Background Paper No. 13

BY Udaibir Das, Anit Mukherjee, and Medha Prasanna

Summary:

Financing development is at a crossroads. Having navigated reconstruction, development, and crisis recovery demands over the last eight decades, the institutional architecture at the global level is confronting the twin pressures of supporting the unfinished development agenda while taking on the responsibility of new global priorities. Mobilizing additional financing remains a considerable challenge for implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. There is an immediacy to scale up investments in climate action and biodiversity finance. Simultaneously, controversies exist about the allocative efficiency of development financing as practiced today. On the positive side, there is cautious hope for fundamental reform, driven by the realization that failure to respond promptly and effectively will make global development goals less attainable and global challenges more acute. The G20, under India’s presidency, and a wide array of stakeholders have signaled their intention to improve the international system to finance development. This background paper focuses on the foremost purveyors of development finance - the Multilateral, Regional, and Sub Regional Development Banks - as well as new and emerging sources. It proposes four essentials for the design of future reforms: prioritizing the financing of global public goods such as climate change and biodiversity, agriculture, and health and infectious disease; adopting regional approaches to development challenges; highlighting the views of borrowers; and building data systems and capacity to accelerate development.

1. The Context: Shifting Sands of Development Finance

Development finance is a diverse and complex construct with no standard definition. In broad terms, it implies finance that supports medium- to long-term activities for investment purposes. Traditionally, financing of development has been a cooperative undertaking across four pillars: (i) effective deployment of multilateral development bank (MDB) resources; (ii) strengthening domestic resource mobilization; (iii) allocation of official development assistance (ODA); and (iv) keeping trade and capital flow regimes free and supportive of private investment in critical sectors such as infrastructure.

The global pandemic and the interconnected crises of climate change, food, energy, cost of living, and debt have struck a blow to the decades-old consensus on development. Almost one-third of the world’s least developed countries are in macroeconomic distress or face a high risk of falling into one. They are grappling with the recurring costs of climate-related devastation. High rates of unemployment are preventing countries from reaping the benefits of the “techno-graphic dividend” and exclusion from mainstream financial services are holding back the transition to economic platforms that could help address the pressing needs of the low-income countries, small states, and countries that are fragile and in conflict.

The upshot of a protracted crisis and uncertainty from the mid-2000s is that middle-income countries and several emerging economies need to realign their development framework and prepare for a rapidly altering landscape in a resilient and sustainable manner. For this to happen, the amount and modes of access to development finance must become more participatory and inclusive.

Several “roadmaps” have been proposed to increase the resources to bridge this gap. These include the Bridgetown Agenda 2022, focused on the MDBs; the United Nations Roadmap for Financing the 2030 Agenda to align the international financing system behind the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); and the High-level Expert Group and Independent Panel on climate finance and pandemic preparedness that estimate the costs of meeting current and future threats to global development.

Meanwhile, the global economic landscape and the sources of development assistance are being profoundly transformed. The locus of global growth is shifting rapidly to a more extensive set of countries in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Consequently, countries like Brazil, China, India, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are becoming the “new international donors” within their spheres of influence and beyond.

The traditional architecture of development finance, therefore, has to keep in step with the shifts in the balance of global economic power and social aspirations – one of the several reasons for the calls to reform the most important institutions, namely the MDBs. With private sources of financing development outstripping resources available from the MDBs, integration of the private sector as well as defining its role and accountability must become a core part of any remodeling of the international development finance architecture.

2. The Architecture of Global Development Finance: A Complex Landscape

The international architecture for financing development has evolved from focusing on post-World War II reconstruction to poverty reduction in the 1970s to concentrating on inclusive and sustainable long-term economic growth today. The primary motivation was to aid those countries that needed financial support in sectors where domestic resources required a boost and governments could not implement complex programs in various sectors. A behemoth structure has grown organically as global, regional, or sub-regional development challenges have evolved to achieve this collective pursuit of the goal.

The current global development finance architecture broadly comprises a six-tiered official sector setup (See Annex 1 for more details on the governance structure of select MDBs). Underpinning this classification lies an intricate system determining which agency extends what type of financing, and the associated tradeoffs between the financing volume, its nature (grant/concessional and non-concessional), and duration (short-term bridge finance or long-term and extendable financing). For example, a country can contribute an amount in an MDB for grant (concessional) funding or could add the same amount as capital in an MDB or a regional development bank resulting in mobilizing “non-concessional” funding in the form of loans to recipient countries at a lower cost vis-à-vis borrowing at market rates. Concessional financing can also be utilized for the new global priorities by making the effective interest rates on loans affordable for a country to borrow for climate adaptation and some aspects of climate mitigation.

