Special Report No. 6

Authors: Medha Prasanna, Caroline Arkalji, and Hansika Nath

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

India, Brazil, South Africa, and Indonesia are among the most prominent proponents of the Global South, spearheading substantial reforms in climate action within the global governance architecture through platforms such as the G20, the India, Brazil, and South Africa initiative (IBSA), BRICS+, and multilateral development banks (MDBs). The energy transitions of these countries and their partners are critical to global emissions reductions. Collectively, these countries represent nearly 25 percent of the global population and 12 percent of the global emissions. Despite diverse contexts, these countries share similar challenges that can be effectively addressed collectively.

This special report outlines the challenges posed by legacy fossil fuel infrastructure, inadequate financial commitments, and reliance on concentrated supply chains. Together, these countries can strengthen their collective bargaining power, fortify institutional capacity to absorb climate finance, harmonize climate finance taxonomies, implement comprehensive strategies to phase out fossil fuels, create channels for sharing knowledge of best practices in climate finance deployment, and maintain long-term competitive advantage through clean industrial strategies.

I. INTRODUCTION

India, Brazil, South Africa, and Indonesia are regarded as the emerging powers in the developing world, or what some have termed the Global South. Founded in 2003, the India-Brazil-South Africa, or IBSA, initiative provided a forum to promote development cooperation and knowledge sharing among the three largest democratic developing economies across Asia, Latin America, and Africa. The four countries are members of the G20, where they have held consecutive presidencies starting with Indonesia in 2022, leveraging the opportunity to put energy transition as a key priority for the G20. In 2025, Indonesia joined the expanded BRICS as a full member, providing another platform where the four countries can collaborate to advance the goals of energy transition, building on the lessons from their G20 presidencies.

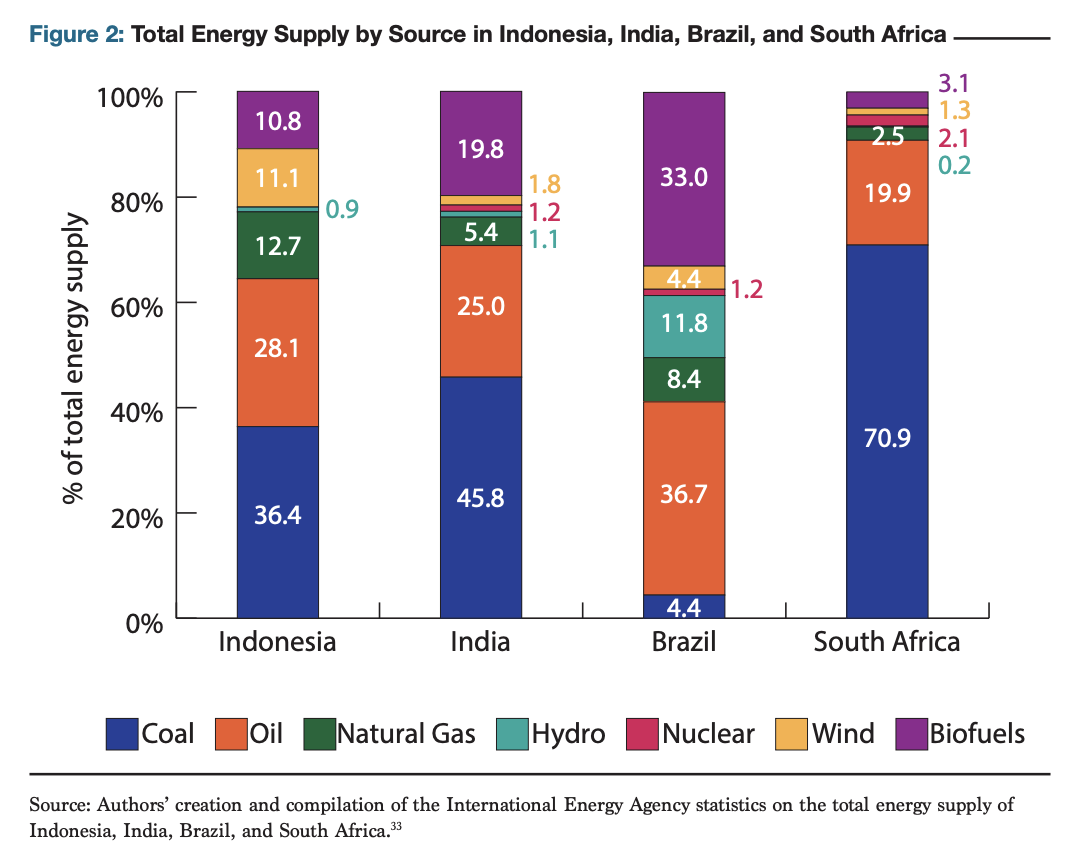

This special report explores how an IBSA+Indonesia framework could alleviate constraints and address the shared challenges of energy transitions. Together, IBSA and Indonesia represent nearly 25 percent of the global population and 12 percent of global emissions. These countries have set ambitious targets to transition away from fossil fuels, but they face both distinct and common challenges in their energy transition strategies. Electricity demand is expected to increase by 38 to 55 percent by 2035 across the four countries, further complicating the challenge of reducing reliance on fossil fuels without compromising universal energy access. The diversity in energy profiles shapes each country’s energy transition pathways and constraints. Brazil’s relatively clean power sector (nearly 90 percent renewables) creates a strong foundation for renewables, but it is increasingly dependent on fossil fuels for transportation and other hard-to-abate sectors, such as steel. On the other hand, South Africa remains heavily dependent on coal, which accounts for over 70 percent of its total energy supply and faces the challenge of transitioning coal-dependent communities while maintaining energy security. India and Indonesia are gradually increasing renewable capacity, but must strike a balance between rapidly growing energy demand and efforts to decarbonize.

Despite their differences, all four countries share common challenges, including political and economic sensitivities, infrastructure gaps, and social equity concerns. They encounter significant climate finance gaps: developing countries, excluding China, will need an estimated $2.4 trillion annually by 2030 to achieve climate and development goals. Additionally, fragmented regulatory systems and reliance on foreign supply chains, especially China, which controls up to 90 percent of global clean tech manufacturing, create structural risks to energy security and long-term competitiveness. Effective energy transition strategies require coordinated, locally adapted policies, informed by the shared experiences of the Global South.

To identify areas of cooperation, Section II provides a brief overview of how IBSA and Indonesia are advancing their energy transition ambitions into practice. These countries are at different stages of integrating renewable energy into the energy mix, phasing out fossil fuels, and implementing industry-specific shifts. The phase-out of coal and oil from the energy mix touches sensitive issues surrounding countries’ employment footprint and is further deterred by steep increases in projected energy demand. Despite ambitious emissions reduction targets, these countries struggle to achieve cross-ministerial alignment that embodies whole-of-government efforts. This is crucial for ensuring clean energy access across diverse social groups and geographies, and more broadly, for achieving the dual goals of development and energy transitions.

