Special report no. 8

BY DHRUVA JAISHANKAR, AMMAR NAINAR, AND DAVID VALLANCE

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

China is undertaking a rapid expansion and modernization of its People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and is adopting a more assertive military posture, with implications for the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific. The United States is urging allies and partners to burden-share, including through contributing to crisis scenarios, improving their self-defense, and supporting regional security missions. This report assesses the capabilities and posture of 14 maritime powers in the Indo-Pacific and concludes that most U.S. allies and partners are already contributing more to their self-defense; that the Quad countries and France are contributing disproportionately to regional security missions; but that no Indo-Pacific power has the capabilities to substitute for the United States in a Taiwan-related military scenario.

In the future, most Indo-Pacific partners and allies of the United States will have to prioritize defense spending and invest in their defense industrial bases. They must also improve their capabilities in naval aviation; long-range strike; expeditionary forces; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); spacebased assets; and unmanned and autonomous systems.

I. THE BURDEN-SHARING CHALLENGE IN THE INDO-PACIFIC

While the world may be preoccupied with conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, China is preparing for war in the Indo-Pacific. The Indo-Pacific region is home to the largest concentration of the world’s population, several large and dynamic economies, and major military and nuclear powers. China’s rapid economic rise has been accompanied by one of the largest and fastest military modernization efforts in history. This has included the rapid expansion and modernization of its People’s Liberation Army Navy, which has commissioned new aircraft carriers, boasts a growing submarine fleet, and has demonstrated enhanced amphibious landing capabilities. China has also expanded its medium-range ballistic missile and intermediate range ballistic missile capabilities, invested in hypersonic missiles and new delivery systems, hardened shelters for aircraft and missile silos, expanded its maritime militia, and rapidly grown its nuclear weapon arsenal. It has developed asymmetric capabilities, incorporating new technologies such as large unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs), drones, electronic countermeasures, and cyberwarfare systems. Many of these new capabilities were on display at the 2025 Victory Day Parade in Beijing, one of China’s largest military parades in recent years. As part of these extensive military modernization efforts, China has established a significant defense industrial base. It has also developed a considerable merchant marine fleet and a network of potentially dual-use port and infrastructure facilities in the Indo-Pacific and beyond (in the Atlantic and Arctic oceans) to ensure supply security for withstanding a protracted conflict. Recent political purges at the senior-most leadership levels of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) offer a conflicting picture about the institution’s preparedness for war. Nonetheless, China’s paramount leader Xi Jinping has repeatedly emphasized combat readiness, technological solutions, and civil-military fusion in his quest to turn the PLA into a “world-class military.”

China's military intentions have also assumed a more assertive character. The country has expanded the scope and sophistication of its military exercises around Taiwan, which started in December 2025. The PLA Air Force and PLAN have attempted to intimidate Japanese military aircraft and naval vessels of the Philippines in the South China Sea. Using military as well as law enforcement and nominally civilian assets, China has continued to consolidate control of important waterways and airspace over these waters. Its recent aggressive actions in the Yellow Sea have also affected South Korea, while its development of military and dual-use infrastructure in the Himalayas continues to threaten the territoriality of India and Bhutan. The United States—long the Indo-Pacific region's preeminent military power—assesses China's intentions to be clear: to dominate the Indo-Pacific littoral, weaken U.S. alliances, reunify with Taiwan, and ensure political and economic dominance across the region. A particular focus will be on the first island chain, which links the archipelagos of Japan, the Ryukyu islands, Taiwan, and the Philippines. Much of China's military buildup can be characterized as part of a counter-intervention strategy, aiming to make support for Taiwan so costly that no country would attempt it. Thus, this theater remains the primary area from which China seeks to displace the United States. Successfully doing so would complete what Xi calls "the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation."