We explain the six tiers of development finance below:

(i) The World Bank Group. This comprises five agencies: the International Development Association (IDA), IBRD, International Finance Corporation (IFC), Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), and the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). While the five institutions comprise the World Bank Group, each has its country membership, governing boards, and articles of agreement. Together, IBRD and IDA form what is commonly known as the World Bank. The two partners with relevant governments provide financing, policy advice, and technical assistance. IDA focuses on the world’s poorest countries, while IBRD assists middle-income and creditworthy poorer countries.

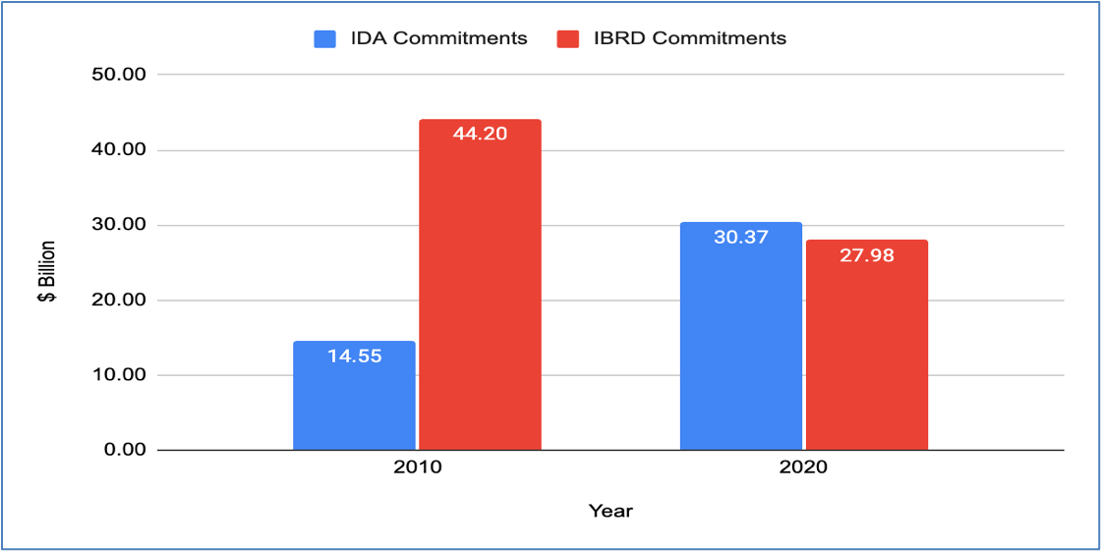

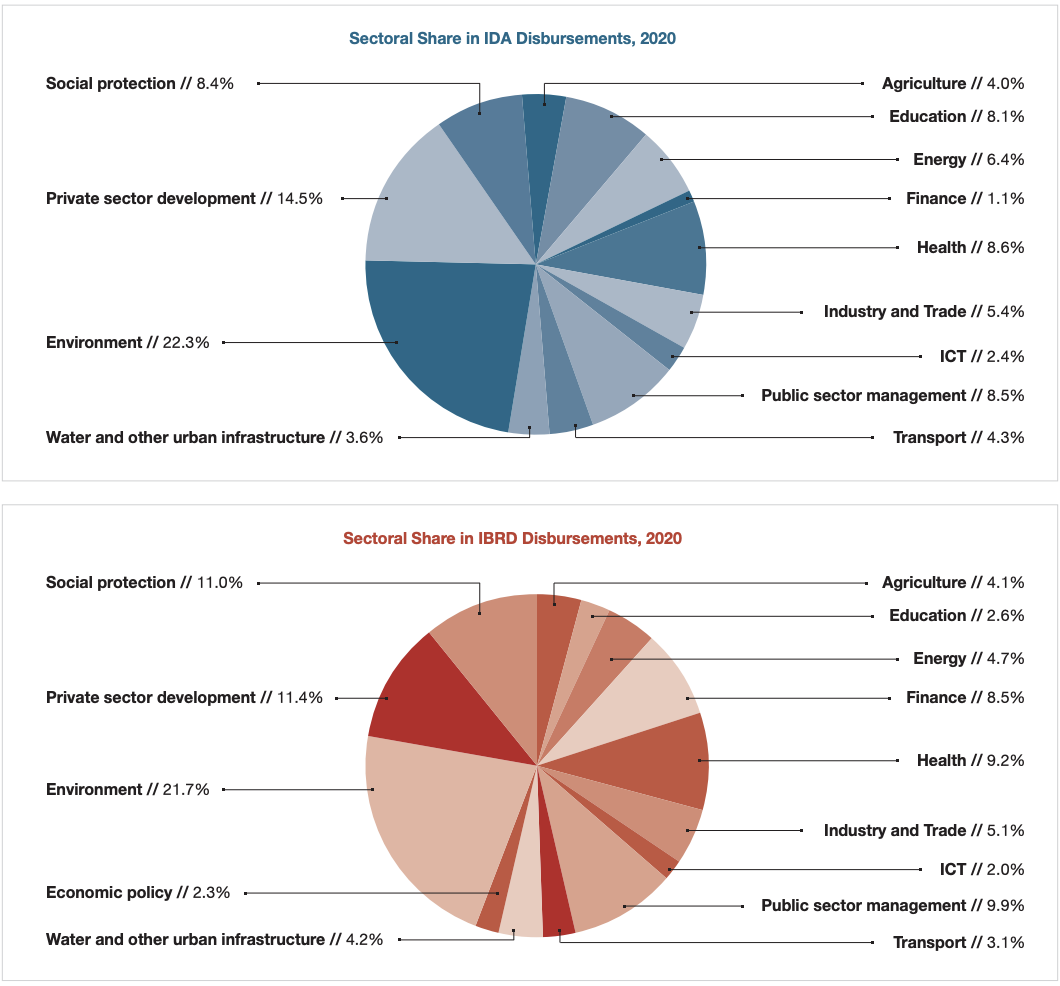

Figure 1 shows IDA and IBRD commitments in 2010 and 2020. This shows nearly a doubling of IDA commitments and a decrease by nearly a third for IBRD after a decade. IDA and IBRD activities help countries set the groundwork to enable private investment. Figure 2 indicates that the largest sectors for IDA disbursements are the environment, public and private sector development, social protection, health, and education in that order. These sectoral shares are broadly similar for IBRD and have remained largely stable over the decade. The IFC, MIGA, and ICSID focus on strengthening the private sector participation in developing countries via financing, technical assistance, political risk insurance, and settlement of disputes to private enterprises, including financial institutions. They may play an essential role as the World Bank seeks to encourage the private sector to be more active, especially in building resilience to mitigating climate change.

Figure 1: IDA and IBRD Commitments, 2010 and 2020

Source: World Bank Annual Reports, 2010 and 2020.

Figure 2: Sectoral Share in IDA and IBRD Disbursements, 2020

Source: World Bank Annual Report 2020.

(ii) Regional Development Banks (RDBs). The number of development banks has increased rapidly since the 1950s, encouraged by the World Bank, as well as geopolitical imperatives such as the European integration after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and China’s rise as an economic power. This was principally to “localize” development assistance through institutions with the presence, knowledge, and