In Section III, the discussion on climate finance highlights the twin crises of insufficient climate finance and insufficient institutional capacity to absorb funds. Additionally, inspite of the deployment of various climate finance instruments, there is a lack of coherence in the investment environment for both domestic and international participants. To solve these crises cooperatively, IBSA and Indonesia have a significant opportunity to harmonize climate finance taxonomies, share lessons learned from the deployment of climate finance instruments in similar environments, jointly strengthen the political and financial fluency of institutions, and elevate similar local initiatives for greater investor visibility.

All four countries heavily rely on external manufacturers, principally China and Europe, for key clean energy inputs. Section IV explains how access to critical minerals, grid modernization, storage, and emerging fuels (like green hydrogen) are becoming bottlenecks in energy transitions, especially as Global North countries pursue aggressive industrial strategies that disadvantage developing countries with limited capabilities to decarbonize. IBSA and Indonesia must limit their reliance on concentrated supply chains by adopting strategic clean industrial policies, as well as co-developing clean technologies of the future made by and for the Global South.

The final section recommends an IBSA and Indonesia framework that addresses the shared constraints of the energy transitions and foster long term competitiveness through alignment: facilitating collective bargaining of capital, developing clean technologies, building institutional capacity, enabling workforce transitions away from fossil fuels, and establishing effective clean industrial strategies.

II. ENERGY TRANSITIONS STRATEGIES

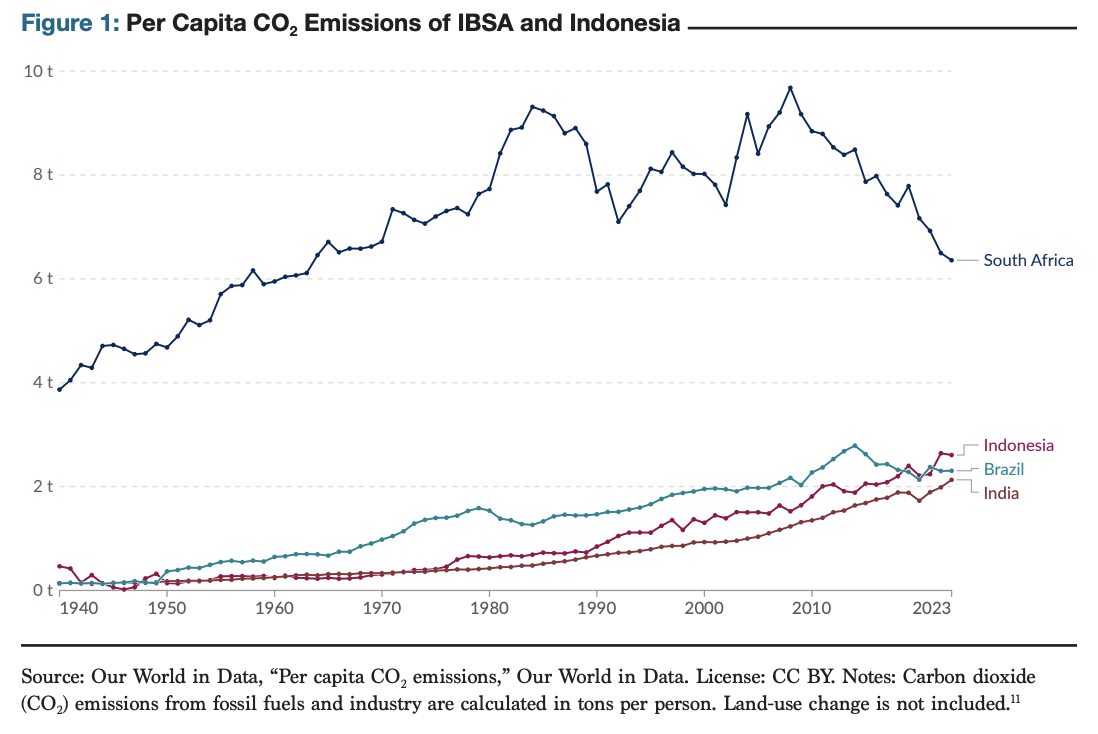

IBSA, the tripartite cooperative framework between India, Brazil, and South Africa, has had some success in poverty and hunger alleviation, access to life-saving medications, education, safe drinking water, and the development of biofuels. The initiative has also focused on funding projects led and driven by the Global South, and concurrently called for reforms in the international financial architecture. Indonesia shares in the legacy of ensuring Global South priorities remain a part of the global governance agenda, beginning with its founding membership in the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and its role in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). As of 2023, together IBSA+Indonesia represent nearly 25 percent of the global population, just over 7 percent of the global gross domestic product (GDP), and about 12 percent of global emissions (Figure 1), with expected increases in emissions till 2030 and a decline thereafter (Table 1).

Despite these successes, IBSA's role and impact have been eroded recently due to the emergence of competing groupings, most notably BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). Indonesia became a full member in January 2025, and along with Egypt, Ethiopia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Iran now form an expanded BRICS+ group. However, as some of the fastest-growing clean energy markets globally, IBSA+Indonesia offers opportunities for coordination and flexibility to pursue their shared agendas on just energy transitions that go beyond the limitations of groups like BRICS+.

Brazil has a clean electricity mix, which positions the country well to decarbonize its economy through electrification (Figure 2). In 2023, the share of renewables in the electricity mix reached 89.2 percent (49.1 percent of the total energy supply). Brazil's clean electricity mix has remained well above global levels, at over 70 percent, over the last 20 years. Since 2015, Brazil has become a net exporter of oil, consuming 50 percent of its total production. Conversely, it depends on natural gas (30 percent) and coal imports (80 percent). Brazil plans to phase out coal-fired power plants by 2040. Brazil's energy transition strategy (outlined in Table 1) emphasizes a broader economic-ecological approach that includes a strategy to promote sustainability through the use of biological alternatives such as bio-fuels rather than a conventional shift in the energy mix. In 2022, Brazil's Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) pledged to achieve net zero by 2050, with a 35 percent emissions reduction compared to 2005 levels by 2025, and 59 percent - 67 percent by 2030. Some of the hard-to-abate sectors, including aviation and steel, require different approaches.

