Special report no. 9

BY MEDHA PRASANNA, caroline arkalji, and PIYUSH VERMA

I. Introduction

Over the past decade, just and equitable energy transitions have emerged as a defining priority for the Global South's development agenda. However, persistent gaps in finance, technology, and resilient supply chains continue to slow progress. As the global energy transition reaches a critical inflection point, the Global South is no longer only adapting but now actively shaping pathways centered on sustainability, equity, and justice. In the context of consecutive G20 presidencies held by Indonesia, India, Brazil, and South Africa, as well as Brazil's COP30 presidency, the IBSA+Indonesia partnership holds significant potential to leverage political momentum, reflect diverse development challenges, and catalyze deeper South-South cooperation.

The synergies among these four economies are considerable, with combined gross domestic product (GDP) exceeding $8 trillion and a population representing nearly 25 percent of the world's output, offering both scale and diversity to drive meaningful change. At the same time, as electrification and development accelerate, electricity demand across the four countries is projected to rise by 38 to 55 percent by 2035, presenting a significant decarbonization challenge.

Each country in the group has used its G20 presidency to advance national and collective priorities on the energy transition. As COP30 host, Brazil has further elevated this agenda through its focus on socio-bioeconomic issues, highlighting new development-aligned pathways for transition. With global attention now shifting toward implementation and delivery, IBSA+Indonesia has an opportunity to consolidate this momentum and emerge as a sustained set of leaders in shaping global energy transitions.

Building on this shared trajectory, recent IBSA+Indonesia dialogues hosted by ORF America have helped clarify common priorities for green transitions, including climate finance, resilient supply chains, and technology cooperation. As the conversation among the quartet of partners has evolved, the focus has moved beyond diagnosing challenges toward identifying solutions and pathways for collective action. Earlier analysis captured the shared challenges and emerging momentum across the four countries. This effort advances that work by outlining actionable pathways to translate dialogue into a more structured, durable platform for cooperation.

The report is organized to move from context to solutions. The opening section reflects on the achievements of IBSA+Indonesia energy transitions, highlighting concrete steps already taken to champion Global South priorities on the international stage. The second section examines unresolved challenges and persistent barriers to advancing both energy transition and development objectives, including investment shortfalls, technology gaps, fragmented supply chains, and exposure to global market volatility. The final section presents a forward-looking roadmap for co-creation, outlining pathways to institutionalize IBSA+Indonesia as a platform for collective leadership through six intervention areas: diplomatic harmonization, climate finance mobilization, standards in supply chain diversification and industrial cooperation, joint technological innovation and knowledge exchange, human capital, and energy data governance.

II. COLLECTIVE PROGRESS

Across IBSA+Indonesia, emissions reduction and energy transition pathways are moving at different speeds and taking various shapes, but the story that emerges is less about divergence and more about complementarity. Each country is navigating a familiar set of challenges: rising energy demand, climate vulnerability, the need for reliable power, and the political priority of delivering development while decarbonizing. What makes this moment significant is that each country is also building solutions that others can learn from, adapt, and scale. IBSA+Indonesia's shared challenges, paired with their district strengths, form the foundation for a meaningful cooperation.

Brazil's trajectory illustrates how structural vulnerabilities can catalyze innovation. Although the country relied heavily on hydropower for decades, recurring droughts and extreme weather have exposed the limits of an energy system dependent on rainfall, forcing Brazil to rethink its approach to energy resilience. Its steady shift toward solar and wind has therefore become more than a diversification effort — it is a long-term strategy to guard against growing climate instability. At the same time, Brazil has placed climate ambition at the center of its development agenda through innovative finance and conservation initiatives.

The Amazon Fund, launched in 2008, remains one of the world's leading mechanisms for forest protection, disbursing over $552 million into non-reimbursable investments to cover 139 projects. At COP30, held in Belém (the main entry point to the Amazon) Brazil expanded its climate leadership by launching the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), a mechanism designed to reshape how climate finance values forests and supports tropical conservation. The summit concluded with more than $6.7 billion in announced contributions and the endorsement of the TFF Launch Declaration by 66 countries.

Brazil's leadership extends beyond land use. As a founding member of the Global Biofuels Alliance, it is elevating decades of experience in low-carbon transport fuels to an international platform, an approach that links climate ambition to industrial capability and real-world deployment. This outward-facing strategy is reinforced by Brazil's development finance tools including the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) which connects trade and climate through credit lines for international investors in renewables and by supporting the export of Brazilian goods tied to the green economy. In short, Brazil's progress is not only domestic but it is also increasingly institutional, financial, and diplomatic.