capacity to address regional challenges. The sizeable RDBs include the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), established in 1959; the Asian Development Bank (ADB), which began operations in 1966; and the African Development Bank (AfDB), established in 1964. Others that followed are the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), the European Investment Bank (EIB), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and more recently, the New Development Bank (NDB) with the BRICS countries as the significant NDB shareholders.

(iii) Sub-regional development banks and financial institutions (SRDBs). The SRDBs intersect with The World Bank Group, RDBs, and national development banks (see below). While several entities straddle across both systems, the SRDBs have specific characteristics and more targeted (and limited) functions, such as the infrastructure sector. Questions are often raised about the relevance of SRDBs in bridging the infrastructure financing gap and overlaps with the RDBs. The experience with SRDBs shows vast regional differences regarding the impact of bridging financing gaps at a local level. Considerable scope exists to enhance these SRDBs and leverage the opportunities facing them. Some of the SRDBs include the Corporacion Andina de Fomento development bank of Latin America, the Caribbean Development Bank, the Central American Bank for Economic Integration, the European Commission, the European Investment Bank, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the Nordic Development Fund, the Nordic Investment Bank, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) Fund for International Development, the West African Development Bank, and the East African Development Bank.

(iv) National public development banks: National Development Banks (NDBs) are entities set up by countries to directly fund or incentivize private sector investment in households and small and medium enterprises. In doing so, they seek to promote strategic sectors of the economy, such as agriculture, international trade, housing, tourism, infrastructure, and green industries, among other sectors. The policy approach towards the NDBs has changed from full support for their establishment during the 1960s and 1970s to a more cautious approach during the 1980s and 1990s, which saw more closure or privatization of state-owned financial institutions.