While acknowledging China's preparations to use force to alter the regional balance of power, the United States has long been advocating for greater military burden-sharing: the "the effective sharing of responsibilities, risks and benefits" among allies and partners. In practice, burden-sharing could refer to (i) contributing capabilities relevant to crisis scenarios or conflicts, (ii) contributing more to one's own self-defense, or (iii) contributing more to regional security in peacetime, such as counter-piracy missions or humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR). To these ends, the United States has been urging allies and partners to take greater responsibility for their own national or regional security needs without financial or military assistance from the United States." The Donald Trump administration, in particular, is motivated by a renewed focus on homeland security and the western hemisphere. "The days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over," the 2025 U.S. National Security Strategy states. "[S]ophisticated nations...must assume primary responsibility for their regions... The model will be targeted partnerships that use economic tools to align incentives, share burdens with like-minded allies, and insist on reforms that anchor long-term stability... The United States will stand ready to help—potentially through more favorable treatment on commercial matters, technology sharing, and defense procurement—those counties that willingly take more responsibility for security in their neighborhoods and align their export controls with ours.

Burden-sharing looks different in the Indo-Pacific context, compared to the United States' expectation of North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies in North America and Europe. The differences are a product of the "hub and spoke" alliance structures in the Indo-Pacific (in contrast to collective defense in Europe), the existence of non-allied partners (such as India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Singapore), and the peacetime competition underway with China (in contrast to the active conflict involving Russia in Ukraine). In practice, the United States has encouraged Indo-Pacific allies and partners to increase their defense spending, tighten and align their export controls, and commit to employing military assets in various contingencies. At the same time, the recent postponement of a 2+2 dialogue between the United States and Japan, a review of the AUKUS arrangement with Australia, and differences within the Quad (especially between India and the United States) have raised questions about the United States' reliability and commitment to Indo-Pacific security. Burden-sharing also looks different in the contexts of immediate conflict (as over Taiwan or in the South China Sea) and in peacetime (as in the Indian Ocean or South Pacific). But in each instance, burden-sharing requires an alignment of interests, credible capabilities, and political will.

The prospect of a more recessed U.S. posture in the Indo-Pacific has tremendous implications for the regional balance of power. For now, the United States retains a commanding military presence in the Indo-Pacific. The U.S. Pacific Fleet has 150,000 personnel—larger than most Indo-Pacific navies and access to overseas bases in the Philippines, Japan, Australia, and South Korea. The United States also has unique capabilities and scale when it comes to nuclear submarines, naval aviation, expeditionary forces, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) systems, making it indispensable to Indo-Pacific allies when it comes to certain aspects of maritime security. Despite political ambiguity, the U.S. military leadership and intelligence community continue to perceive the Indo-Pacific as a "priority theater" and China as the pacing challenge. In recent years, the United States took steps to counter China's increasingly sophisticated anti-access/area denial (A2AD) strategies in the first island chain, including investments in long-range strike; undersea, cyber, and autonomous capabilities; and investments in the modernization of nuclear and delivery systems. The United States also worked to increase the capabilities of allies and partners, through new coalitions and defense co-development and co-production. Some efforts were made at hardening bases in Japan and attaining access to new facilities in the Philippines, Australia, and Papua New Guinea. But U.S. efforts at keeping pace with China’s military modernization have been relatively slow: Budgetary commitments, export controls, and legacy hardware often prove difficult to overhaul. The United States has also struggled to simultaneously prepare for active conflict scenarios, gray zone tactics, and protracted conflict in the Indo-Pacific.

These twin factors—China’s growing capabilities and assertiveness, as well as increasing concerns about a recessed U.S. military commitment—have raised crucial questions for the Indo-Pacific’s other maritime powers. How much more should they be spending on maritime security, whether against state or non-state actors? What kinds of military assets should they be investing in as part of their modernization efforts? How can they best leverage their geographical advantages? Moreover, what are their current contributions to burden-sharing in the Indo-Pacific, whether in an active conflict scenario (e.g., involving Taiwan or the South China Sea) or during peacetime military competition? Where and how can they play a greater role? Variations of these questions are being considered by a host of regional actors, not least other countries that constitute the Quad; South Korea and Taiwan; Southeast Asian states; and European maritime powers, such as France and the United Kingdom. A systematic comparison of current maritime capabilities and posture can offer important insights as they contend with these questions.