India's progress, meanwhile, demonstrates what scale looks like when ambition meets execution. As of June 2025, India has installed over 250 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy capacity and is already halfway to its 500 GW target by 2030, with solar power driving the majority of additions. What stands out is the dual nature of India's approach: both top-down and bottom-up. National targets and large-scale programs are complemented by policy support for decentralized solutions, especially rooftop solar, where energy access and community livelihoods can reinforce one another. The flagship of this effort is PM Surya Ghar, launched in February 2024, which aims to provide free electricity to 10 million households by 2026-2027. At the same time, India is working to deepen the supply-side foundations of transition. Through policy support such as the Production Linked Scheme (PLI), it is boosting domestic production capacity not only in renewable energy but also across complementary sectors.

India has also translated domestic progress into international leadership through the treaty-based International Solar Alliance (ISA), which now includes 120 member countries. The ISA positions solar adoption as a shared development agenda that addresses practical barriers, including energy access, climate finance, training, and partnerships. In January 2025, the Global Energy Alliance for People and Planet (GEAPP) and ISA partnered to mobilize $100 million for high-impact solar projects, reinforcing India's role as an institutional anchor for the energy transitions of other developing nations. This same logic — development first, with climate integrated — shaped India's diplomatic agenda through the Green Development Pact adopted during its 2023 G20 presidency, elevating the Global South's framing of how economic growth and environmental protection can be advanced together by embedding climate action within development plans.

Indonesia's trajectory highlights a different lever of progress, mobilizing international finance and turning it into coordinated action. Indonesia's Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) has secured substantial commitments totaling over $20 billion from the Global North and development banks. But the significance of the JETP is not only the headline amount, but it is also the governance and coordination that followed. Indonesia's centralized coordination and implementation plans have begun to outline concrete steps toward energy transition goals, while mobilizing an all-of-government approach.

Indonesia also brings sector-specific leadership that complements the biofuels and solar narratives of Brazil and India. As the world's second-largest producer of geothermal energy, it offers lessons on direct use applications, strategic government policy, and the challenge of mobilizing capital for capital-intensive clean energy. The Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) Country Platform managed by PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur, under the Ministry of Finance, combines strong governance and risk systems with project development expertise and the ability to leverage private capital. In doing so, it offers a climate-finance model that other developing and emerging economies can adapt to scale climate action through financially resilient and institutionally anchored mechanisms.

South Africa's progress, shaped by the urgency of moving from a coal-heavy system, illustrates how structured procurement and planning can unlock investment and accelerate diversification. The Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Plan (REIPPP) has been central to attracting over $20 billion in investments, offering a practical roadmap for transparent public-private partnerships. South Africa's JETP, totaling $12.8 billion, has also evolved beyond power into other emissions-intensive sectors like transportation. Through the JETP Funding Platform, South Africa has been transitioning from high-level dialogue to inclusive stakeholder engagement, comprehensive plans, and specific implementation measures.

These efforts are guided by a long-term plan: the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP), which outlines concrete goals toward 2030, incorporates a Carbon Tax Policy, and maps the integration of renewables into the grid. As renewables scale, system flexibility becomes essential, and South Africa is already positioning storage as a significant pillar. Its energy storage market is projected to grow to ZAR14.5 billion ($845 million) by 2035, propelled by rising renewable demand and initiatives such as BESIPPPP (Battery Energy Storage Independent Power Producers Procurement Programme) and Eskom's Battery Energy and Storage System (BESS). The BESIPPPP, led by the South African Department of Mineral Resources and Energy, is a strategic program that procures large-scale battery energy storage from private companies (Independent Power Producers) through a competitive bidding process, showing how competitive procurement can bring private-sector capacity into a national transition strategy.

Taken together, the four countries are not operating in isolation. They are foundational pillars of international frameworks that advance South-South cooperation — including BRICS, IBSA, and the G20 and are actively shaping global energy transition discourse at the UNFCCC, with a strong emphasis on development and social dimensions. Indonesia and South Africa have combined domestic policy reform with international diplomacy to secure Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs), mobilizing large-scale financial commitments to support their energy transitions over the medium term. Brazil and India, in turn, have leveraged leadership in specific renewable sectors — biofuels and solar, respectively — to establish international institutional anchors that promote energy transitions across other developing countries.