South Africa's mitigation strategy involves a Peak, Plateau, and Decline (PPD) emissions trajectory that targets peak emissions in 2025, plateau through 2035, and absolute decline thereafter (Table 1). In its updated NDC, published in 2021, the country commits to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions further, a significant tightening from its initial targets (Table 1). However, as Figure 1 and 2 depict, coal accounts for a large part of South Africa's total energy supply, over 70 percent, making it one of the most coal-dependent countries in the world. It ascribes South Africa's high per capita emissions status, which is many magnitudes higher than India, Brazil, and Indonesia. This makes South Africa the least well-positioned to achieve its net-zero goals. Powerful historical and socio-cultural narratives surrounding the ownership of coal mines and the centralized electricity supply (approximately 90 percent) by Eskom, the state utility, have complicated South Africa's transition away from coal. The financial instability at Eskom, end-of-life coal deposits, infrastructure constraints, and the NDC goals have prompted the government to lead several initiatives aimed at creating a more pro-investment environment in South Africa. Furthermore, despite delayed delivery, the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) Investment Plan in South Africa is ambitious and expansive, targeting clean energy for electricity, clean energy vehicles, and green hydrogen.

India faces similar struggles in phasing out coal, which accounts for 45 percent of India's total energy supply (Figure 2). India's federalized electricity sector and coal's regional employment footprint heavily constrain reform. India has one of the most ambitious energy targets, aiming for net-zero emissions by 2070, and seeks to achieve 50 percent of its cumulative installed capacity from non-fossil sources, totaling 500 gigawatts (GW), by 2030 (see Table 1). As of July 2025, India achieved its 2030 target of 50 percent electrification from non-fossil fuel sources, 5 years ahead of set goals. India is growing its renewables capacity at the fastest rate among emerging economies. However, energy access is bifurcated, with large portions of rural and peri-urban populations relying on non-modern biomass. When faced with fragmented institutional coordination and state-level politicization, achieving clean energy targets and integrated energy access presents a significant challenge.

Indonesia's energy transition bottlenecks mirror IBSA countries in addressing captive coal use, transmission connectivity in remote areas, and equity concerns surrounding the costs of the energy transition. Indonesia's optimistic scenario envisions net zero emissions by 2060 (Table 1), with a 43.2 percent reduction by 2030. Indonesia's core decarbonization strategy involves the JETP. Despite the United States' recent departure from the JETP, Indonesia has signaled its intent to continue towards its commitments, with support from Germany, Japan, and several international organizations. In contrast to these developments and despite growing concerns about economic efficiency, construction of

coal power plants has continued, and fossil fuel subsidies remain politically sensitive and a socially embedded issue. The country is also increasingly turning to the United States and BRICS for liquefied natural gas and oil to secure its energy supply.

All four countries are pursuing ambitious energy transition strategies and goals, both domestically and through international platforms like the G20, BRICS, and the United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP). Table 1 details the latest NDC targets, where India, Indonesia, and Brazil pledge an immediate decline in emissions, and South Africa tries to balance its development targets with a PPD approach. Across the board, access to energy across social groups and geographies remains central to transition strategies but is met with significant challenges of cross-ministerial alignment, phasing out of fossil fuels, and projected peak energy demand outpacing emissions reduction targets.

III. CLIMATE FINANCE: LEADERSHIP, OPPORTUNITIES, AND CONSTRAINTS

The past few years have witnessed escalating military conflicts globally, leading to increased defense spending and reducing the fiscal space available for Global North and multilateral contributions to energy transitions. Reorienting climate finance systems to address these ambitious clean energy targets requires multilateral coherence and leadership from Global South countries to set norms that support just and equitable energy transitions. This section on climate finance explores IBSA and Indonesia's push for climate finance for the Global South through the multilateral processes, the role of international climate finance in achieving NDC targets, and the effectiveness of domestic climate finance vehicles and instruments.

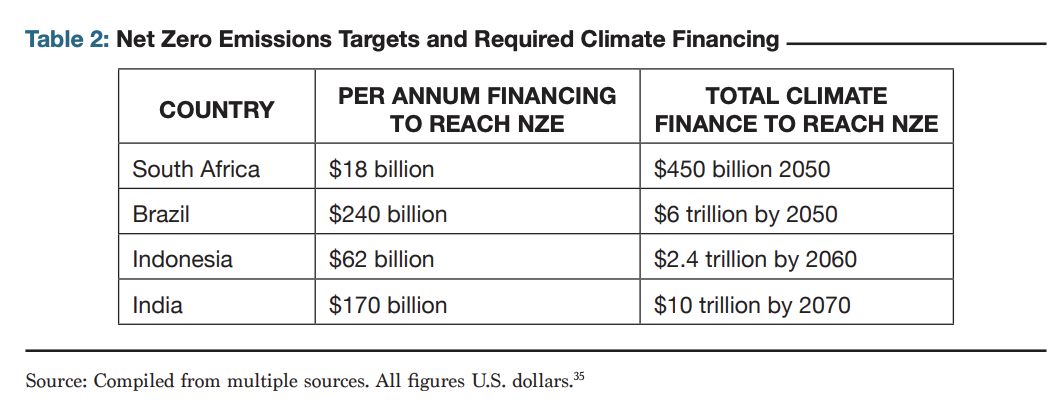

As a baseline, to get to net zero, an estimated $10 trillion by 2070 is needed for India, $6 trillion by 2050 for Brazil, $450 billion by 2050 for South Africa, and $2.4 trillion by 2060 for Indonesia (Table 2). At Azerbaijan's COP29, the new deal to provide developing nations with at least $300 billion a year and $1.3 trillion by 2035 fell short of the estimated climate finance for developing countries to meet their net-zero targets. Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) also fell short by reiterating previously set goals of $120 billion by 2030, instead of setting new targets. Despite limited commitments from traditional donors, these developments have shed light on the important role of non-traditional donors in this sector like the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states (especially Saudi Arabia) and BRICS countries. For instance, the $30 billion Alterra Fund, aimed at mobilizing climate-related investments, and Masdar, both launched by the UAE, are actively investing and entering joint ventures in Indonesia. Qatar's central bank has similarly been injecting large sums of climate finance and activating green bonds across Asia.

IBSA and Indonesia are attempting to attract private capital by offering attractive incentives, but the cost differential between multilateral and private financing is both substantial and unsustainable, making it difficult for private finance to fund the energy transition solely. Current climate finance mechanisms remain severely fragmented, burdened by conditionalities, and structurally unequipped to attract investment at the scale required for equitable transitions. For instance, Brazil will require an estimated $200 billion in investment to meet its 2030 climate goals, which is over $100 billion more than the country is currently projected to receive by 2030, ranking it as the seventh-highest climate investment gap globally and the second-highest among emerging markets outside of China. In South Africa, tracked annual climate finance averaged $7.4 billion during 2019-2021, a record high. However, this figure remains significantly below the estimated average annual requirement of $18.9-$30.2 billion to meet 2030 objectives, suggesting the need to increase flows fivefold (Table 2).