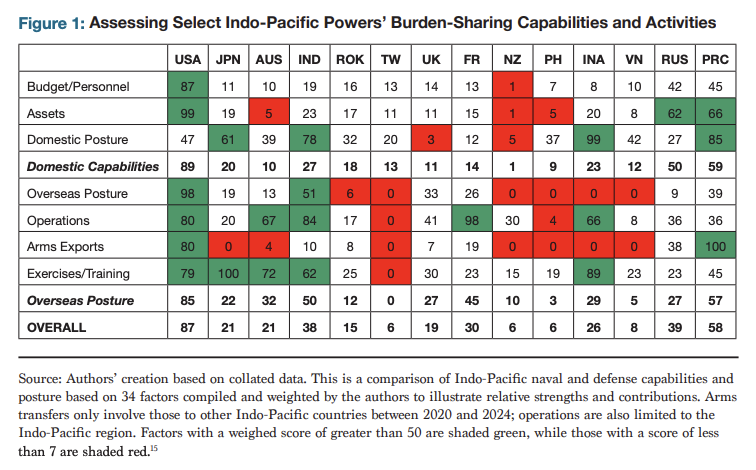

II. ASSESSING MARITIME SECURITY CAPABILITIES AND POSTURE

To assess comparable capabilities and activities in the Indo-Pacific, we compiled reliable and open-source information on the domestic maritime capabilities and overseas maritime postures of 14 Indo-Pacific maritime powers. These included the Quad partners (the United States, Australia, India, and Japan); U.S. allies (South Korea and the Philippines); European countries with significant regional military assets (France and the United Kingdom); large Southeast Asian states involved in the South China Sea (Indonesia and Vietnam); New Zealand, Taiwan, China, and Russia. To compare domestic capabilities, we examined defense budgets and naval personnel (Budget/Personnel); the number and nature of these powers’ submarines, surface combatants, naval aircraft, and expeditionary forces, as well as maritime domain awareness capabilities (Assets); and geographical advantages in terms of the number and location of their operational bases, air stations, repair facilities, and logistics depots (Domestic Posture). To compare overseas postures, particularly for out-of-area contingencies, we collated data on overseas bases and logistics arrangements (Overseas Posture); naval patrols and operations (Operations); defense exports (Arms Exports); and military exercises and training programs (Exercises/Training). Overall, we compared 34 key indicators of maritime capabilities and posture, compiling information on about 155 military exercises, over 240 naval operations, and 400 military sites and facilities across the Indo-Pacific. These quantitative factors were then weighted to illustrate relative strengths and vulnerabilities of different maritime powers in the Indo-Pacific (see Figure 1). Intangibles such as qualitative factors, untested technologies, and operational readiness could not be fully captured in such as assessment.

Such a comparative analysis draws attention to a few critical factors:

The United States retains a commanding lead as a maritime power in the Indo-Pacific in many respects, and benefits from high defense spending, arms sales, and an active network of overseas military bases. Its primary challenges are geographic, offset partly by its presence in Guam, Hawaii, and other Indo-Pacific territories, and the emergence of a near-peer competitor in China.

China's rising military assets and arms exports are indicative of its growing defense industrial base. (Its defense exports in the Indo-Pacific are somewhat inflated by considerable arms transfers to a single country: Pakistan.) However, while China's overseas posture, military operations, and exercises and training efforts may appear modest compared to the United States and others, they have been growing in line with its capabilities.

The United States' Quad partners already make significant contributions to out-of-area peacetime burden-sharing in terms of maritime operations and exercises and training. Much the same can be said for the United States' European allies (France and the United Kingdom) and Indonesia. Japan, India, and Indonesia are also vitally important for the United States from a geographic perspective. However, while South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Vietnam haveincreased burden-sharing in terms of their self-defense capabilities, their contributions to out-of-area security activities remains more limited.

At the same time, most U.S. allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific have underdeveloped defense industrial bases. This is indicated by their relatively meager budgets, personnel, naval assets, and exports. While important investments are underway (such as Japan’s fighter aircraft and submarine development, Australia’s efforts within AUKUS, and India’s growing defense exports), U.S. allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific can still make greater contributions in these areas. In some cases, defense exports have traditionally been politically inhibited, as in Japan by its pacifist legacy and in Taiwan by its lack of diplomatic recognition.