(v) Direct bilateral ODA: Bilateral development aid directly flows from official (government) sources to the recipient country. Grants, loans, and credits for defense purposes or commercial objectives are excluded, and transfer payments to the private sector are not counted.

(vi) Vertical global aid channels: Vertical funds focused on specific development objectives, such as the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF), have become a funding vehicle of choice since the early 1990s. These are global programs for allocating ODA focusing on an issue or theme intended to cut across more than one region. Some have raised doubts about the polarization between vertical financing (aiming for specific outcomes) and horizontal financing (aimed to improve the overall development ecosystem and capacity). Some have proposed “diagonal” funding as a better model for specific results via improved local capacity, systems, and budget.

Non-traditional Actors: Newer players who may not fit the above classification have also started actively participating in development finance. In recent years, private giving by foundations, non-governmental organizations, religious organizations, and private voluntary organizations has equaled official aid flows. Non-traditional bilateral donors have also grown to include emerging markets such as Brazil, India, China, Turkey, and Thailand. Moreover, organizations such as the Global Fund for AIDS, TB, and Malaria (GFATM), Stop TB, and Malaria No More raise and deploy significant resources from a mix of traditional and new donors and private corporations’ philanthropies to tackle the global burden of communicable diseases.

As a result, a complex, intertwined, and unwieldy set of institutions, players, financing products, and schemes has emerged. While each is playing its part, coherence has become diluted. Financial resources and skills needed to address current and future economic development needs have been fragmented. As calls to reform the existing MDB system gained prominence, especially after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the G20 at their Pittsburgh summit in 2009 called for greater coordination and cooperation in the MDBs, emphasizing comparative advantage and minimizing overlap with other global and private financial institutions. Those voices have gained further momentum as the world faces a backsliding on development achievements in the aftermath of the worldwide pandemic and the emerging risk of climate change.

3. Strategic Reform and a Four-Point Agenda

As the largest source of development finance, the MDBs will have a significant role in supporting low- and middle-income countries as they seek to respond more assertively in dealing with the development imperatives of today and tomorrow. Several MDBs and development financiers have begun to articulate their vision and strategies, such as the Development Committee.

The four policy priorities that should be integrated in their operating model as the MDBs chart their future agenda are:

I. Financing Development-related Global Public Goods

With greater global integration, developing countries face increasing risks over which they have minimal control and which no one nation, rich or poor, has the incentive to tackle alone. Often these conflict with political or grassroots priorities leading to a demand for financing and capacity creation. MDBs are uniquely positioned to take leadership in financing global public goods that are most relevant to development priorities at the worldwide level. The four development-related global public goods (DR-GPGs) that meet the criteria are climate change and biodiversity, agriculture, health and infectious disease, and data for development on a sustainable and informed basis. While climate change mitigation and adaptation have been at the forefront of the global debate on MDB reform, COVID-19 has highlighted the role of MDBs as a coordinating body to finance preparations for future pandemics. Agriculture falls at the intersection of climate and development. This sector is most affected by frequent adverse weather events, long-term changes in weather patterns, and a general decline in the quality of ecosystem services that is a consequence of the climate crisis. One key lesson of the global pandemic is that creating digital public infrastructure is a global public good and should also be a focus area for the future deployment of MDB resources.

II. Pivoting from country-only focus to regional approaches

The MDBs have operated on a model where country governments are treated as “clients.” This implies that the operations of the World Bank are determined by the country’s demand for financing and expertise. Assuming the MDBs reorient their strategic priorities to focus more on DR-GPGs, that would entail moving away from an exclusively country-focused operational model to one where regional importance becomes increasingly important from the perspective of project financing (water and forests, for example). In the global pandemic, the RDBs have also played a critical role. Together from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 through June 2022 RDBs have disbursed around $50 billion to help developing countries through the emergency. After the global pandemic, they have also taken a regional approach to resume cross-border trade, migration, and protocols for Covid vaccine certificates. A closer partnership between the MDBs and the RDBs could help better explain the local on-the-ground aspects of development findings and better customize the financing terms.

