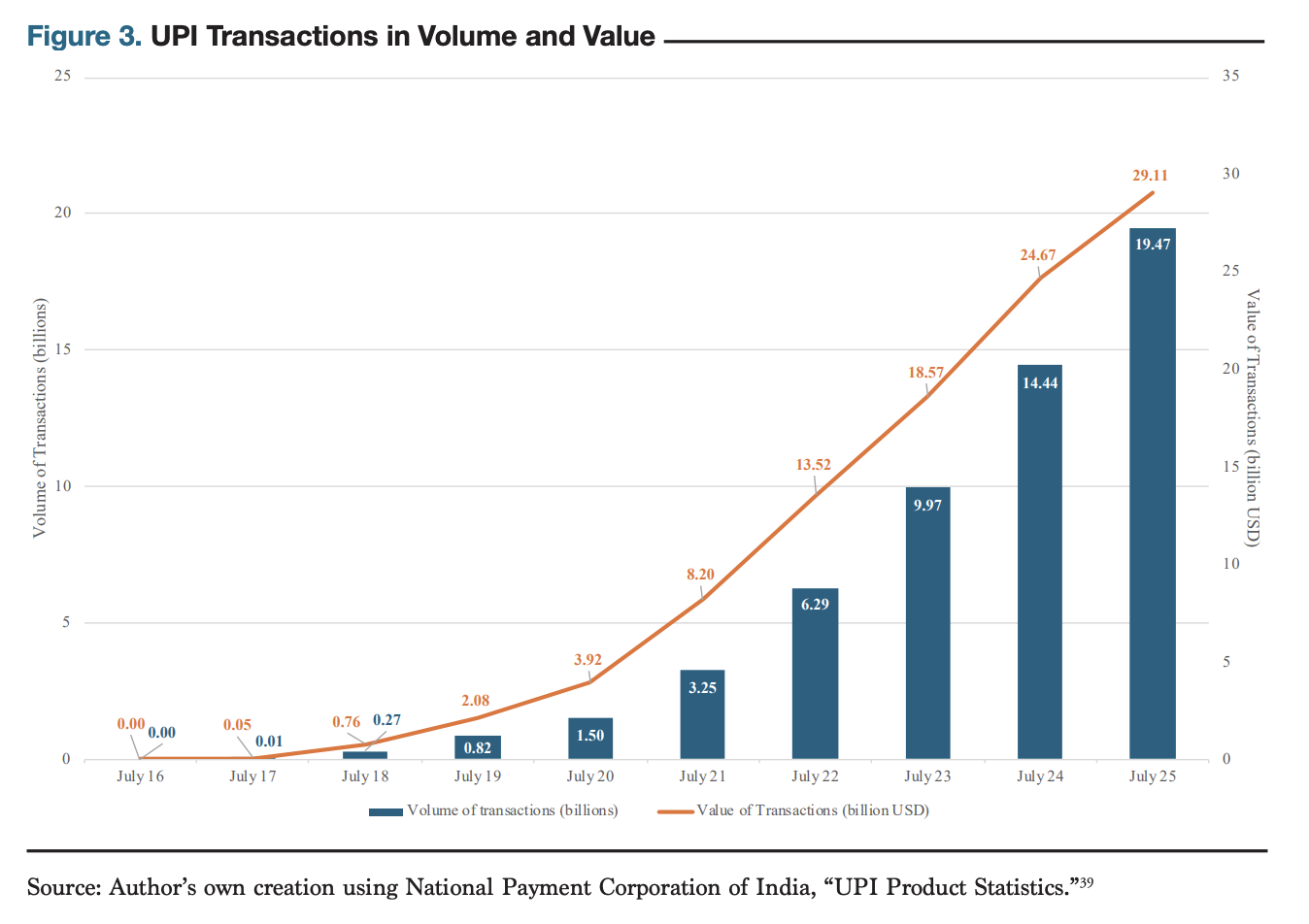

The uptake of UPI and Pix has been remarkably rapid. In July 2025, UPI processed over $29 billion in payments through 19.46 billion transactions. In contrast to the same month last year, when there were 14.43 billion transactions, registering an increase of about 34 percent in just one year. The UPI system now serves over 491 million individuals and 65 million merchants, connecting over 675 banks in a single platform.

The adoption of UPI has followed different pathways across diverse population segments and geographical regions in India. Initially, the adoption was focused in urban areas, with higher concentrations of digitally literate, middle-to-high income users with operating banking connections. Gradually, the system has expanded into suburban and rural areas as smartphone penetration increased by over 75 percent from 2014 to 2024, and telecom infrastructure improved, registering an increase of 285 percent in internet connections during the same period.