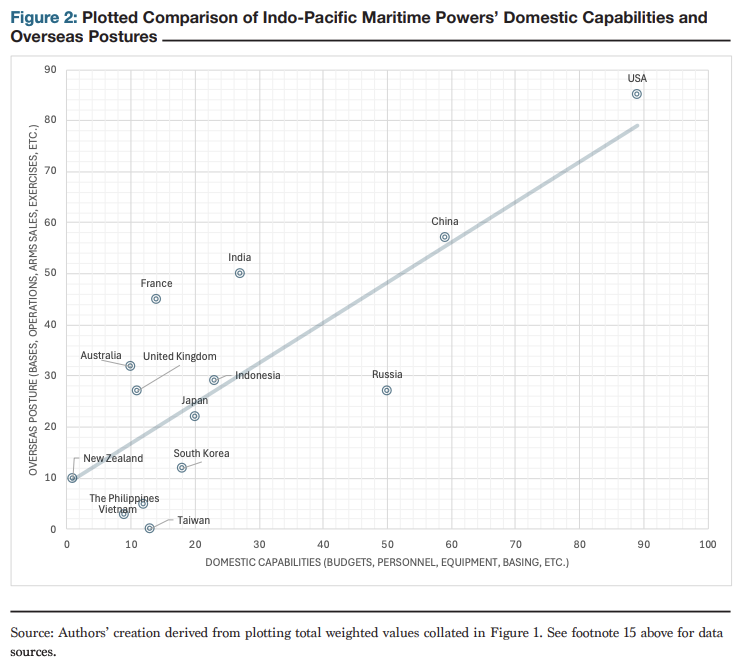

Comparing the domestic capabilities and overseas posture of various maritime powers (see Figure 2) also helps illustrate which states are contributing more to out-of-area regional burden-sharing in the Indo-Pacific relative to their domestic capabilities. India, Australia, France, and the United Kingdom, for example, are more actively involved in overseas maritime activities than commonly appreciated. By contrast, South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Vietnam are more focused on proximate military threats rather than out-of-area contingencies and overseas partnerships. On the flip side of the coin, countries like India, Australia, and France might be underinvesting in their domestic foundations of naval power relative to their extensive overseas commitments, suggesting their personnel and assets are more thinly stretched.

Source: International Energy Agency, “Sources of global electricity generation for data centres, Base Case, 2020-2035,” International Energy Agency, April 2025. License: CC BY 4.0.

III. IMPLICATIONS FOR INDO-PACIFIC MARITIME POWER

The Quad (Australia, India, and Japan)

The focus of maritime burden-sharing efforts in the Indo-Pacific is likely to fall heavily on the United States' Quad partners. The Quad has emerged as a loose coalition of four Indo-Pacific maritime powers (Australia, India, Japan, and the United States). Of these, Japan and Australia are U.S. treaty allies with treaty obligations and high levels of military integration and interoperability. India has no mutual defense arrangement with the United States: it hosts no U.S. bases or troops, it receives no U.S. military aid, and it has an independent nuclear deterrent capability. But all three of the United States' Quad partners are capable maritime states with similar threat perceptions despite distinct geographic, economic, and political circumstances.

Australia boasts a continent-sized geography and an incredibly long coastline. It is also a resource-rich and trading economy, dependent on the free flow of maritime commerce to markets in Asia and beyond. It currently has a small but robust military force, including a naval component. This currently includes 11 surface combatants, six submarines, and two assault ships, six diesel-electric submarines, as well as numerous smaller patrol boats, minesweepers, and support ships. As part of a surface fleet review, the Australian navy expects to acquire frigates from Japan, develop autonomous systems such as the UUV Ghost Shark, and benefit from the British Type 26 frigate design for a future "tier one" surface combatant. AUKUS Pillar I involves plans to rotate American and British nuclear-powered submarines through Australian ports, prior to Australia's acquisition of at least three Virginia-class submarines, and before the future SSN-AUKUS can be designed and manufactured. Nuclear propulsion improves the reach of Australia's submarines and assists with consistent deployment and interoperability. Meanwhile, cooperation under AUKUS Pillar II, as on quantum technologies and advanced cyber, can help prevent communication sabotage, while collaboration on hypersonic and counter-hypersonic weaponry will enhance the strike and defensive capabilities of AUKUS countries.