III. Moving to a borrower-centric approach

The lack of representation of the “user’s viewpoint” is a material shortcoming of the current architecture. It explains why many borrowers have sought recourse from nontraditional sources of bilateral financing and market-based funding with a premium over the rates offered by MDBs. Therefore, two issues must be at the heart of the MDB reform agenda: (I) demonstrable inclusiveness and (ii) solutions responsive to those needing global resources. To fulfill the twin goals of inclusiveness and responsiveness, the voices of borrowers must be clearly articulated, heard, and honored before developing reformed lending products and services. It requires proportional products and services that borrowing governments can own. Several borrower-led financing arms have emerged in Latin America, Africa, and Eastern Europe/Central Asia but none in a meaningful manner. A more systematized and analytically robust mechanism to determine user shifts should be made a priority for all the upcoming global engagements on development finance. The benefits of such an approach will help borrowing countries to communicate better with their local stakeholders. This will also allow borrowers to understand the need to leverage the efficiency of their resources when partnering with the MDBs. It will help inform the right policy choices and the needed legal, institutional, and political reforms. Borrower-led reform of the MDBs thus has the potential to play a more significant role in tackling global development challenges.

The most difficult challenge in restructuring MDBs to face the new priorities is the balance between (traditional) borrower priorities and the push, largely from non-borrowing countries, towards addressing global public goods (GPGs). The tension plays out at two levels especially for low-income countries: (i) country priorities with a “poverty focus” versus GPGs, and (ii) country priorities versus regional priorities, including those of a public good nature, such as public health. Borrowing countries are more than clients of MDBs. As shareholders, they would like to address their own priorities in lending operations. By the nature of GPGs, there is little incentive to prioritize them from their viewpoint, especially if the emissions crisis is seen as having been caused by the non-borrowing, developed countries. However, among the shareholders, large middle-income countries are in between with a mix of development and GPG concerns. In the current scenario, countries such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, and Mexico are particularly well-situated to help navigate the evolution in the role and nature of MDB finance going forward.

IV. Capacity building and improving publicly accessible data platforms

An essential precondition for any modified development financing architecture is to ensure capacity on the ground to use and manage investment flows. Developing countries face critical monetary policy, exchange rate, and debt challenges. With the current push for funding, resources, and broader private sector participation, the borrowing developing country’s government will confront tricky policy choices on structural priorities, reform sequencing, and, most importantly, its capacity to manage complex balance sheet risks and macroeconomic trade-offs. In a broader macroeconomic context, capacity strengthening will help improve the quality of outcomes expected from using global resources. Along with capacity constraints, significant data gaps hinder needs assessment and the ability to prioritize scarce development finance resources. One specific aspect of attracting and retaining investment flows is access to reliable data and information. Data systems take time to set up and release for public use. Addressing data and informational shortcomings and establishing new platforms using technology, big data, and machine learning must become an immediate priority. Of course, good data cannot replace sound fundamentals, and investors are keen to comprehend better the investment regime, risk attributes, and consistency in evaluating outcomes.

4. Conclusion

Sustainable growth and inclusive societies come from how the economy works and institutions respond. The scale and complexities of what the globe faces outpace our collective ability to deal with them. While all stakeholders may claim that everyone is together this time, correcting the path set decades ago must be historic. This time it must be different, and the responsibility of development must not become, one more time, the burden for future generations to carry. The experience of the last seventy years demonstrates that socioeconomic problems fixed via policy repression and short-term measures only feed discontent and resentment, opening the way for extreme social behavior. Through financing development-related global public goods, shifting to regional priorities and a borrower-centric approach, and enhancing countries’ management capacity, mainly via data, the full spectrum of multilateral development institutions can bend the trajectory of our shared global future. Often, there is understandable tension between development priorities at the global and national levels. Several borrowing countries rightly assert their rights and privileges as shareholders of MDBs and RDBs and resist being viewed just as clients needing money. They demand better integration of their local priorities in the strategic agenda of the global agencies. A few regional lending windows offer incentives for countries to work together on joint priorities, but it is often difficult to coordinate since most operations remain country based.

The developing world deserves to collectively become the pillar of stability, especially from the point of view of raising and deploying significantly larger resources to address global challenges. Some of the reforms proposed here are less radical than they may appear – the objective is to find areas of both continuity and change. As has been remarked, change is needed, "Because things are the way they are, things will not stay the way they are."

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Alan Gelb, Pinaki Chakraborty, and Scott Morris for their review, comments, and suggestions on an earlier draft of this paper.

The paper is part of ORF America’s G20 initiative supported by the Child Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF). This background paper reflects the personal research, analysis, and views of the authors, and does not represent the position of either of these institutions, their affiliates, or partners.

Note: The footnotes can be found in the PDF file.