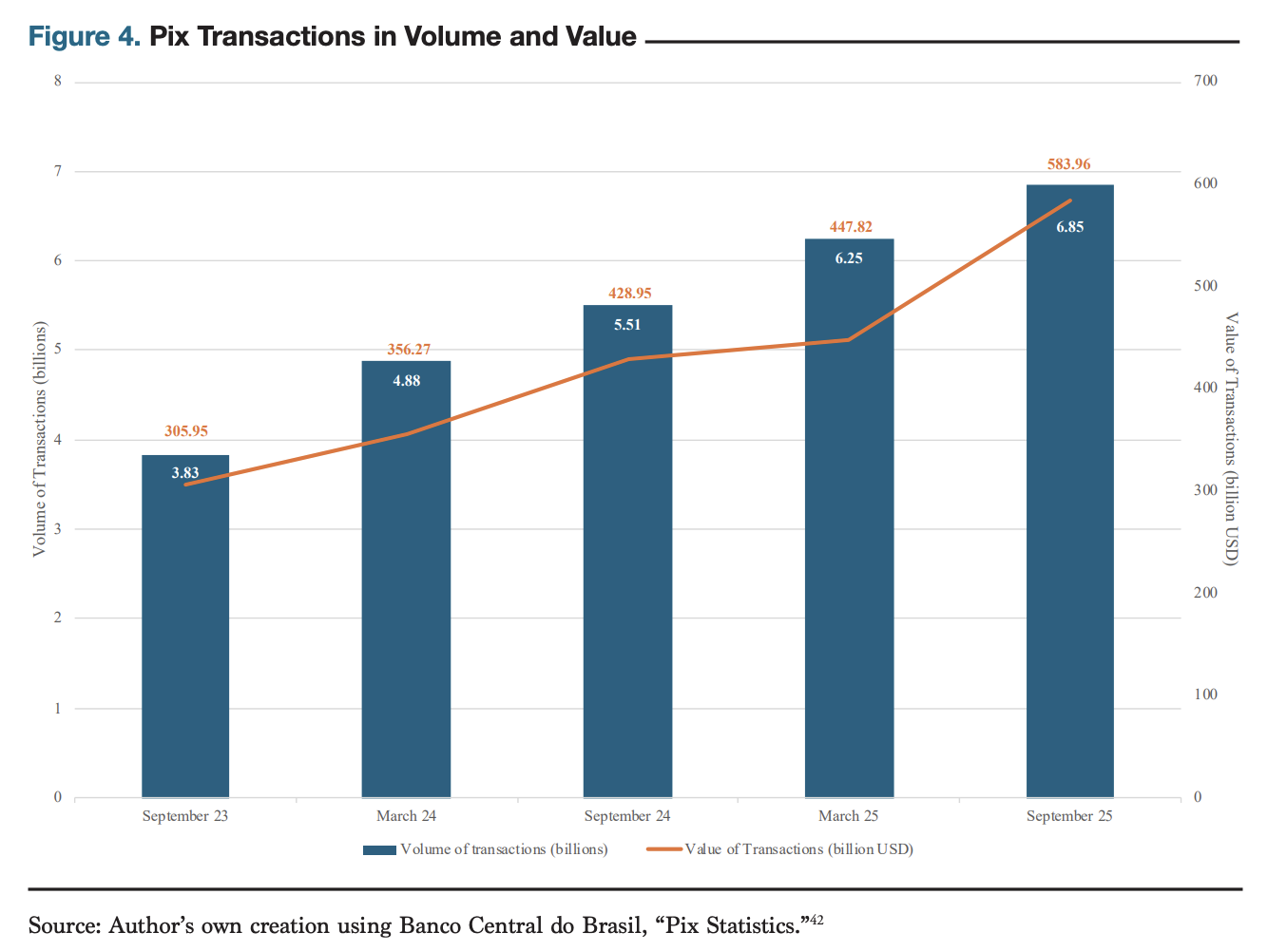

In Brazil, from the launch of Pix operation in November 2020 through July 2025, the number of transactions has increased by about 700 percent across all income groups. Currently, 160 million individuals and over 15 million merchants use the payment system. Pix has had different adoption patterns across Brazilian segments of society, similar to the Indian case. The highest adoption rate initially was among young, urban populations with higher digital literacy and bank accounts. But the system has a progressive penetration in larger demographic segments, such as older age groups and lower-income groups. Demographic analysis also shows outstanding adoption in rural areas and smaller municipalities, where banking infrastructure is limited.