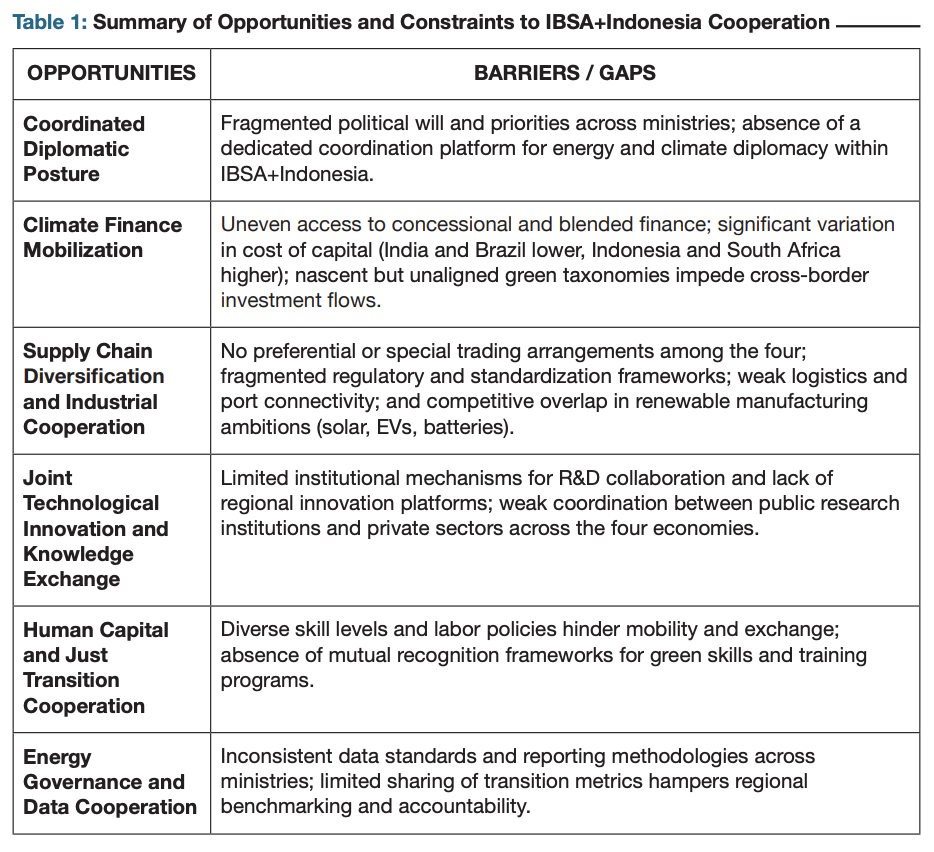

This represents substantial progress, but it remains fragmented. The foundations for deeper cooperation are evident in shared challenges, complementary strengths, and a growing ecosystem of institutions and financial mechanisms across the four countries. What remains missing is a coordinated and sustained platform that can translate parallel leadership into deliberate collaboration on energy transitions in key areas as mapped in Table 1.

Source: International Energy Agency, “Sources of global electricity generation for data centres, Base Case, 2020-2035,” International Energy Agency, April 2025. License: CC BY 4.0.

III. KEY OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS

Coordinated Diplomatic Posture

A crucial gap for IBSA+Indonesia is not ambition, but alignment. Even as the world increasingly looks to these four countries as regional and global leaders, their initiatives often emerge in parallel rather than as parts of a shared strategy shaped by differing political contexts, institutional histories, and policy toolkits. The result is fragmentation, with countries advancing overlapping agendas and sending inconsistent signals. This raises the risk of uncoordinated national policies and ultimately dilutes collective leverage in international forums.

Fragmentation is further reinforced by segmented policy conversations. Debates on risk and finance frequently proceed in isolation from discussions on planning and implementation, while climate diplomacy is too often treated as a niche track rather than a core pillar of economic and geopolitical strategy. Multilateral relationships can also become strained when ideological disagreements in other domains spill into climate and energy cooperation. Deeper integration is therefore needed with the goal of embedding energy transition priorities within broader dialogues on trade, industrial policy, investment rules, and security. Without aligned incentives, export frameworks, and investment guardrails, it remains difficult to build a coherent and complementary diplomatic posture that shapes global standards rather than merely reacting to them.

Climate Finance Mobilization

The mobilization of climate finance is hindered by systemic barriers, most notably the high cost of capital in emerging economies. Clean energy projects can be substantially more expensive in these countries than in developed markets, not necessarily because project fundamentals are weaker, but because financing is priced through inflated country risk premiums, which are often perceived as arbitrary and socially constructed rather than reflective of project level risk. The practical implications are clear. Higher-risk pricing raises hurdle rates, narrows what is bankable, and slows project pipelines even when technology and demand are ready.