International Climate Finance

The past four Global South G20 presidencies have seen significant traction on climate finance through the Sustainable Finance Working Group (SFWG) and the Energy Transitions Working Group (ETWG). Indonesia's 2022 presidency set the agenda by identifying key pillars at the core of Global South energy transitions. India's presidency provided a platform for voices from the Global South by mainstreaming African challenges, the sustainable development goals (SDGs), and poverty in the G20 agenda. Brazil's presidency carried forward these initiatives and further anchored the G20 narrative of green transitions in development realities. This year, South Africa's message has maintained consistency by underscoring the need to scale energy transition investments globally by derisking private investment for climate change. A crucial omission, however, has remained: accelerating the transition away from fossil fuels. The G20 has served as an important platform for these four emerging economies to set norms for their needs and highlight climate financing gaps. It has introduced new targets and mechanisms for achieving them. However, these countries must now focus on implementing and operationalizing existing mechanisms that the G20 process has already delivered, rather than reinventing them.

Table 3 lists some of the most notable international climate finance partnerships, among them JETPs, green bonds, and national development banks offer essential insights into the role international finance plays in the energy transitions of IBSA and Indonesia. Insufficient funding is not the sole constraint. These countries also suffer from inadequate institutional capacity to absorb and deploy these funds.

The United States was one of the global leaders instrumental in securing JETPs for South Africa and Indonesia. While its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement (for a second time) and the JETPs have hurt the total international climate finance contributions, JETP host countries and their partners have remained steadfast in continuing the partnership and have invited other stakeholders to make up the difference. In both cases, withdrawal from JETP is of consequence from a symbolic standpoint, given the United States' influence over multilateral institutions. Substantively, the contributions primarily consist of loans through the United States Development Finance Corporation, which account for a minor share. In South Africa, German leadership has tried to mobilize other actors to close the gap, but the involvement of multiple institutions (about 50) and fragmented conditionalities make strategic coherence extremely difficult.

Indonesia JETP is far more reliant on the private sector than South Africa's, for nearly half of all contributions, anchored by the International Partners Group (IPG) and the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). Indonesia's and South Africa's institutional capacity to absorb these large funds, $8.5 billion and $20 billion, respectively, has been sluggish, due to the slow processing of bankable project proposals and delays in reforming key policies, and in turn, has failed to attract investors to close the gaps. A combination of both institutional capacity and committed investors is critical to making significant climate finance partnership agreements like the JETP work.

Green bonds can play a big role in mobilizing climate finance. IBSA and Indonesia have different strategies to issue them. India primarily relies on domestic issuance in rupees, with local banks and insurers serving as core investors. However, these bonds offer a lower green premium than the global average and offer no financial advantage over regular bonds, making them less attractive and India has struggled to attract both domestic and foreign participation. In contrast, South Africa and Brazil prioritize global issuance. South Africa's Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) issued a $235 million bond through private placement with a French development finance institution, Agence Française de Développement (AFD). This allowed South Africa access to a deep pool of international investors, potentially lowering capital costs but increasing dependence on foreign sentiment and exchange rate risks. Brazil released its Sovereign Sustainable Bond Framework in September 2023, shortly after which it debuted its sustainable bond. When released in November 2023, Brazil's $1.5 billion dollar-denominated bond saw 2.9 times oversubscription and was upsized to $2 billion. Like South Africa, Brazil, too, received access to new investors, although it shares similar foreign exchange risks. Indonesia offers a mixed model, with a domestic $1.25 billion Green Sukuk Bond and the world's first publicly offered sovereign international blue bond at $150 million through Japan. In this way, it balances both its local infrastructure and access to foreign capital. Overall, while global issuance offers larger, diversified funds, it introduces currency and external market vulnerabilities. A domestic strategy aligns with national priorities but can severely limit scale and investor diversity.

Beyond the JETP and green bonds, an essential international finance partnership vehicle is national development banks, which secure and channel concession finance. International experience, most notably from China, Japan, and Brazil's BNDES (Brazilian Development Bank), demonstrates the valuable role that public financial institutions can play in anchoring green industrial policy and scaling green lending (Table 3). These entities provide concessional credit, coordinate large-scale clean energy and industrial investments, and serve as institutional hubs for implementing climate strategies. In Brazil, for instance, BNDES not only channels concessional finance for sectors such as agriculture but also spearheads coordinated investment efforts through mechanisms such as the Amazon Bank Alliance and the Climate Fund.

Domestic Climate Finance Vehicles and Instruments

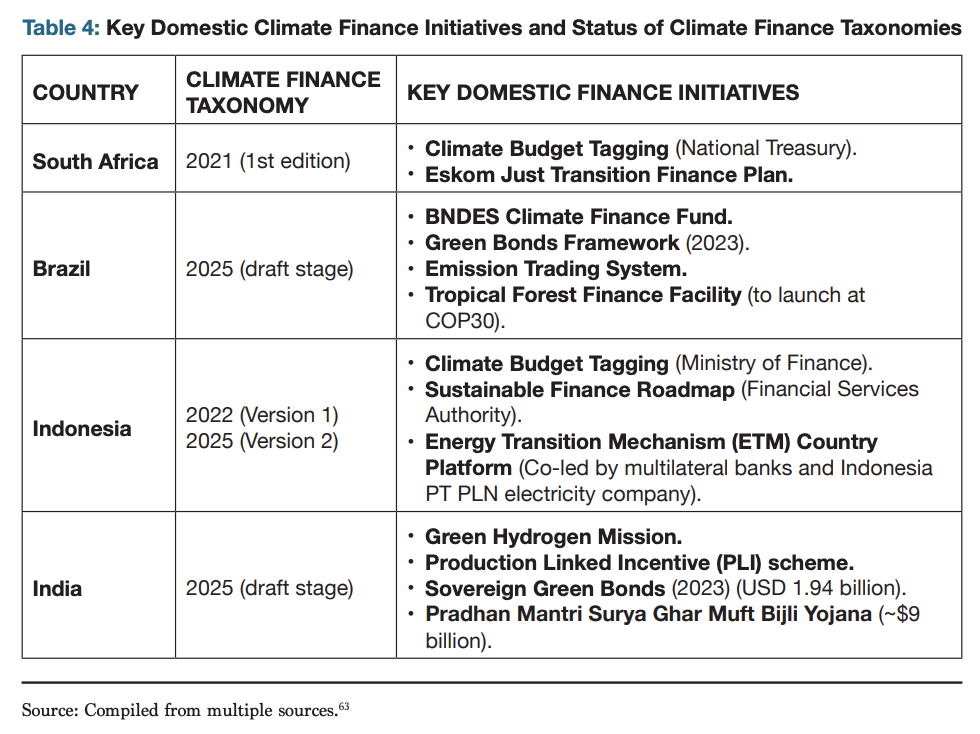

In response to investment gaps, countries in the IBSA + Indonesia grouping have been deploying industrial policies, taxonomies (a taxonomy is a classification system that defines and organizes economic activities based on sustainability criteria to evaluate their merit for government subsidies), as well as sector-specific and economy-wide climate finance instruments. These initiatives (Table 4) are increasingly translating into measurable domestic financial flows. India's tracked green finance in the fiscal year 2021-22 reached approximately $50 billion. Finance for mitigation was sourced predominantly through domestic channels, although there was a 2 percent year-on-year increase in international climate finance. Overall, finance flows to mitigation-related sectors rose by 20 percent during the same period.