Factors Driving the Widespread Adoption of Pix and UPI

The broad adoption and diffusion of UPI and Pix arise from intentional design choices in technology, governance, and stakeholder engagement. Both systems were designed to make digital payments more accessible and user-friendly, bringing hitherto excluded segments of the population into the digital ecosystem. Unlike traditional retail payment systems, they were built for mobile platforms rather than card-based infrastructure, ensuring payments could be made anywhere without reliance on point-of-sale terminals or ATMs.

Regulatory support and collaboration were crucial in establishing trust and interoperability. In India, NPCI governs UPI with strict rules, while enabling fintechs to offer digital wallets or prepaid payment instruments (PPIs). In Brazil, Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) provides Pix infrastructure and owns its rulebook, which requires mandatory participation from institutions with more than 500,000 accounts and includes precise API specifications that enable seamless integration for payment service providers.

Network effects on both the supply and demand sides have accelerated usage. On the supply side, both UPI and Pix have reliable infrastructure, with NPCI handling transition settlement in India, while BCB processes Pix payments and manages APIs and rulebooks. This enabled seamless interoperability between banks, credit cooperatives, fintechs, and payment institutions. On the demand side, low or zero costs created strong incentives for adoption. In India, UPI transactions are free for users, with minimal or reduced interchanged fees for merchants. In Brazil, Pix payments are also free for payers, while carrying merchant service charges that are significantly lower than those for credit or debit cards, thereby lowering barriers to entry for businesses and promoting widespread usage.

Finally, they have made constant improvements and security enhancements. In India, new features like Bharat BillPay for Business, designed to streamline business-to-business (B2B) transactions, and UPI Circle, which allows users to fully or partially delegate payments to other trusted users to support financial inclusion for those with limited digital capacity. In Brazil, BCB is rolling out innovations such as Offline Pix, for in-person transactions using static or dynamic QR codes at a physical store, rather than online, and "Pix Parcelado," which allows users to pay for purchases in installments, similar to a credit card, along with improved fraud detection and fund freezing protocols. These continuous upgrades keep both systems relevant, secure, and adaptable to the evolving needs of new users.

Impact on Financial Ecosystems and Behavior

Both UPI and Pix have had a considerable impact on financial inclusion, albeit with varying levels of impact across demographics and geographical areas. Pix has been able to reduce transaction costs for person-to-person transfers that incurred substantial fees in Brazil's banking system. Similarly, UPI has been particularly effective in enabling micro-entrepreneurs and small businesses to participate in the digital economy through streamlined merchant payment systems.

Building on the expansion in bank account ownership, UPI has facilitated usage by decreasing the barriers to formal financial services. Populations in areas with limited access to banking infrastructure can now access the digital payments network through mobile phones. By encouraging the adoption of digital payment habits, UPI has reduced the need for physical visits to banks and simplified account management. This has expanded the practical utility of bank accounts that were often opened but remained unused. The payment platform has stimulated micro-entrepreneurship, enabling small vendors and service providers to accept digital payments without the need for point-of-sale systems. As a result, new income opportunities, particularly for women and rural entrepreneurs, have emerged, improving transaction records and reducing the risks associated with cash.

However, despite these gains, large portions of the informal sector continue to face challenges in accessing digital financial services due to factors such as poor internet connectivity, low digital literacy, and limited access to smartphones, which continue to hinder full adoption. Additionally, the increased reporting of UPI transactions in the Annual Information Statement has raised concerns regarding Goods and Services Tax (GST) compliance. Many informal vendors fear that sudden increases in digital receipts could trigger tax notices if they are not aligned with previously filed returns, prompting some to remove QR codes or return to cash-only transactions. This tension underscores how regulatory and administrative pressures can impede the adoption of digital payments, despite UPI's role in promoting financial inclusion.

Pix has also had a profound impact on Brazil's financial ecosystem, reshaping both institutional structures and user behavior. Its public-sector design and compulsory integration requirements created an inclusive digital infrastructure that rapidly embedded itself across the banking sector, fintech landscape, and merchant networks. By reducing transaction costs and simplifying access, Pix lowered barriers to digital banking, incentivizing both individuals and businesses to shift away from cash-based practices. For consumers, this has normalized the use of instant digital payments in everyday transactions, deepening engagement with the formal financial system. For merchants and micro-entrepreneurs, the platform's low fees and ease of use have expanded the adoption of electronic payments, generating transaction records that support credit assessments and furthering the formalization of economic activity.