These constraints are also uneven across IBSA+Indonesia. Capital costs vary sharply within grouping. The cost of capital in South Africa and Indonesia is estimated to be roughly three times higher than in Brazil and India. This results in divergent transition speeds even when ambition is similar. It also disproportionately penalizes capital-intensive energy priorities such as transmission, storage, grid modernization, and early-stage industrial decarbonization which depend on long-term finance to be viable. Access to finance is further impeded by limited domestic financial capacity and constrained fiscal space across most emerging economies, reducing governments' ability to de-risk projects or provide the concessional layers needed to crowd in private capital.

Finally, green finance standards remain fragmented and insufficiently aligned. Existing taxonomies often reflect largely "Eurocentric" models, creating misaligned standards and capital penalties that complicate cross-border investment flows. These challenges are further exacerbated by policy and regulatory uncertainty, as well as weak implementation and enforcement of critical safeguards, such as credible off-taker guarantees in power purchase agreements (PPAs), which heighten perceived risk and discourage investment at scale.

Supply Chain Diversification and Industrial Cooperation

Supply chain issues are compounded by continued reliance on the developed North for technology, capital equipment, and, in many cases, access to critical minerals. Too often, this relationship is framed through an extractivist lens focused on securing minerals for consumer-country industries rather than building shared and resilient value chains. A critical gap is the lack of domestic and regional manufacturing capacity across much of the Global South. When manufacturing and higher-value processing remain externalized, countries struggle to add value locally, limiting job creation, weakening political durability for transitions, and constraining broader economic upgrading.

Regulatory fragmentation further undermines industrial collaboration. Divergent standards and procurement requirements slow the formation of cross-border partnerships and make it harder for firms to scale regionally. Non-tariff barriers can be particularly restrictive. For example, technical clauses may limit the use, repair, or modification of imported technologies, even when those technologies have been deployed for decades, thereby reducing learning-by-doing and locking countries into vendor dependence. At the same time, competitive overlap in manufacturing ambitions particularly in sectors such as solar, batteries, and electric vehicles across the four countries raises the risk of parallel industrial policies that fragment markets rather than create complementary specialization. Without deliberate coordination on standards, component niches, and market design, industrial competition risks crowding out the development of resilient regional value chains.

Joint Technological Innovation and Knowledge Exchange

Technology and innovation cooperation faces institutional hurdles that are less about capability and more about connection and coordination. Joint research and development (R&D) remains limited. In practice, researchers often work on similar questions in parallel and lack consistent engagement across ecosystems. Existing funding models are also poorly aligned with deployment realities. Public R&D usually rewards laboratory results and academic publications, but provides far less support for piloting, demonstration, certification, and early-stage commercial deployments. Because these mid-stage steps require substantial capital and carry high performance risk, private capital is often reluctant to step in, creating a well-documented "Valley of Death," in what the Welding Institute describes as Technological Readiness Levels 4-7. As a result, promising ideas fail to become demonstrable, financeable, and scalable technologies. Technology transfer barriers further exacerbate the problem, as countries with ambitious renewable energy plans continue to depend on imported equipment, perpetuating structural dependence.

Human Capital and Just Transition Cooperation

While the just transition as a concept has received growing attention, practical cooperation frameworks remain underdeveloped. Countries face skill shortages across all levels technicians, installers, grid operators, project developers, and regulators — creating bottlenecks that delay projects, particularly in the case of distributed renewables, which require rapid workforce scaling across multiple localities. Training efforts often prioritize formal education pathways over hands-on, on-the-job skills, resulting in underinvestment in competencies that align with immediate deployment needs.

These gaps are further exacerbated by brain drain, as highly qualified researchers and professionals are drawn to better-funded ecosystems. More fundamentally, beyond questions of technology ownership, persistent capacity gaps remain in implementation and maintenance. Even when equipment is procured, long-term performance depends on local systems capable of operating, repairing, and upgrading technologies - capabilities that require sustained investment in people, institutions, and vocational infrastructure.

Energy Governance and Data Cooperation

Another key issue is that energy governance and data cooperation remain constrained by inconsistent standards and fragmented reporting methodologies. Limited transparency can deter investment, especially for smaller-scale or first-of-a-kind projects that depend on reliable baseline data to price risk accurately. Governance gaps also intersect with the physical realities of power systems. Grids across these countries were largely designed around coal and other thermal generation, leaving them less prepared to manage intermittency and uncertainty at high levels of renewable penetration. This legacy design increases integration costs, complicates system planning, and raises overall capital requirements.