In India, investment is driven by government-backed schemes and fiscal instruments, including the Payment Security Mechanism, Production Linked Incentives, and other targeted sector-level initiatives. In Brazil, the National Development Bank (BNDES) has sought to acquire equity stakes in companies to de-risk private capital flows into strategic sectors such as critical minerals, battery manufacturing, and electric vehicles. The bank has allocated approximately $1.6 billion in its acquisition budget for this purpose. The Brazilian government has introduced its industrial policy, "Brazil New Industry," which allocates about $60 billion to modernize the national industrial sector, focused on increasing autonomy and further developing clean energy sources. Complementing this effort, Brazil's Growth Acceleration Plan directs approximately $61 million, double from the 2020 allocation, toward mining-related research and development. Additionally, the Green Mobility and Innovation program provides more than $3.8 billion in tax incentives to encourage low-carbon automobile transformation.

Similarly, in Indonesia, policy frameworks such as the Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) and the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) are designed to mobilize private capital and accelerate the transition away from fossil fuel-intensive development.

Changes in electricity sector regulation have been a critical driver of growth in South Africa's climate finance landscape. These include the removal of licensing thresholds for new generation capacity, the development of wheeling and trading frameworks, and the declining costs of renewable technologies such as wind and solar. In parallel, the shift in market preferences, net-zero commitments by commercial financial institutions, and regulatory signals, such as the moratorium on new coal-fired power, have contributed to the realignment of investment strategies toward decarbonization.

IBSA and Indonesia are in different phases of publishing climate finance taxonomies to complement their clean industrial policies (Table 4). A climate finance taxonomy that provides clear definitions of green finance and climate finance and builds synergies with existing national goals can help reduce uncertainty and foster investor confidence, thereby facilitating the scaling of green finance and climate finance. The European Union's taxonomy has shown tangible outcomes over time, including higher volumes of aligned capital investments. However, interoperability and mutual legibility of taxonomies are crucial for scaling up green investments in the Global South. India and Brazil's proposed new taxonomies should be compatible with those of Indonesia and South Africa. Taxonomies must provide clarity, strict regulations, and penalties for institutions that fail to adapt. IBSA and Indonesia must share lessons learned from operationalizing taxonomies in similar contexts to further their energy transitions. For instance, Indonesia's land-use emissions are not being considered within current frameworks, despite their massive emissions profile.

Alongside industrial policy, taxonomy, and fiscal instruments, national public financial institutions are also emerging as essential enablers of climate-aligned investment. The structural bias of the global capital system continues to favor fossil fuel infrastructure, underscoring the need for systemic reform led by national platforms rather than fragmented, piecemeal efforts. A central pillar of such reform is the role of central banks in enforcing climate-aligned financial regulations. This includes implementing climate risk stress-testing frameworks and enforcing penalties for noncompliance, thereby aligning monetary stability with long-term decarbonization goals. In Indonesia, the experience of PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (PT SMI) further illustrates the potential of well-structured climate finance vehicles. Operated as a state-owned enterprise on a commercial basis, PT SMI combines sound governance and risk systems with project development expertise and the capacity to leverage private capital. Rather than establishing a new climate finance institution, the Indonesian government expanded PT SMI's mandate to include climate mitigation and adaptation, thereby capitalizing on existing institutional infrastructure and operational maturity.

Three lessons can be learned from PT SMI's institutional evolution. First, leveraging existing institutions, wherever feasible, can expedite the deployment of climate capital while maintaining alignment with national systems and standards. Second, strong and independent governance, supported by clearly defined investment mandates and comprehensive risk management frameworks, ensures discipline and credibility in financing decisions. Third, financial sustainability and leverage are essential to longevity. PT SMI maintains return hurdle rates, offers blended finance instruments such as investment grants to reduce capital costs, and preserves financial leverage without placing an undue burden on the state balance sheet. This climate finance vehicle design offers valuable insights for other developing and emerging economies aiming to scale climate action through financially resilient and institutionally anchored mechanisms. These institutional reforms operate in parallel with broader regulatory and market shifts that enable climate investment at scale.

Current trends highlight how these enabling conditions are translating into concrete shifts in sectoral financial flows. In India, foreign direct investment in the renewable energy sector has multiplied eightfold from FY 2021 to 2025. This surge is driven by large grid-scale solar projects as well as government-subsidized initiatives such as small solar power plants, solar pumps for agriculture, and rooftop solar systems. Tracked climate finance flows to electric vehicles rose from $513 million in 2020-21 to nearly $1.5 billion in 2021-22. These flows cover a wide range of vehicle types, including cars, buses, three-wheelers (such as e-rickshaws), and two-wheelers. In Indonesia, approximately 67 percent of the $35.6 billion in total investment between 2016 and 2021 went to renewable energy, primarily geothermal and hydropower. Over the same period, investments in new fossil fuel generation have been in decline. In South Africa, debt financing accounts for 75 percent of annual climate finance, with 59 percent of this debt directed toward the clean energy sector. The majority of these flows are facilitated through market-rate debt instruments, with the average cost of capital ranging between 10 and 12 percent.

While IBSA and Indonesia have made serious efforts to make their clean energy markets attractive for investment, there is a growing disconnect between donor rhetoric and the technical delivery of climate finance. To enable a coherent investment strategy and align divergent donor targets, thresholds, and red lines; robust institutional capacity along with political and financial fluency is necessary. In some of the examples discussed in this section, the availability of climate finance falls short due to the lack of hospitable investment environments. In others, despite the availability of funds, there is a lack of institutional capacity to utilize them effectively. To meet targets and accelerate energy transitions, IBSA and Indonesia must strengthen both aspects of their climate finance landscape: climate finance commitments and last-mile delivery. Most importantly, all members of the Global South must elevate local initiatives, establish their own norms, and mold the international financial architecture to meet their needs.

IV. CLEAN TECHNOLOGY COOPERATION AND DIVERSIFYING SUPPLY CHAINS

While international climate finance remains fragmented and structurally unequal, IBSA and Indonesia are advancing simultaneous strategies to secure domestic control over their clean energy transitions. Besides financial gaps, these countries face sensitive technological dependencies, supply chain vulnerabilities, and lack access to emerging technologies. This section outlines how IBSA+Indonesia can strengthen cooperation in clean technology development and supply chain diversification to reduce reliance on external actors and to create resilient, locally anchored clean energy industries. For that to be possible, strategic industrial policies, investment in innovation ecosystems, and coordinated regional standards and efforts are needed.