Australia's defense forces have nonetheless proven themselves important and active partners in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) missions, including in the South Pacific, in maritime surveillance out of Butterworth in Malaysia, and through sustained regional presence deployments throughout the Indo-Pacific. Cooperation with Quad partners, particularly Japan and India, has increased with the conclusion of a reciprocal access agreement with Japan and the initiation of military staff talks with India, as well as regular naval exercises with all Quad partners. Nonetheless, Australia faces challenges including a relatively small industrial base, which is difficult to scale, defense industrial workforce shortfalls, insufficient naval budgets, and struggles with military recruitment. Despite government commitments to raise spending, it is not clear how quickly Australia will be able to do so without creating inefficiencies and waste. Starting in July 2026, a new agency, the Defence Delivery Agency, will attempt to address these issues.

The military contest between the United States and China is also shaping India's strategic environment. China's development of port investment in several Indian Ocean littoral states, its high level of military support to Pakistan, and its sale of military assets to Bangladesh and Myanmar have contributed to Indian concerns. Furthermore, India's dependence on maritime trade through the Indian Ocean is considerable, particularly for energy and other vital commodities. The growing challenge of non-state actors, such as pirates and Houthi rebels in Yemen, have further added to India's maritime threat environment. The Indian Navy's stated objectives are to deter conflict and coercion against India, safeguard India's seaborne trade and imports, and stem the flow of seaborne threats against India's citizens, homeland, and offshore assets.

India's burden-sharing tradition goes back to its military engagements and cooperation with Indian Ocean and Southeast Asian states in the 1990s. In the early 2000s, the Indian Navy escorted U.S. vessels through the Malacca Strait after the September 11 terrorist attacks and coordinated with the United States, Japan, and Australia in tsunami relief operations in 2004 and 2005. Following China's deployment of PLAN vessels in the Indian Ocean after 2008, India's maritime security efforts have stepped up, and they became more structured and systematized in 2017, following the Doklam border crisis with China. The Indian Navy has since deployed on a permanent basis across the Indian Ocean—from the Gulf of Aden and Exclusive Economic Zone of Mauritius to the Bay of Bengal and Strait of Malacca. 20 It also regularly sends vessels east of the Malacca Strait for military exercises, patrols, port visits, and HADR missions. For example, within the past year, the Indian military has exercised off Guam and South Korea and contributed to maritime domain awareness through the Quad's Indo-Pacific Maritime Domain Awareness initiative. Cooperation with the United States has deepened over the past two decades and defense cooperation has continued despite political turbulence in 2025. India now participates in Combined Maritime Forces operations with the United States and partners in the Indian Ocean. But it also continued to diversify its partnerships in 2024 and 2025, including a joint declaration on security with Japan that pledged deeper technological, logistic, special forces, and ship repair cooperation. India and the Philippines recently declared a strategic partnership with a defense, security, and maritime focus. A new defense dialogue with New Zealand and port visits to Fiji and Papua New Guinea are other demonstrations of India's commitment to Indo-Pacific security. It has now developed an extensive network of operational turnaround points that enable the Indian Navy to operate from the eastern seaboard of Africa to the South Pacific and South China Sea. Efforts have also been made to improve coast guard cooperation with the United States and other partners and facilitate logistics and transport.

India strives for a balanced force structure of 200-230 ships capable of persistent operations across the Indo-Pacific, while increasing its reach and sustenance. It is also focused on indigenizing its defense industry to become less reliant on imports. To this end, India is developing next-generation surface vessels, amphibious transport docks, and another aircraft carrier. Its submarine fleet remains relatively small, with a mix of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines and diesel-electric submarines (nuclear-powered attack submarines have traditionally been leased from Russia), although a new submarine base will soon be inaugurated on India's east coast. India has also made further investments in coastal defenses, which increased after the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks, and is developing unmanned systems. Nonetheless, challenges remain. The Indian navy still receives a smaller proportion of the defense budget than it desires. Although about 50 vessels are under construction in Indian shipyards, there are challenges related to timelines for delivery. India also remains dependent on foreign suppliers for engines and space-based navigation, and its research and development infrastructure remains insufficient. Furthermore, arrangements for ship repairs and maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) have not been fully leveraged, including by its partners.