Reliability challenges, such as unplanned power outages, carry both economic and social costs, disrupting industrial activity and disproportionately affecting vulnerable communities. Without stronger governance frameworks, improved data systems, and coordinated planning tools, energy transition risks become more expensive than necessary and less equitable than intended. Taken together, these governance, data, and grid-integration gaps underscore that the challenge is not ambition, but the coordination, implementation capacity, and bankable conditions required to translate ambition into delivery.

The following section turns from diagnosis to action, outlining practical pathways for IBSA+Indonesia to co-create solutions through shared roadmaps, targeted partnerships, and financeable implementation plans.

IV. FUTURE PATHWAYS FOR CO-CREATION

From diplomatic harmonization and coordinated climate finance strategies to strengthening clean energy supply chains and fostering regional technology hubs, the pathways outlined in this section reframe energy transitions as engines of growth, development, and coordination across IBSA+Indonesia. By investing in human capital, institutional capacity, and interoperable energy governance frameworks, the grouping can demonstrate that the Global South is not merely a recipient of solutions, but a co-architect of the global energy future. These pathways are informed by an intensive roundtable discussion convened in Cape Town in November 2025, where policymakers, practitioners, and experts examined concrete options for deepening cooperation across IBSA+Indonesia.

Diplomatic Harmonization and Strategic Alignment

The vulnerability of Global South energy transitions has been further exacerbated by external shocks and recent crises, including the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted supply chains for renewable technologies. Subsequent energy price volatility following Russia's invasion of Ukraine exposed the fragility of energy import-reliant economies, many of which are in the Global South. These experiences underscore the need for collaborative platforms that can pool resources and ensure that Global South priorities remain at the forefront of international dialogue. A core strategy for an IBSA+Indonesia energy transitions collective is to leverage the group's combined political, economic, and demographic weight to assert leadership and counter misleading or incomplete narratives.

Coordinated Positions

As future G20 presidencies unfold, sustained coordination among IBSA+Indonesia countries will be important to carry forward and build on the Global South energy transition priorities advanced during their respective G20 leadership cycles. Strengthening institutional, bilateral, and multilateral engagement — both within IBSA+Indonesia and with other Global South partners can help maintain continuity and reinforce shared objectives over the long term. Through constructive engagement and evidence-based dialogue, the grouping can also contribute to shaping balanced global narratives on energy transitions, including perspectives on risk, development, economic opportunity, and energy security, ensuring that transition pathways are understood as enablers of growth and resilience.

Shared Vision

To streamline coordination and avoid bureaucratic bottlenecks, the backbone of this effort should take the form of a light-touch coordination mechanism, such as a small secretariat or project management unit (PMU), with direct reporting lines to political leadership. Through this mechanism, a central shared vision document should be developed, outlining a clear work plan, priority areas, coordination touchpoints, and milestones. Each country should identify one or two thematic pillars that reflect domestic strengths and regional expertise, helping to organize representation, distribute workloads, and avoid duplication. Socio-economic dimensions — particularly equity and justice in energy transitions should remain central, as they continue to be underrepresented in global forums. Governments should also prioritize systematically engaging diplomatic corps in technical energy transition discussions, enabling them to advocate more effectively and support cross-border research and policy collaboration.

Diplomatic Calendar & Sequencing

An IBSA+Indonesia platform should identify concrete touchpoints within the global diplomatic calendar to review progress, align positions, and define future deliverables. Diplomatic convenings where energy transitions are a core agenda item — or a cross-cutting deliverable —offer natural opportunities for coordination and engagement. These include the Conference of the Parties (COP), G20 energy and finance working groups and ministerials, the Clean Energy Ministerial, the IRENA Assembly, BRICS summits, MDB annual meetings, and the Sustainable Energy for All Global Forum. In addition, major annual forums convened by organizations such as the World Economic Forum, Reuters, the Financial Times, and the Observer Research Foundation can further support the Global South energy transition agenda by hosting dedicated, issue-focused dialogues within their broader programming.