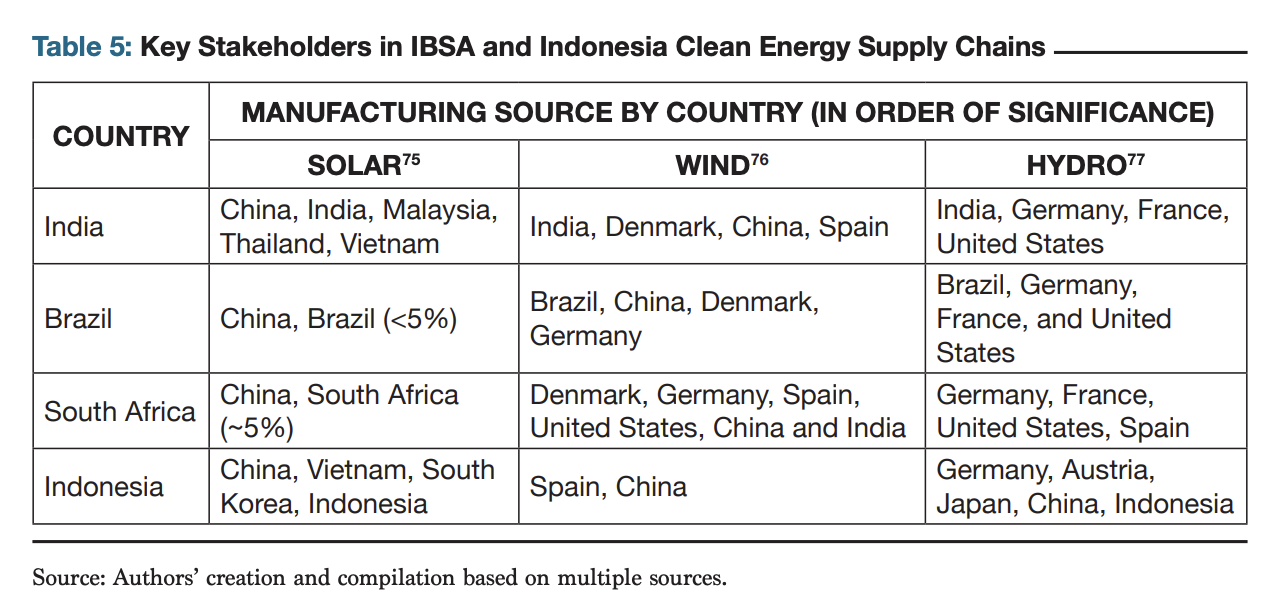

Collaborating on industrial strategy, especially in clean technology, offers a strategic opportunity to reduce external exposure, which is particularly urgent given the current patterns of technological dependence across IBSA and Indonesia. As shown in Table 5, all four countries rely heavily on external manufacturers, especially China and Europe, for key clean energy inputs. Solar manufacturing is particularly concentrated, with China dominating across the board. Wind and hydro technologies have more diverse sourcing patterns, offering potential opportunities for diversification. India and Brazil, for example, already contribute to wind manufacturing and could strengthen value chains with partners like Denmark and Spain. Solar energy faces greater challenges. Recent research indicates that the main obstacle in India and Brazil is not technological capacity but the high cost of capital. Diversifying solar photovoltaic (PV) supply chains outside China could increase manufacturing costs by about 30 percent, mainly due to high capital costs rather than a lack of technical capacity an issue likely mirrored in South Africa and Indonesia. Addressing these structural barriers through joint financing platforms or special investment incentives could boost domestic manufacturing capacity in crucial technologies.

Currently, China has become the leading power in the global clean energy supply chain. It processes over 60 percent of the world's rare earth elements and refines about 90 percent of battery-grade lithium. China also accounts for 70 percent of the global manufacturing value for all major clean energy technologies including solar PV, wind, batteries, electrolyzers, heat pumps, and electric vehicles. In response, Western economies are adopting aggressive, subsidy-heavy industrial policies, such as the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act and the European Union's (EU) Green Deal Industrial Plan, to reduce dependence on Chinese inputs by supporting domestic clean energy production. While these efforts aim to secure supply chains and promote decarbonization, they also deepen existing structural inequalities. Although the economies of the Global South have not significantly contributed to the historical buildup of atmospheric CO2, they are the first to suffer from its harmful effects, which are worsened by their reliance on fossil fuels for energy security, limited access to concessional finance, and technology.

These geopolitical concentrations are further aggravated by the Western subsidy regimes and trade policies, such as the European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The CBAM imposes a carbon tariff on imports of emission-intensive goods into the European Union, including steel, cement, and fertilizers. Although the CBAM is intended to help reduce emissions, it disproportionately impacts countries with high industrial emissions and limited capacity for decarbonization. By applying a uniform carbon price across different development contexts, CBAM risks perpetuating historical inequalities. A report by the Centre for Science and Environment estimated that, at a

rate of €100 (or $106) per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent, CBAM would impose an average annual tax burden of 25 percent on the value of CBAM-covered goods exported to the EU by India. Similarly, Africa faces export losses of up to 14 percent in aluminum and a 0.5 percent decline in GDP. These measures are being implemented without commitments for financing, technology, or transitional support, thus shifting the burden of decarbonization onto developing countries. Without fair frameworks, the Global South could be further marginalized in a subsidy-driven green economy.

Nonetheless, some policymakers argue that these pressures, though unjust, could encourage industrial growth in the Global South by motivating countries to adopt low-carbon standards, boost domestic manufacturing, and become more competitive in emerging cleantech value chains. For example, South Africa has started integrating carbon pricing into its domestic framework and launched the Just Energy Transition Investment Plan (JET-IP), supported by $8.5 billion in pledges from international partners, to promote a low-carbon, socially inclusive transition. However, while these efforts show potential benefits, the broader landscape remains structurally unequal few countries in the Global South have the fiscal space, institutional capacity, or technological access to absorb the short-term costs of CBAM while reaping long-term gains. Without reforms in global trade, finance, and technology governance, these industrial opportunities may remain largely inaccessible. These dynamics highlight the necessity of a coordinated strategy to localize and rebalance clean energy supply chains. As shown in Table 5, current sourcing patterns across IBSA and Indonesia reflect opportunities and risks in the clean tech manufacturing landscape.

To avoid that outcome, IBSA+Indonesia cooperation must go beyond shared structural disadvantages, to build practical, forward-looking industrial alliances. The Global South must adopt strategic industrial policies that identify important value chains and leverage state capacity to build long-term competitive advantages. Countries like Brazil, India, South Africa, and Indonesia should be viewed not just as resource suppliers but as emerging economic blocs with the potential to become self-sufficient clean technology markets, driven by regional demand, innovation ecosystems, and labor-intensive manufacturing. This involves going beyond extraction to develop comprehensive capabilities in sectors such as solar PV, batteries, green hydrogen, and grid infrastructure. Additionally, the Global South must define its value proposition not only in providing raw materials but also in shaping platform-level agendas, setting standards, and asserting leadership in global climate governance.