Japan, being an archipelagic state, sees its security primarily in maritime terms. Although long invested in the U.S.-Japan alliance and having a pacifist orientation, it has gradually evolved into a more independent and capable security actor. These steps were driven in no small part by an increased threat perception from China after a spike in tensions over the disputed Senkaku Islands (which China calls the Diaoyu Islands) between 2010 and 2013. Japan also had increased concerns about China's development of military and dual-use infrastructure, including undersea cables and ports. Under former prime minister Shinzo Abe's government, Japan created a National Security Council, formulated a National Security Strategy and National Defense Program Guidelines, and created an Acquisition, Technology and Logistics Agency for defense research, development, and procurement between 2012 and 2015.

There is a growing understanding among Japanese leaders that the country will be involved in a Taiwan-related contingency, not least because of the presence of U.S. troops in Okinawa and the Japanese mainland, as well as the proximity of several Ryukyu islands to Taiwan. Recent statements by Japan's Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi that a Chinese naval blockade on Taiwan would constitute a "survival-threatening situation" and require the mobilization of Japan's Self Defense Force only make explicit what several of her predecessors had acknowledged. The Japanese government has more recently committed to a drastic increase in defense spending and investment in long-range strike capabilities. It is also developing hypersonic and anti-ship missiles and is deploying them on island territories. Nonetheless, further steps will be required to develop independent military capabilities, including intelligence and space-based assets. Military recruitment and retention are also complicated by Japan’s aging population and vestiges of pacifism in Japanese society. Additionally, Japan’s proximity to China changes its threat perceptions relative to other Indo-Pacific countries, which may form a barrier to deepen coordination on burden-sharing.

Other Maritime Powers: South Korea, Southeast Asia, and Europe

Other Indo-Pacific powers beyond the Quad confront similar questions about bur-den-sharing. South Korea retains a potent military force with a large economy, high levels of defense spending and operational readiness, and boasts a strong and capable defense industrial and shipbuilding base. But it has historically been focused on contingencies related to North Korea. Questions of U.S. credibility and concerns about the security of maritime trading routes have contributed to a gradual focus on a broader Indo-Pacific region. China's encroachment into South Korea's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and air defense identification zone have accompanied periodic increases in tension with Beijing, which spiked after the deployment of the U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system in 2017. Consequently, Seoul is investing in greater blue-water naval capabilities and ISR systems. It has also diversified its partnerships, including by consolidating the U.S.-Japan-South Korea trilateral partnership on missile defense and anti-submarine warfare. It has increased its defense exports to India and Southeast Asia, but has a more limited role to play in contingencies related to Taiwan, the South China Sea, and the Indian Ocean.

Meanwhile, in Southeast Asia, the two states most heavily invested in disputes with China in the South China Sea are the Philippines and Vietnam. Unlike Indonesia or Malaysia, public sentiment in these countries perceive China in competitive terms, as reflected in public opinion surveys. The Philippines benefits from a U.S. alliance that has strengthened in recent years and enjoys consolidated relationships with Japan and Australia. It has also made major strides in its maritime security capabilities over the past decade, albeit from a low base. It has also invested in better maritime domain awareness based on remote sensing, commercial platforms, and satellites in low Earth orbit. A 15-year armed forces modernization program is underway and has benefited from the acquisition of cruise missiles from India, coast guard vessels from Japan, and frigates from South Korea. These and related steps have enabled better patrolling of the Spratly Islands and Scarborough Shoal.

For its part, Vietnam has invested in a capable maritime fleet focused on coastal defenses. At the same time, it has limited undersea capabilities with a more antiquated Kilo-class submarine fleet. (India has provided some submarine training.) Russia remains a significant provider of defense equipment to Vietnam, although Japan is providing new ships, and the United States has explored the possibility of selling transport aircraft. Overall, Southeast Asian disputants in the South China Sea have had more success in deterring further Chinese revisionism since 2021, notwithstanding more recent collisions in Scarborough Shoal and tensions over the Second Thomas Shoal.