Climate Finance Mobilization

The challenge of scaling investment from approximately $250 billion in 2024 to over $1.3 trillion annually by 2030 across these countries is complex and multilayered. To meet this ambition, projects seeking to attract green capital must be both competitive and bankable. The main obstacles — high costs of capital, underdeveloped green investment markets, and persistent risk perceptions by external credit institutions — are systemic rather than project-specific. Bridging this gap therefore requires a comprehensive and coordinated approach that leverages collective strengths in financial innovation, domestic commitment, and regional cooperation.

Joint Project Pipelines

A robust and diversified pipeline of projects that can attract both public and private investors is essential for unlocking capital at scale. Building on regional strengths — such as solar in India, offshore wind and bioenergy in Brazil, battery storage in South Africa, and geothermal in Indonesia — projects can be bundled into larger, diversified investment packages that reduce risk and enable scale. The early launch of a limited number of high-impact projects can help demonstrate bankability, standardize risk assessments, and build investor confidence. Such coordinated investment platforms can also strengthen signaling around policy coherence and long-term commitment to emissions reduction. Multilateral development banks will be critical in this context, helping to manage project selection, signal credibility to capital markets, and absorb early-stage risks. South–South financial institutions, including the New Development Bank, can play a complementary role in supporting these efforts.

Addressing the Cost of Capital

Persistently high costs of capital in Global South countries remain a major constraint on clean energy investment. Risk assessments conducted by geographically distant credit rating agencies often rely on generalized assumptions, which can inflate perceived risk and undermine project bankability. IBSA+Indonesia countries could work toward establishing regional or context-sensitive credit assessment mechanisms that better reflect domestic economic fundamentals and policy commitments. At the same time, multilateral instruments, including political risk insurance, credit guarantees, and concessional finance, can further mitigate risk and help lower financing costs for priority projects.

Leveraging Domestic Public Capital

Mobilizing domestic public capital sends a strong signal to investors that countries are committed stakeholders in their own energy transitions. While national development banks across IBSA+Indonesia have increasingly integrated sustainability and green finance into their mandates, greater scale and earlier-stage risk participation will be necessary to crowd in private capital. Public sources such as pension funds can play a larger role by allocating a meaningful share of their portfolios to green investments, thereby linking domestic savings to sustainable growth. Sovereign wealth funds, such as Indonesia's Danantara, could also earmark dedicated windows for green investments across IBSA+Indonesia countries to strengthen regional supply chains. Similar reciprocal approaches could be explored by India, South Africa, and Brazil.

Supporting MSMES

Micro, small, and medium green enterprises (MSMEs) often face disproportionately high transaction costs, particularly for smaller scale projects. Yet these enterprises are critical to the long-term sustainability of clean energy ecosystems and form the backbone of a just and inclusive energy transition. Aggregating MSME projects into investable portfolios can significantly improve access to finance. In parallel, IBSA+Indonesia countries can provide targeted technical assistance and concessional finance to help reduce development costs, strengthen business capacity, and enable MSMEs to participate more fully in energy transition value chains.

Standards in Supply Chain and Industrial Cooperation

Strategic coordination across supply chains and standards can elevate IBSA+Indonesia from a coalition that advances diplomatic narratives on green transitions to a credible green industrial bloc one that is trusted as a supplier, manufacturer, and market shaper in global clean energy value chains. Achieving this shift will require overcoming persistent constraints, including regulatory fragmentation, weak logistics integration, and competitive overlap across renewable energy manufacturing.

Building a Clean-Tech Corridor

IBSA+Indonesia can advance industrial cooperation by establishing a clean-tech corridor that facilitates tariff reductions and streamlined trade for priority green technologies. The foundation of such a corridor lies in interoperable standards and taxonomies, including aligned green investment classifications. A shared taxonomy would enable cross-border financing, lower transaction costs, and reduce regulatory uncertainty for investors. Harmonized standards for renewable power generation, storage, and associated technologies would further support green public and private procurement, strengthening regional supply chains and enabling firms to scale across markets.

To reinforce credibility and transparency, IBSA+Indonesia should jointly develop a monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) platform that tracks supply-chain sustainability, emissions intensity, and compliance with agreed standards. Embedding the participation of MSMEs within this corridor will be essential to ensure that industrial gains are broadly distributed and aligned with just transition objectives.

Demand Creation and Market Stabilization

Early demand signals will be critical to accelerating industrial scale-up. Complementary policy tools, including contracts for differences, credit guarantees, and strategic public procurement, can help de-risk early investments, support domestic manufacturing, and attract international finance and technology partnerships. Coordinated demand-side measures across IBSA+Indonesia markets would reduce uncertainty for investors and manufacturers, enabling faster deployment and cost reductions.