Increasingly, these countries are no longer content with merely following Western frameworks, such as CBAM. Instead, they aim to establish their own standards in areas like trade rules, logistics, and technology regulation. Initiatives such as India's Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes, the African Union's Green Minerals Strategy, and Brazil's emerging green hydrogen plan show a change in mindset. The main challenge is expanding these efforts through coordinated investment, regional cooperation, and multilateral engagement that prioritize the development goals of the Global South, rather than just adopting frameworks created by others.

Critical Minerals

As clean energy infrastructure expands across the Global South, countries are focusing on securing the upstream materials that enable this growth. Critical minerals, such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements, are no longer viewed simply as commodities to be freely traded on global markets but as strategic assets linked to national development goals. By moving away from a free market approach, governments aim to ensure that mineral wealth leads to industrial growth, job creation, and domestic technological advancement. India's Critical Mineral Mission, Indonesia's export banks, and South Africa's draft mining reforms reflect a growing consensus on the importance of retaining value locally rather than exporting raw materials overseas. Brazil's new BYD electric vehicle plant in Bahia exemplifies this shift toward vertically integrated industrial strategies, from mining to clean tech manufacturing.

However, resource sovereignty alone is not enough. Cases like Mexico's state-led LitioMx illustrate the risks of pursuing resource nationalism without proper institutional readiness, which led to regulatory bottlenecks and investment uncertainty. The strategic goal for these developing countries remains to break historical patterns of extractivism and establish a more sovereign and equitable role in the global energy transition. One that relies not only on access to critical materials and domestic manufacturing but also on developing the necessary infrastructure to support and expand clean technologies.

Grid Modernization and Storage

Grid development and battery storage have become critical bottlenecks for many countries in the Global South. While wind and solar PV capacity are expanding rapidly, infrastructure often lags, resulting in delays in project deployment and reduced system efficiency. Globally, over 3,000 GW of renewable projects, 1,500 GW of which are in advanced stages, are stuck in grid connection queues, equivalent to five times the solar and wind capacity added in 2022. In several fast-growing economies, rising electrification and demand are outpacing grid readiness. Microgrids and battery storage can supplement infrastructure, but they cannot fully replace the need for modernized grids. Smarter, more resilient grids, facilitated by stronger regulatory frameworks, are essential for turning clean energy capacity into a reliable supply.

Several countries are beginning to address these gaps. South Africa has launched the continent's largest battery energy storage system (BESS), which is expected to support the design, procurement, installation, and sustainable operation of nearly 360 megawatts (MW) of large-scale energy storage infrastructure at six Eskom substation sites. India, by comparison, had installed 219.1 MW of BESS as of March 2024. Indonesia is piloting 5-10 MW systems, aiming to implement BESS across its power plants. Brazil, meanwhile, has conducted its first-ever auction to add batteries and storage systems to its grid. The planned batteries will help store energy from wind and solar sources which, although increasingly important in Brazil's energy mix, remain less predictable than traditional thermoelectric or hydropower units, thus aiding in balancing variability and ensuring grid reliability.

Still, without modern grids and large-scale storage, the growth of renewable energy in the Global South risks falling short of its potential. Battery deployment and grid upgrades must be regarded as essential infrastructure for a reliable and resilient clean energy future. However, deploying clean technologies at scale requires more than just physical infrastructure. It also depends on knowledge infrastructure. Without localized expertise, standards, and institutional support, even the most advanced technologies cannot succeed. As emerging technologies like clean hydrogen, small modular nuclear reactors, and long-duration storage evolve, the Global South must choose whether to remain passive recipients of innovation or active co-developers. Doing so will depend not only on investments but on deeper cooperation among research institutions, regulatory bodies, and innovation hubs.