The interoperability of Pix has also spurred fintech innovation, as new entrants leverage the system's infrastructure to develop complementary financial products and services, from digital wallets to small-scale lending platforms. Taken together, these shifts demonstrate how a state-led payments initiative can simultaneously drive efficiency in the financial system, expand access to services, and alter behavioral norms surrounding money management and financial participation. This new approach to building digital payment systems highlights how design choices aligned with the goal of financial inclusion and access can create enabling conditions for rapid adoption, especially when digital payments are embedded within a larger DPI framework. We explore this in detail in the next section.

V. TOWARDS A GLOBAL SOUTH-LED MODEL OF DIGITAL PAYMENTS: LESSONS FROM PIX AND UPI

The success of UPI and Pix as digital-first, mobile-native, inclusive-by-design payment systems has garnered wide attention, especially in countries of the Global South. Their success offers valuable lessons for other countries seeking alternatives to legacy systems that are both costly and ineffective in the context of rapid digital transformation. Our review shows that there is considerable potential for the diffusion of a Pix-UPI model based on the principles of DPI. However, replicating this model requires a careful understanding of policy choices, institutional frameworks, and technology deployment that enabled Brazil and India to create a vibrant digital payments ecosystem at scale within a decade.

Three key lessons emerge from the rapid adoption of Pix and UPI over the last decade. First, universal financial inclusion is a necessary condition for these new digital payment models to be adopted at scale. As noted in Section II, India's financial inclusion accelerated over the last decade, with nearly 500 million adults gaining access to the formal financial ecosystem through bank accounts, a large majority of which were opened through the Aadhaar e-KYC process, thereby making them verifiable and trusted. Brazil achieved almost universal coverage of bank accounts by the mid-1980s, thereby creating a large user base that is conversant with financial payments. Similar to India, Brazil's Cadastro de Pessoa Fisica (CPF) facilitates authentication for financial transactions and is embedded in almost all registries, both public and private.

Second, regulatory institutions play a key role in ensuring that the new digital payment systems are accessible, convenient, and trusted. As Brazil and India became more digitized over the last decade, the digital payments ecosystem leveraged the expansion of fast and reliable data networks, as well as mobile phone penetration, across all segments of the population. While a negligible transaction fee mandated by BCB and NPCI has often been cited as a key factor for the rapid growth of the two platforms, the experience of Brazil and India also shows the impact of design choices (such as QR codes and voice-based interfaces) that reduce barriers for users, especially for those who are new to the digital payments ecosystem. One key lesson from this is that countries seeking to adopt new digital payment systems need to balance regulation with innovation, ensuring that they are inclusive and adaptable to the needs of the expanding and evolving digital economy.

Third, digital payment platforms built on the principles of DPI — openness, interoperability, and trust facilitate both adoption and usage at scale. As we have outlined in Section III, both Pix and UPI constitute the payment layer in the DPI Stack, leveraging both digital ID and existing data exchange protocols. Through their rapid adoption and usage, Pix and UPI demonstrated both the market making and market shaping power of the DPI approach. Brazil and India have chosen open standards and protocols to enable both the public and private sectors to connect to digital payments gateways managed by trusted entities. They not only set the regulatory framework but also actively invested in the foundational technology (Bharat Interface for Money, or BHIM, was the first downloadable UPI application), thereby ensuring that these systems are country-owned and managed.

For other countries of the Global South to follow this path, the overarching lesson from Pix and UPI is that it is possible to build an inclusive, scalable, and efficient digital payments ecosystem if there is a clear public purpose, willingness to invest in digital public infrastructure, and adequate state capacity to guide policy, regulation, and implementation.

As digital payments become a critical enabler for an inclusive digital economy, there is an emerging discussion on whether the Pix-UPI model can become an alternative cross-border payment mechanism. In 2023, Brazil’s Central Bank initiated a pilot with India’s UPI marking the first steps toward a bilateral real-time payments system, potentially setting the stage for future integrations across Latin America, as well as with Europe, Middle East, Asia and Africa. However, this would require sustained cooperation among countries to align regulations, ensure interoperability, and harmonize data-sharing protocols. Creating such coordination mechanisms would catalyze the diffusion of the PixUPI model among countries of the Global South, enabling them to reap the benefits of a digital payments ecosystem that leaves no one behind.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Kamya Chandra, Tanushka Vaid, and Jeffrey D. Bean for their review of an earlier draft of this paper. This background paper reflects the personal research, analysis, and views of the authors and does not represent the position of the institution, its affiliates, or partners.

Cover image courtesy iStock user shut up.

Note: Citations and references can be found in the PDF version of this paper available here.