Credible Certification and Aggregated Green Markets

To enhance global competitiveness, IBSA+Indonesia should collaborate on certification systems for responsibly sourced critical minerals and clean technology components. Such certification would strengthen the credibility of green products in international markets and respond to growing scrutiny over environmental and social standards. Building on this foundation, IBSA+Indonesia could support aggregated markets for green commodities by including green hydrogen, green steel, and batteries thus helping to mitigate market volatility, secure long-term offtake agreements, and anchor regional industrial ecosystems.

Technology and Knowledge Sharing Hubs

Deepening cooperation on technology and knowledge exchange is essential for translating IBSA+Indonesia’s energy transition ambitions into scalable and deployable solutions. Establishing integrated technology and knowledge-sharing hubs can enable systematic exchange of best practices, lessons learned, and operational insights across the four countries. To be effective, these hubs must be grounded in context-specific solutions, driven by local implementation needs, and anchored in lighthouse pilot projects rather than abstract research collaboration.

Sector-Focused Innovation Hubs

Technology and knowledge hubs should be organized around priority transition sectors where all four countries face shared challenges and where collective learning can accelerate deployment. These include smart grids, energy storage, green hydrogen, and digital energy systems. Joint pilot projects developed through these hubs can serve as demonstration cases — testing technical performance, regulatory readiness, and commercial viability under real-world conditions. By doing so, they can help signal bankability to investors and position IBSA+Indonesia as a source of credible, deployable solutions for global clean energy markets.

Bridging the Valley of Death

A priority function of the IBSA+Indonesia technology hubs should be to address the well-documented gap between research and commercialization — the previously discussed Valley of Death. Rather than restating the challenge, these hubs can operationalize solutions by pooling public funding for demonstration projects, aligning national pilot and testing programs, and jointly supporting certification, validation, and early-stage deployment. By coordinating these mid-stage interventions, IBSA+Indonesia can reduce duplication, lower development costs, and accelerate the progression of promising technologies into deployable and financeable solutions.

In parallel, the hubs should serve as platforms to identify and address non-tariff barriers that constrain technology cooperation and transfer, including restrictive licensing and usage clauses that limit adaptation, repair, or scaling. Harmonizing approaches to testing, certification, and interoperability would further enable cross-border deployment, localized innovation, and faster diffusion of clean energy technologies across the grouping.

Enabling Mobility, Networks, and Knowledge Repositories

People-to-people exchange is a critical enabler of sustained innovation cooperation. A practical step to strengthen collaboration is to ease visa and mobility barriers for researchers, engineers, technicians, and policymakers working on energy transition priorities. Facilitating short-term exchanges, fellowships, and joint placements would help build trusted professional networks and accelerate learning across ecosystems.

To ensure continuity and institutional memory, lessons from pilots, policy experiments, and implementation experiences should be systematically captured in a shared digital knowledge and data repository. Such a platform would support evidence-based decision-making, reduce transaction costs for new projects, and enable faster replication of successful models across IBSA+Indonesia and other Global South contexts.

Building Human and Institutional Capacity

Fragmented workforce development systems, inconsistent labor policies, and the absence of mutual recognition frameworks for green skills continue to constrain effective collaboration across IBSA+Indonesia. These gaps limit the seamless transfer of expertise, slow project execution, and weaken the ability to scale solutions identified in earlier sections. When addressed through deeper institutional collaboration, trust-building, and talent retention strategies, IBSA+Indonesia can transform its diverse workforce into a cohesive engine for innovation, delivery, and long-term execution.

Harmonized Standards for Green Skilling

The IBSA+Indonesia group should work toward the development of common standards for green skilling and certification, enabling mutual recognition of qualifications across borders. Public–private partnerships focused on hands-on, industry-led training — particularly in sectors such as solar installation, battery storage, grid operations, and EV infrastructure — can rapidly expand the pool of job-ready workers. Such approaches would help address immediate workforce shortages while strengthening local capacity and reducing reliance on external expertise.

Leveraging Institutional Knowledge Ecosystems

Beyond government-led initiatives, the private sector, think tanks, training institutions, and civil society organizations play a critical role in shaping skills ecosystems and informing policy choices. Establishing structured platforms for dialogue among these actors can ensure that workforce strategies reflect operational realities and emerging market needs, while avoiding overrepresentation of any single stakeholder perspective. Governments should actively leverage this institutional knowledge to guide workforce planning, curriculum development, and long-term sustainability of skilling initiatives.