Co-Development of Emerging Clean Technology

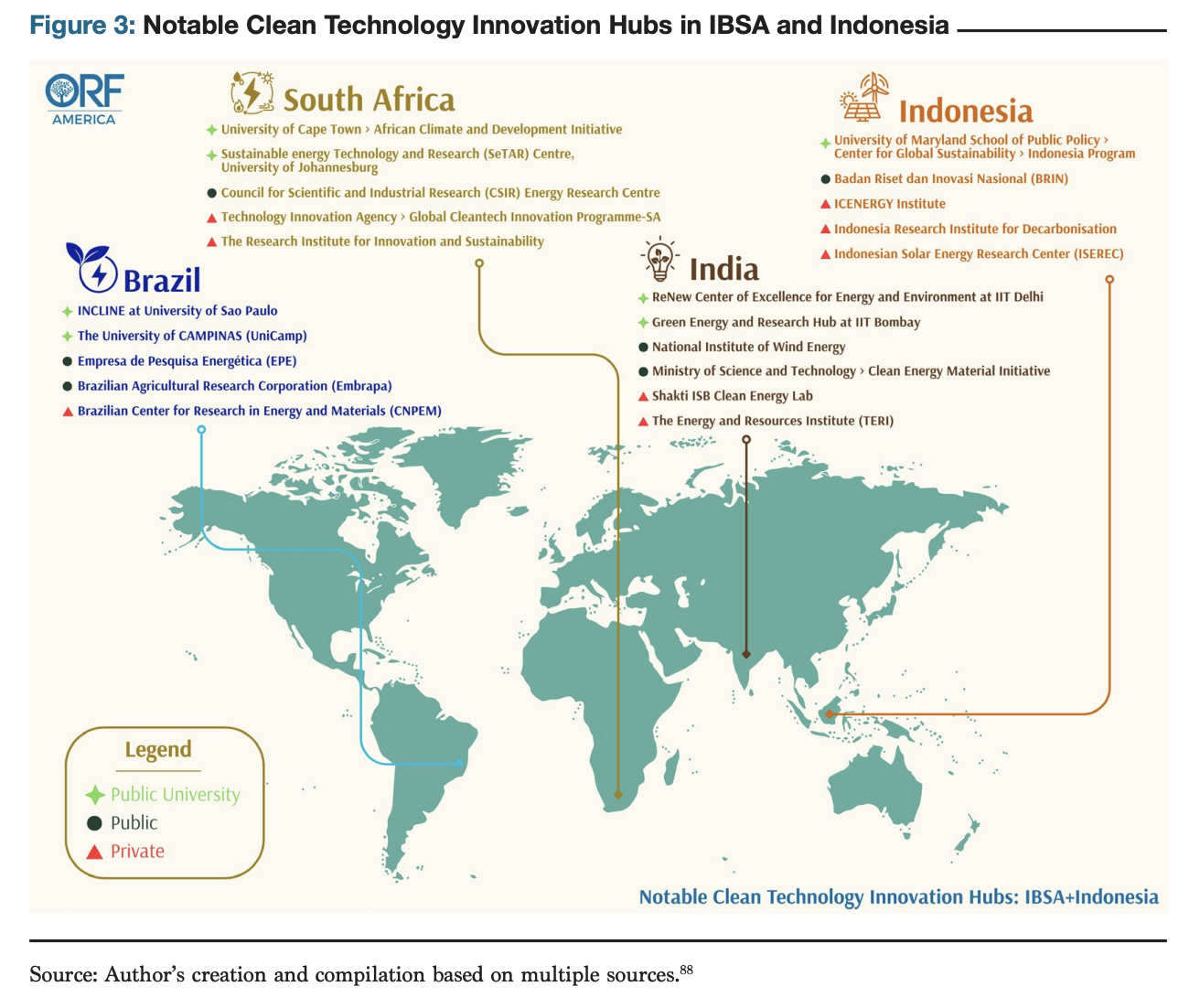

The growing focus on technical capacity and co-development is increasingly reflected in the rise of domestic research and innovation institutions across the Global South. These hubs are not only advancing frontier technologies, such as biofuels and green hydrogen, but are also emerging as key enablers of clean energy deployment through their focus on grid modernization, battery storage, and infrastructure innovation. In India, the Clean Energy Material Initiative (CEMI) advances next-generation energy systems through research on advanced materials, with a strong emphasis on solar technologies and energy storage. Brazil's Center for Research in Energy and Materials plays a vital role in bioenergy, nanotechnology, and sustainable fuels, while also contributing to grid-energy technologies that support the integration of variable renewable energy sources. South Africa's Global Cleantech Innovation Programme (GCIP-SA), led by its Technology Innovation Agency, supports clean tech entrepreneurs and small and medium enterprises, and aims to tackle real-world barriers to clean energy access, including energy reliability and storage. Indonesia's Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional (BRIN) is not only developing bio-based technologies such as sustainable aviation fuels from coconut oil but also exploring modular and distributed storage systems that are better suited to the country's archipelagic geography (see Figure 3).

Crucially, these institutions offer more than just technological progress; they represent an evolving knowledge infrastructure essential for absorbing, adapting, and scaling clean energy solutions. By investing in their domestic research ecosystems, IBSA and Indonesia are laying the foundation for greater self-reliance in clean energy value chains, reducing dependence on external technologies and standards. They also serve as regional hubs for South-South cooperation, providing platforms for the joint development of technologies, standard-setting coordination, and shared innovation in areas such as grid digitalization, long-duration energy storage, and distributed energy systems. These efforts collectively reflect a strategic shift, where countries in the Global South are no longer merely adopting imported solutions. They are striving to shape the clean energy transition through indigenous innovation and institution-building. This momentum must be complemented by broader cooperation across IBSA+Indonesia to expand these models and ensure a more equitable, secure, and resilient energy future.

V. CONCLUSION

As some of the largest developing economies in the Global South, India, Brazil, South Africa, and Indonesia have embarked on an ambitious path to increase their share of clean energy and achieve their NDC commitments over the coming decades. To do so, they must address similar challenges, including phasing out legacy fossil fuel infrastructure, overcoming the high cost of capital, adapting to concentrated clean energy supply chains and limited access to clean technologies. The success of these countries is key, as they represent some of the fastest-growing clean energy markets in the world. Their collective actions will significantly shape global climate outcomes.

IBSA+Indonesia as a group offers significant opportunities for coordination and collaboration to achieve a just and equitable energy transition. As a formalized grouping focused on energy transitions, IBSA and Indonesia should align their efforts by exploring five key policy priorities: workforce transitions strategies to phase out fossil fuels, building capacity to absorb climate finance, alignment to facilitate collective bargaining of the price of capital, clean industrial strategies and fostering innovation to ensure long-term competitiveness.

To bridge the disconnect between ambition and technical delivery of climate finance IBSA and Indonesia must bolster the institutional capacity and cross-ministerial alignment of their climate vehicles, including central banks, climate banks, and ministries. This can be achieved through the implementation of joint programs that strengthen the financial and political literacy of government employees critical to the energy transition and ensure last-mile delivery of climate finance. Furthermore, these countries have a significant opportunity to set norms around climate investments in the Global South by harmonizing climate finance taxonomies and jointly elevating similar local initiatives for greater eater investor visibility. This type of alignment will also facilitate the collective bargaining power of this grouping to negotiate the price of capital and build a long-term pipeline for investments in their respective energy transitions.

IBSA and Indonesia have deployed several incentives and domestic climate finance instruments to crowd in private investment. Shared learning from experiences in different clean energy sectors has great value if similar contexts can be identified at both the central and local levels. As these countries develop long-term clean industrial strategies, they must establish a recurring knowledge-sharing and feedback process that advances these strategies and collectively addresses market uncertainties, such as pandemics and conflict. This can ensure the long-term competitive advantage of IBSA + Indonesia countries.

The innovation of clean technology and emerging fuels is crucial to maintaining the long-term competitive advantage of IBSA and Indonesia's energy transitions. In this report, we have identified a few notable clean tech research hubs, however, with booming entrepreneurship and innovation in these sectors, there will undoubtedly be many more names to add to these lists. IBSA and Indonesia should expand this list, maintain a current database, and establish a cooperative framework to co-develop clean technologies of the future.

A strategy must be in place to replace jobs lost in the energy transition, particularly given the sensitivities surrounding fossil fuel sectors in IBSA and Indonesia. These countries must aim to directly mitigate adverse outcomes by offering a combination of vocational training and unemployment benefits. They can benefit by identifying transferable skills and effective place-based policies that address a variety of socio-cultural contexts. Collectively addressing these challenges of energy transitions can lighten the burden on fossil fuels to meet projected energy demand.

Beyond national collaboration, these four countries must continue to uphold unified leadership in global climate governance and trade discussions. Engaging in multilateral platforms such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the World Trade Organization, and G20, is essential to shape international norms that reflect these nations’ development goals while safeguarding their economic interests. By aligning diplomatic efforts and harmonizing policy frameworks, India, Brazil, South Africa, and Indonesia can assert a just and equitable energy transition.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jeffrey D. Bean, Dhruva Jaishankar, and Anit Mukherjee for their review, comments, and suggestions on earlier drafts of this report. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the valuable contributions of participants in the workshop, “Mapping Clean Energy Commitments and Ambitions in IBSA + Indonesia,” held on June 11, 2025, at ORF America. The insights and perspectives shared during this multi-stakeholder dialogue, featuring experts and practitioners from across the IBSA countries and Indonesia, significantly enriched the research and recommendations presented in this report. This publication is a part of ORF America’s Energy and Climate Program. The views and analyses expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of ORF America, its affiliates, or partner institutions.

Cover image courtesy iStockPhoto: Antonio Correa d Almeida

Note: Citations and references can be found in the PDF version of this paper available here.