European states are also increasingly invested in and interested in the Indo-Pacific, for more than political and economic reasons. The intensifying China-Russia partnership and the deployment of North Korean soldiers in Ukraine have contributed to European interest in the security of the Indo-Pacific. France and the United Kingdom have permanent footprints in the Indo-Pacific and force projection capabilities. France has articulated an Indo-Pacific strategy, having 2 million citizens and 7,000 permanent troops in the region as well as an extensive EEZ. In addition to territories such as La Reunion and New Caledonia, France has bases in Djibouti and the United Arab Emirates. It maintains two frigates each in the Indian and Pacific Oceans as well as patrol vessels and maritime surveillance aircraft. It is also a major arms supplier to the Indo-Pacific, including Rafale fighter aircraft and Scorpène-class submarines, and has invested in resilience of critical infrastructure including cybersecurity and subsea cables in the region.

While most Indo-Pacific maritime powers are enhancing their burden-sharing abilities through increases in defense spending, military procurement, diversifying partnerships, and changes to posture—and the trendline is broadly positive—it may not be fast enough to avert certain scenarios. It is also not a foregone conclusion that regional powers would see their interests aligned to a high enough degree to, in the event of a more recessed U.S. presence in the Indo-Pacific, make up for that shortfall. Nonetheless, motivated primarily by their own territorial concerns and national interests, most Indo-Pacific powers are taking steps to contribute more to their and their region's maritime security. This could well make a difference in the event of greater tensions involving China in the East China Sea (as over the Senkaku Islands), in the Yellow Sea (involving South Korea), in the South China Sea (involving the Philippines, Vietnam, or other claimants), and in the Indian Ocean (involving India, France, Australia, and possibly others).

However, barring Japan and possibly the Philippines due to the proximity of Luzon, the burden-sharing efforts of the United States' many Indo-Pacific allies and partners are unlikely to make a meaningful difference in any Taiwan-related contingency beyond intelligence, logistics, and support. In the event of a Chinese naval blockade on Taiwan, cross-Strait amphibious invasion, or gray zone operation (as against Kinmen), no U.S. ally or partner would be able to operate fully independent of the U.S. military. 32 While the forceful reunification of Taiwan by the People's Republic of China would have profound effects on the balance of the power in the Indo-Pacific, legal, political, and military factors would constrain the ability of the United States’ Indo-Pacific allies and partners to play a more active role in any kinetic contingency. If Taiwan remains the most likely and most consequential potential flash point in the Indo-Pacific, an outcome to any kinetic action is still likely to depend largely on the United States’ preparedness and willingness to be involved.

IV. CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The broad overview of China’s military modernization and intentions, the United States’ changing priorities and commitments, the perspectives and strategies of other Indo-Pacific powers, and these maritime powers’ capabilities and postures carries several implications:

First, China continues to seek maritime dominance in the Indo-Pacific, including preparations for a forceful takeover of Taiwan, displacement of the United States from the first island chain, and control over key sea lines of communication.

Second, the United States and China retain a commanding lead when it comes to defense budgets, military capabilities, and defense industrial bases, relative to other maritime powers in the Indo-Pacific. This gap is considerable, despite nascent but important steps taken by India, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and others to increase spending and invest in defense industrial production and exports.

Third, India, Australia, and Japan already play a major burden-sharing role in terms of out-of-area peacetime operations. India and Australia, in particular, contribute disproportionately to regional security relative to their capabilities, as do countries like France, the United Kingdom, and even New Zealand (in the South Pacific).

Fourth, despite having more limited out-of-area capabilities, South Korea and Taiwan have considerable defense industrial and technological strengths that can contribute to their self-defense against proximate military threats, while the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia enjoy important geographical advantages that are often overlooked.

Fifth, these efforts at burden-sharing could have important (and, from the United States’ standpoint, positive) long-term implications for peacetime security competition in the Indo-Pacific, including by deterring or complicating Chinese assertiveness and revisionism in the Indian Ocean, South China Sea, East China Sea, Yellow Sea, and South Pacific.

Finally, ongoing and potential burden-sharing efforts on the part of U.S. allies and partners in the Indo-Pacific are unlikely to replace the role of the United States in any Taiwan-related conflict scenario.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the participants of a two-day workshop on Indo-Pacific maritime security held in Washington DC in late 2025 for their insights and inputs. They also thank Lindsey Ford and one anonymous reviewer for their valuable feedback, as well as Arthur Hur for his edits. Any errors that remain are the authors’ alone.

Cover photo courtesy iStockphoto user Dovapi.

Note: Citations and references can be found in the PDF version of this paper available here.