Talent Retention and Mobility

Retaining skilled professionals remains a persistent challenge across much of the Global South. Targeted strategies, including people-to-people exchanges, joint research programs, dedicated funding mechanisms, and career pathways linked to domestic projects, can help channel talent toward local institutions and priority initiatives. Flexible and time-bound mobility arrangements, including streamlined visa regimes among IBSA+Indonesia countries, can facilitate short-term exchange and collaboration while reducing the risk of permanent talent loss.

Energy Data and Governance

Effective energy transitions depend not only on finance and technology, but on the quality, interoperability, and governance of energy data. Across IBSA+Indonesia, energy data is often collected, managed, and disclosed through separate ministries, utilities, regulators, and system operators. Fragmented standards and inconsistent reporting methodologies limit comparability, weaken planning, and complicate decision-making. For investors, system planners, and policymakers alike, the absence of reliable and comparable data raises uncertainty, increases perceived risk, and slows project development.

Interoperable Data Standards and Transparency

Establishing common and interoperable data standards for energy systems would significantly improve coordination across IBSA+Indonesia. Harmonized approaches to data collection, reporting, and disclosure covering generation, grids, storage, demand, and emissions — would enable more accurate benchmarking, facilitate cross-border cooperation, and reduce transaction costs for investors. Greater transparency would also strengthen market confidence, particularly for first-of-a-kind and smaller-scale projects that depend heavily on credible baseline data to price risk and secure financing.

Digital Tools, Al, and System Planning

Advanced digital tools, including artificial intelligence and analytics, can further enhance data usability by standardizing metrics, improving forecasting, and stress-testing renewable integration under different scenarios. Shared modeling platforms and digital dashboards could support joint planning, enable peer learning among system operators, and improve the resilience of power systems as renewable penetration increases. When embedded within governance frameworks, these tools can help translate data into actionable insights for policymakers, regulators, and utilities.

Cybersecurity, Resilience, and Trust

As energy systems become more digitalized and interconnected, cybersecurity and system resilience become central to energy governance. Common security protocols, coordinated risk assessments, and regular stress-testing exercises can help safeguard critical infrastructure and build trust in shared data systems. Embedding cybersecurity standards within data governance frameworks throughout IBSA+Indonesia will be essential to ensuring that greater transparency and digitalization do not introduce new vulnerabilities.

V. CONCLUSION

Moving beyond shared challenges and ambition, this report has focused on translating ambition into concrete, implementable pathways for collective action. An IBSA+Indonesia partnership offers more than coordination — it provides a platform through which the Global South can exercise leadership, shape rules, and align energy transitions with growth, industrialization, and development priorities.

By advancing coordinated diplomatic positioning, IBSA+Indonesia can speak with a unified voice in global forums and anchor continuity across international processes. Through collective action to address the high cost of capital via aligned financial architectures, interoperable standards, and credible investment pipelines the grouping can unlock scale and accelerate deployment. Empowering MSMEs, strengthening local skilling ecosystems, and retaining talent will ensure that the benefits of energy transitions are broad-based, durable, and just. At the same time, deeper institutional cooperation and interoperable energy data and governance systems will be essential to delivering transitions that are transparent, secure, and resilient.

Taken together, these steps define a shift from parallel leadership to deliberate co-creation. By institutionalizing cooperation around finance, technology, skills, supply chains, and data, IBSA+Indonesia can not only secure their own energy futures but also keep the Global South's development-centered energy transition agenda firmly at the forefront of global decision-making. In doing so, the grouping can help ensure that the next phase of the global energy transition is not only faster and cleaner, but more inclusive, competitive, and aligned with the aspirations of emerging economies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their sincere gratitude for the valuable contributions of participants in the workshops, “Mapping Clean Energy Commitments and Ambitions in IBSA + Indonesia,” held on June 11, 2025, in Washington, D.C., and “Shaping Pathways: Unlocking Solutions to Strengthen IBSA + Indonesia Leadership in the Clean Energy Transition,” held on November 24, 2025, in Cape Town, South Africa. The insights and perspectives shared during these multi-stakeholder dialogues, featuring experts and practitioners from across the IBSA countries and Indonesia, have significantly enriched the research and recommendations presented in this report. The authors would also like to thank Jeffrey D. Bean for his edits. This publication is a part of ORF America’s Energy and Climate Program. The views and analyses expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of ORF America, its affiliates, or partner institutions.

Cover photo courtesy iStockphoto user rparobe.

Note: Citations and references can be found in the PDF version of this paper available here.